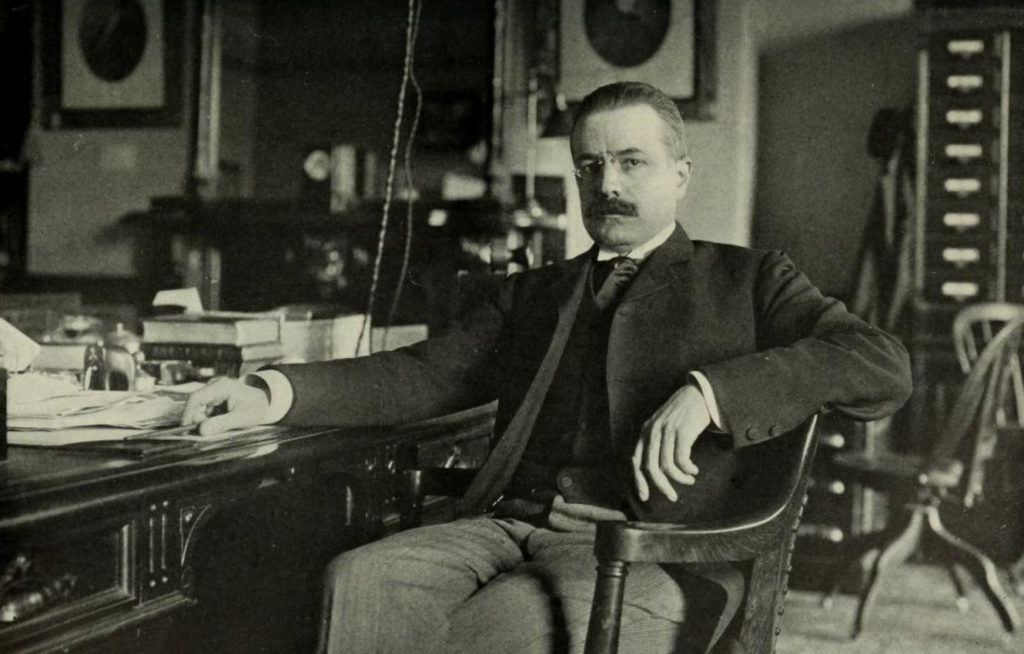

George B. Cortelyou, a mostly forgotten historical figure, authored one of the most important insider accounts of the final days before the Spanish-American War. His diary is one of the few contemporary descriptions of what was happening in the White House and what was going through President William McKinley’s mind before he requested authorization to use military force on April 11, 1898.

The Spanish-American War directly led to the annexation of the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, as well as governance of Cuba. The war was one of the most pivotal moments in U.S. foreign policy history, and its causes remain debated.

Cortelyou’s diary is archival gold. He wrote many diary entries in shorthand. Upon acquisition of the diary, the Library of Congress translated those entries and opened the diary to public research in 1967. One word from a critical diary entry on April 2, 1898 has never been translated — until now. My translation of that single word dispels two longstanding, powerful myths about the war that launched a sprawling overseas American empire.

First, it tells us that days before the request for authorization, war was not a foregone conclusion. Second, McKinley did not crumble under public pressure. To the contrary, the White House perceived the public as supportive of a policy of restraint. But more than anything, the translated word is a humbling reminder that history, much like life, is full of uncertainty. Until the very end, nobody knew what would happen next. Not even McKinley.

McKinley the Cipher

McKinley is a notoriously difficult president to understand. “One of the most enigmatic figures ever to occupy the White House,” historian Ernest May once wrote about him. “A man’s character usually emerges for the historian out of private letters. McKinley wrote none.” Historian Kristin Hoganson goes even further, writing that arguments of McKinley’s motives “ultimately must be based on conjecture.”

In truth, McKinley wrote some letters, but few relative to his predecessors and successors. He never kept a diary, he preferred to conduct much of his diplomacy in person (rather than via letter), and he was the first president to use the telephone to communicate with his executive departments and other policymakers, before anyone thought (or was required) to keep records of the calls. He was also assassinated in 1901, just six months into his second term, so he never wrote a memoir.

To understand McKinley and the decision-making environment in the White House, especially before the war, the papers of his advisers and confidants have proven to be critical resources. Few closer to the president left more clues than Cortelyou, who served as McKinley’s executive clerk at the time.

Cortelyou and the White House

Cortelyou entered the White House as a stenographer to President Grover Cleveland in 1895 and was soon promoted to executive clerk. He stayed on after McKinley’s election in 1896, despite the changing of the guard. Secretary to the President John Addison Porter was often absent due to illness or seeing to his own political ambitions. Porter’s administrative duties thus fell to Cortelyou in early 1898. Cortelyou spent a lot of time with the president, perhaps more than anyone else.

By the spring of 1898, Cortelyou had modernized the mail and communications system of the White House and was effectively acting as something in between a modern chief of staff, press secretary, and cabinet secretary. Because of this expanded portfolio, especially during the war, McKinley asked Congress to create a new position for Cortelyou, assistant secretary to the president, which Congress did in July 1898. Cortelyou would prove to be such an effective administrator that he would serve in the cabinet of McKinley’s fellow Republican, Theodore Roosevelt, in three separate positions, and even chaired Roosevelt’s 1904 presidential campaign as well as the Republican National Committee. Newspapers and elite Republicans even floated Cortelyou’s name as a potential presidential candidate in 1908.

He was not your typical clerk.

Cortelyou’s Diary and the Missing Word

After Cortelyou’s death in 1940, his son donated Cortelyou’s papers to the Library of Congress in 1942. Twenty-five years later, in 1967, the Library made them available for public research. Among these papers was Cortelyou’s diary.

A small handful of McKinley specialists reference Cortelyou and make use of his papers, but he remains grossly overlooked as a figure and as a source. In many major works on U.S. empire and the Spanish-American War by Eric Foner (volumes 1 and 2), Louis Pérez, Walter LaFeber, and Joseph Smith, for instance, Cortelyou is completely missing from the text. John Offner’s multi-archival 1992 classic mentions Cortelyou on just two pages — Hoganson’s, on just one.

Cortelyou wrote many of his diary notes in shorthand, specifically in the Pitman system (more specifically, in the Munson “dialect” of Pitman). Shorthand is a written system of English that uses abbreviated symbols to represent sounds. It was commonly used by stenographers, journalists, secretaries, and anyone else who wanted to scribble notes quickly. Woodrow Wilson was the last U.S. president who knew and took notes in shorthand. Cortelyou did not write shorthand diary notes every day, and, in the four weeks before the war, he mostly sketched brief thoughts on the crisis in Cuba and the emotional toll this was taking on McKinley.

Many entries deserve special mention, but the April 2, 1898 entry is particularly fascinating. First, it is one of a handful of entries after the Naval Board of Inquiry’s report on the USS Maine disaster was sent to Congress on March 28, but before McKinley’s request for the authorization to use force on April 11. The USS Maine tragically sank from a mysterious explosion while anchored in Havana harbor earlier that year on Feb. 15, killing 266 Americans. The USS Maine disaster increased tensions between the United States and Spain and contributed to a sense of uneasiness. But it neither made war inevitable nor precipitated it, as many mistakenly believe. McKinley — and Secretary of the Navy John D. Long — did not want war and never suspected Spain was to blame.

Consider this story: Alfred Mahan, the preeminent American naval strategist of the era, checked in with the Navy Department after the sinking of the USS Maine. He had planned on a seven-month European holiday with his family and asked whether he should cancel those plans in light of the incident. The department said no. Mahan and his family left in late March for Naples. Bizarre timing to send a senior naval adviser away if war was really believed to be on the near horizon.

Cortelyou’s diary entry on Apr. 2, 1898 captures the thinking in the White House in the critical few days after McKinley officially learned from the report that Spain was not responsible for the USS Maine attack but before he ultimately decided on war. After the report’s release, McKinley still faced some pressure from Congress to pursue war. Even though the report absolved Spain, it concluded that the explosion was externally caused, stoking suspicion of foul play. (It has since been established the explosion was internally caused and accidental). Despite growing pressure in Congress, key allies in the House of Representatives and Senate continued to support McKinley’s position of restraint, including Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed.

Still, McKinley felt the situation in Cuba was unsustainable. Spain’s brutal policies to suppress the Cuban independence movement since 1895 had caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Cubans. So much destruction and disorder so close to America’s shores created a sense of insecurity in McKinley’s mind. He knew that the United States had the capacity to do something about it, but he wanted war to be the last resort. McKinley continued to search for peaceful alternatives, but Spain would not agree to an armistice with Cuban rebels. Finally, on April 11, having exhausted all diplomatic avenues, including a mediation attempt by Pope Leo XIII, McKinley requested authorization to use military force. Congress granted it.

In addition to the timing, this diary entry is also important because it offers an assessment of public opinion. One of the longest-running narratives about the Spanish-American War is that sensationalist newspapers like the New York World and New York Journal whipped the public into a frothy war frenzy, and this pushed McKinley to war.

This explanation for war has been overstated ever since. It is a powerful myth that will not die. David Trask, for instance, in his authoritative work on the Spanish-American War, writes that “the people, acting out powerful irrational impulses, dictated the decision of April, 1898.” Some historians, like W. Joseph Campbell, have offered compelling correctives to this. Yet, it lives on, even among the most talented historians of our era — like Jill Lepore, who repeats a debunked quote attributed to William Randolph Hearst (“You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war”) and broadly emphasizes the yellow press and public opinion in her widely celebrated history of the United States.

In the absence of polling, it is quite difficult to measure what the public actually believed. Analysis of newspapers of the time (beyond the sensationalist “yellow press”) offers some measurement of public opinion, but there were probably just as many newspapers that formally aligned with the president and the Republican Party as those that were Democratic (back then, media companies proudly affiliated with political parties). Finding newspaper articles in favor of war is rather meaningless, given the number that also advocated restraint.

But, for the purposes of understanding the president’s decision, what matters more than what the public believed is what the White House believed the public believed. Cortelyou’s April 2 diary entry delivers the last insider assessment of public opinion before McKinley requested Congressional authorization to use force. That segment of the diary reads:

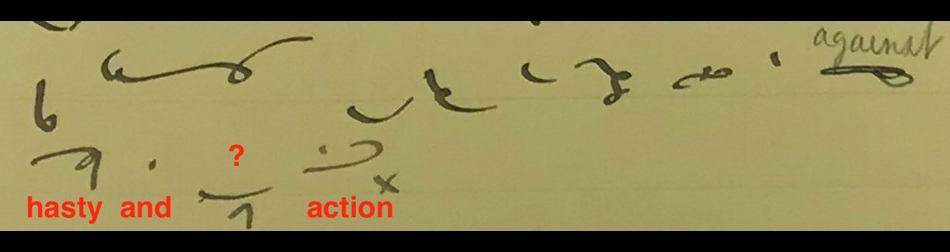

The mail continues as much as ever, and with the exception of a few letters, from irresponsible sources and from cranks it is unanimously in favor of the President’s course and against hasty and ____ action.

The “____” is a word that was never translated from shorthand by the Library of Congress, which supplied typewritten transcripts of Cortelyou’s diary entries. Based on my study of Munson’s system of shorthand and consultation with a Pitman translator (a rare gem), I believe that word is “new.” See for yourself:

Source: Box 52, George B. Cortelyou Papers, Library of Congress. Red text added. The word “against” was likely written by the Library of Congress translator.

And now the Munson shorthand symbol for the word “new”:

Source: C. Van Sant and Elizabeth Van Sant, Manual of Munson Shorthand (Chicago: J. A. Lyons & Company, c1913), 127.

The symbol for “new” is not a perfect fit. In particular, the caret underneath the swoop is differently placed, and the diary entry also contains a small loop (called an “s-circle”) at the beginning. It may have been for these reasons that the translator did not transcribe the word as “new.”

The s-circle at the beginning signifies a word that starts with an “s” sound. The swoop is called a “curved horizontal stem,” which is only used to represent the letter N (or, if written in bold, for the ending “-ng”). That the curved stem appears below the line, with an acute caret, implies Cortelyou meant to represent the diphthong “ew.” Typically, however, the caret is attached at the end of the stem, not closer to the middle, which does not make any sense (nor signify a different word). Accepting that the caret was misplaced, the word still translates to “snew,” which still does not make any sense. Perhaps meeting this confusion, the translator skipped this word.

Yet, for someone who was writing after 14-hour, sometimes 16-hour, days in the office, at a moment of extreme stress, Cortelyou was probably scribbling these notes quickly. The caret placement is almost assuredly a mistake, since putting it in the middle of the stem does not add different information. As for the s-circle, it is far more tentative and minor than the s-circles that appear elsewhere in the entry itself. Words earlier in the sentence betray far larger and more deliberate s-circles. What is more likely is that Cortelyou hesitated before writing this word — as many people do when writing — perhaps starting it with an unthinking mark, writing the word “new,” and never looking back.

With this perspective, Cortelyou’s line about the mail translates to: “…unanimously in favor of the President’s course and against hasty and new action.”

This is a significant statement. First, it indicates that the White House judged public opinion based on the letters it received in the mail, not merely on newspaper articles. Historians of the era often overlook received letters as a resource, cherry-picking newspaper articles instead.

Second, it points to a perception that the public was supportive of the president’s policy, which had been a policy of restraint, until — of course — he decided ultimately for war. It also indicates that the public was not as frenetic as some scholars have led us to believe. In an ironic twist, Hoganson’s single reference of Cortelyou mischaracterizes his assessment of constituent mail, as she argues that Cortelyou reported it was increasingly supportive of war. That would be only true if you stopped reading his diary on March 29. As we see here, on April 2, Cortelyou feels quite differently. He doubles down on this assessment two weeks later on April 16, after McKinley requests the authorization to use force (but before the formal declaration of war).

In particular, the word “new” adds a fascinating dimension to the final days before the war. Given that the war happened, it is tempting to characterize the lead-up as exactly that: a lead-up. A build-up. A slide toward war. But history, as my Ph.D. adviser, Fredrik Logevall, often counseled, should be told forwards, not backwards. Our knowledge that the war took place skews how we judge the probability of conflict in the days preceding it and thus skews how we explain it (something Richard Zeckhauser and I call “explanation bias,” different from “hindsight bias”).

Offner’s assessment of February 1898 captures this very trap in writing history. “Time was running out,” he writes, after the USS Maine attack. Running out for what? We know, now in hindsight, that war came weeks later. But people at the time did not know that. Why would they have had a sense, in February, that “time was running out”?

In short, the word “new” reveals the uncertainty of the contemporary moment. Uncertainty is often forgotten in the retelling of history. Narrative arcs can lead readers to believe that events and decisions followed a probable pathway. But we should not confuse probability with plausibility. By knowing what did happen, we inflate the probability of a potential future that decision-makers faced at the time. Cortelyou was writing that the White House believed the public viewed an act of violence or a declaration of war as “new,” not as the next logical step in the crisis.

What is more is that Cortelyou implies that this was also the position of the president. Indeed, the final few days before McKinley’s request for the authorization of force witnessed a flurry of final attempts to resolve the crisis diplomatically and peacefully. These attempts failed. But their failure should not lead anyone to believe that war between Spain and the United States was inevitable.

Dr. Aroop Mukharji is a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Strategic Studies at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. He received his Ph.D. in public policy from the Harvard Kennedy School, where he is an associate in the Applied History Project at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Follow him on Twitter at @aroopmukharji

Image: WikiCommons (Portrait of George B. Cortelyou)

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Library of Congress made Cortelyou’s papers available for public research fifteen years after Cortelyou’s son donated them to the library. The papers were made available twenty-five years later.