Japanese Nuclear Policy After Hiroshima, After Abe, and After Nov. 3

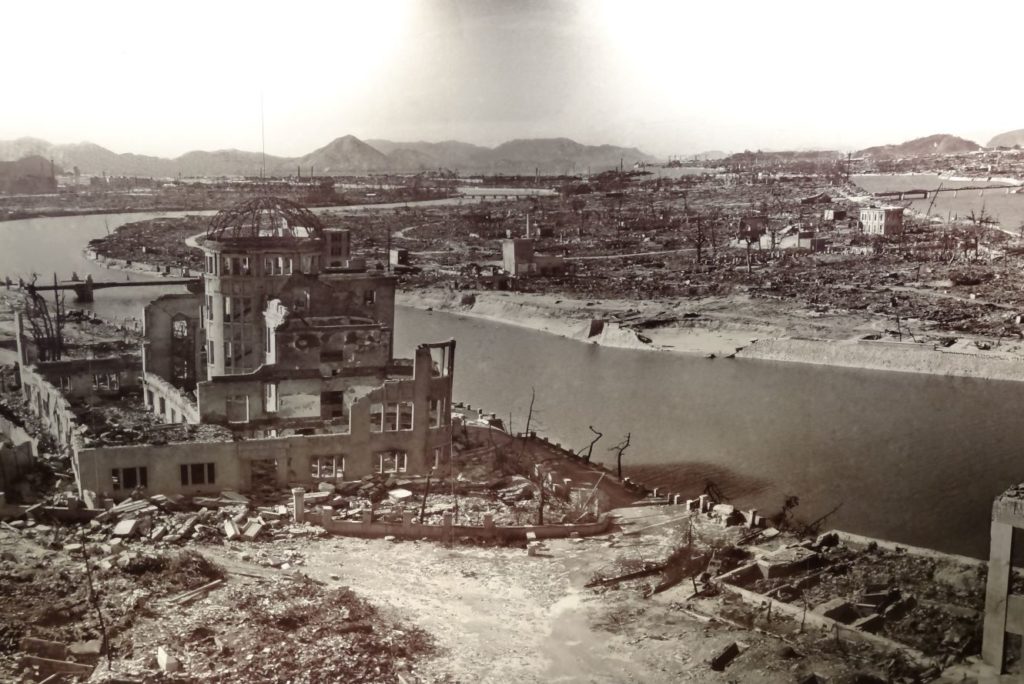

On the morning of Aug. 6, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan delivered a cautious statement in front of the Hibakushas, the victims of the atomic bombs dropped on two major Japanese cities. One of the two cities, Hiroshima, marked the 75th anniversary of the nuclear assault that day. A diminished number of participants, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, carefully listened to Abe’s message as it echoed over the solemn ceremony in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

“As the only country to have experienced the horror of nuclear devastation in war, Japan has the unceasing mission of advancing steadily, step by step, the efforts of the international community towards realizing ‘a world free of nuclear weapons,’” Abe said.

During the remarks, which I covered from about 100 meters away, Abe didn’t forget to mention Japan’s unwavering commitment to the Three Non-Nuclear Principles (not possessing, not producing, and not permitting the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japanese territories). This hard-and-fast national policy was officially declared and formulated in the late 1960s by Abe’s great-uncle, then-Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, who was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1974, mainly thanks to this nonnuclear declaratory policy.

However, contrary to the strong wish of the Hibakushas and their peace-loving supporters, in the roughly eight years Japan has been governed by Abe — one of the most conservative and promilitary prime ministers in modern Japanese history — the country has increasingly and more unequivocally relied on the nuclear umbrella provided by its key ally, the United States.

The main reasons for this trend are two geopolitical factors. The first is the aggressive military buildup by China, which adamantly insists on its territorial sovereignty over the Japanese Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. The second is North Korea’s expanding nuclear and missile program, which U.S. President Donald Trump has so far failed to reverse through his oft-trumpeted, if incomplete, bilateral summit process.

One fact of the matter is that the nuclear reliance policy driven by the Abe administration has deepened the dilemma and ambivalence of Japan, the majority of whose people oppose nuclear arsenals in general and want their government to sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons adopted at the United Nations in 2017.

The public sentiment on this point was eloquently vindicated by another statement during the same ceremony on Aug. 6. From the same podium Abe had used just several minutes before, the governor of Hiroshima, Hidehiko Yuzaki, announced in an emphatic manner, “Nuclear deterrence is no more than a manmade myth, which loses its validity once enough of us stop believing in it.”

Securing Trump’s ‘Nuclear Commitment’

In the past few years, the political scene most symbolic of Japan’s increased dependence on the U.S. nuclear umbrella was seen on Feb. 10, 2017, when Abe and Trump issued the U.S.-Japan Joint Statement.

It says, “The unshakable U.S.-Japan Alliance is the cornerstone of peace, prosperity, and freedom in the Asia-Pacific region. The U.S. commitment to defend Japan through the full range of U.S. military capabilities, both nuclear and conventional, is unwavering.”

One of the top agenda items for Abe and Trump’s first official summit meeting in 2017 was North Korea. At the exact same time as the two leaders were meeting at Mar-a-Lago, North Korea launched a missile believed to be a modified version of the intermediate-range ballistic missile Musudan. The meeting was overshadowed by the nuclear threat posed by the country, which had accelerated a series of missile tests since 2016.

Against this backdrop, Abe and Trump announced their joint statement. It was the second time in the history of Japan that the country’s top leader asked the U.S. president to guarantee Japanese national security through U.S. nuclear arsenals, if necessary, on the public record.

The first occasion was on Aug. 6, 1975, when then-Prime Minister Takeo Miki and U.S. President Gerald Ford published the U.S.-Japan Joint Announcement to the Press, which confirmed that “the U.S. nuclear deterrent is an important contributor to the security of Japan.”

Japanese policymakers had reason to be concerned about Trump’s commitment to the security alliance, especially amid increasing tensions with North Korea. During the election campaign in 2016, Trump said, “If we’re attacked, Japan doesn’t have to do anything. They can sit home and watch Sony television, OK?”

Trump was the first U.S. president to criticize the U.S.-Japanese security alliance. Under its peaceful constitution drafted by the U.S. occupation power almost 75 years ago, Japan has been prohibited from directly getting involved in U.S. military combat operations outside Japanese territories.

In this context, security policy elites of the Abe administration tried their best to reconfirm the nuclear deterrence commitment made by a series of U.S. administrations at a very early stage of the Trump presidency. This effort bore fruit when Trump himself engaged with the joint statement, which reaffirmed the credibility and effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

While it was very difficult to know to what extent Trump understood what the joint statement meant in terms of the U.S. deterrence commitment, Japanese security officials must have nevertheless been relieved by this significant statement, which they could have assumed would strengthen a “nuclear bond” between Japan and the United States.

‘High Appreciation’ of Trump’s Nuclear Posture Review

Almost a year after the first Abe-Trump summit took place, the government of Japan tried another measure to reaffirm the U.S. nuclear commitment to protect Japan.

On Feb. 3, 2018, then-Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono released a succinct statement with a clear signal to the United States. It said,

The U.S. Department of Defense released its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) on Friday, February 2. Japan highly appreciates the latest NPR which clearly articulates the U.S. resolve to ensure the effectiveness of its deterrence and its commitment to providing extended deterrence to its allies including Japan, in light of the international security environment which has been rapidly worsened since the release of the previous 2010 NPR, in particular, by continued development of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs.

Kono’s statement was released just one day after the Trump administration made public its Nuclear Posture Review. The Japanese intention was very simple and obvious. Facing a dire situation with repeated missile launches by North Korea and China’s rapidly modernizing military, the Abe administration tried to reaffirm to Washington that Japanese security is highly dependent on U.S. nuclear extended deterrence by demonstrating full support of Trump’s nuclear policy.

However, this Nuclear Posture Review includes several controversial points: It suggests introducing low-yield nuclear weapons into Navy strategic submarines, does not exclude a nuclear retaliatory option against adversaries’ strategic cyber attack, and objects to Senate ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.

The last point especially is politically puzzling for the government of Japan, which has been an avid and long-term advocate for early entry into force of the test-ban treaty. Under the Obama administration, the United States promoted the same goal in tandem with Japan on this important disarmament agenda, but Trump reversed the policy discourse.

Recently I had a chance to talk with Kono, who also served as Abe’s last defense minister, on this specific topic and I asked him why he gave a highly appreciative statement about the Trump Nuclear Posture Review when it totally rejects the possibility of U.S. ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. He explained that he had tried to persuade then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to change the Trump administration’s position on the treaty by using the leverage of an ally that supports the Trump administration’s nuclear policy.

As far as I know, Japan is the first nation to express clear and full support of Trump’s Nuclear Posture Review. Despite well-considered diplomatic calculation made by those in Japanese foreign policy circles seeking to induce the Trump administration to be more positive on the nuclear disarmament agenda, it seems Kono could not make it happen.

This anecdote reminds us of the ambivalent nature of Japanese nuclear policy. Kono might have assumed strengthening the “nuclear bond” with the United States would definitely increase Japanese political influence on U.S. policymaking on the nuclear disarmament agenda, upon which Japan has focused keenly. However, the reality he faced was bleak.

Cold Shoulder to Nuclear Ban

At the 75-year anniversary ceremonies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, both city’s mayors made a strenuous appeal in one voice to Abe to sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. However, the Abe administration has been giving the cold shoulder to this nuclear ban treaty and its most ardent supporters, the Hibakushas. (In Nagasaki, I was privileged to take a seat in the front row of the ceremony, where I could clearly observe Abe carefully listening to what Mayor Tomihisa Taue announced in the peace declaration. But Abe did not mention the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons at all in either Nagasaki or Hiroshima.)

In 2017, the Abe administration did not participate in the multilateral negotiation process for adopting the nuclear ban treaty at the United Nations in spite of broad support for the treaty among the Japanese public. According to a public opinion poll conducted by Kyodo News in November 2016, 71.1 percent of the Japanese public believed Japan should participate in the treaty negotiation.

Japanese policymakers have suggested that the Abe administration decided in 2017 that the treaty would undermine Japan’s security environment.

The deep, serious division between the nuclear weapon states opposing the treaty and the nonnuclear weapon states supporting it was another factor. However, the most fundamental reason Tokyo continues to reject the nuclear ban treaty is Tokyo’s dependence on the nuclear umbrella provided by the United States.

Japanese officials may have feared that supporting the treaty would hurt the U.S.-Japanese “nuclear bond” that was reaffirmed by the joint statement announced by Abe and Trump in February 2017, which they saw as securing Trump’s nuclear commitment to Abe.

Abe and his security policy elites must have expected strong backlash from Japan’s antinuclear public on their decision not to participate in the treaty negotiations. Nevertheless, they made an unambiguous judgment that the bilateral security relationship with the United States, the sole guarantor of the nuclear umbrella for Japan, should be prioritized over participation in the treaty.

This episode sheds light on both the coherence and the ambivalence of Japanese nuclear policy. It also illuminates another reality: Japan’s deepening dilemma, caught as it is between a still strongly antinuclear public and its “nuclear gung-ho” ally.

What Will Be Next?

Japanese security officials are now starting to think about what a Biden administration’s nuclear policy would look like.

Just four years ago, after his historic first visit to Hiroshima as sitting U.S. president, Barack Obama gave serious thought to a nuclear “no-first-use” policy. However, this policy initiative failed as Japan and other allies opposed it for the same reasons Japan did not participate in negotiations on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons — so as not to diminish the nuclear umbrella provided by the United States in any way.

Needless to say, Biden was vice president under the administration that made the last push for no first use. Biden also left an important message to the world on behalf of Obama at the very end of his term. On Jan. 11, 2017, at the Carnegie Endowment in Washington, he stated his belief that the United States could now adopt no first use, saying, “Given our nonnuclear capacities and the nature of today’s threats, it’s hard to envision a plausible scenario in which the first use of nuclear weapons by the United States would be necessary or would make sense.”

In an article for Foreign Affairs early this year, Biden made the same assertion: “As I said in 2017, I believe that the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal should be deterring — and, if necessary, retaliating against — a nuclear attack. As president, I will work to put that belief into practice, in consultation with the U.S. military and U.S. allies.”

Of course, the “U.S. allies” he mentioned include Japan. After Nov. 3, what will be next for Japan’s ambivalent nuclear policy? Even after Abe steps down, we will not see any major change as long as his security-conscious successors, including the next prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, stay in power.

Masakatsu Ota is a senior/editorial writer with Kyodo News and visiting professor of Waseda and Nagasaki Universities. He is also a regular commentator for TV Asahi’s Hodo Station, one of the most popular news programs in Japan.

Image: Jeff and Neda Fields