“Predictions are hard, especially about the future.”

– Yogi Berra

“The global slowdown that began in early 2018 is nearing an end, according to Goldman Sachs Research economists, who forecast 3.4 percent global GDP growth in 2020. The modest increase from 2019’s expected growth of 3.1 percent will be driven by easier financial conditions, a US-China trade détente, and reduced Brexit uncertainty.”

– Goldman Sachs, Global Economic Outlook 2020: A Break in the Clouds, Nov. 25, 2019

Forecasting is an imperfect science. It is subject to low probability, high impact events such as this year’s COVID-19 breakout. More fundamentally, forecasters face problems stemming from the paradox that increased subject matter expertise is not correlated with accuracy in predictions. U.S. defense analysts must also face a rapidly shifting macroeconomic environment, wherein domestic politics conflict with rising international competition from Russia and China.

Stakeholders from Congress to industry to advocacy organizations all have a significant interest in understanding both the scope and direction of the Department of Defense’s budget. At over $750 billion, the U.S. defense budget is the largest in the world and funds activities ranging from air strikes to cutting-edge technology development and health research. Even minor shifts in spending growth over time would redirect tens of billions of dollars over a ten-year budget.

Defense budget analysts should consider a range of scenarios rather than working out a single most likely option. By forcing consideration of multiple potential outcomes, analysts can both hedge against some of the hazards caused by their own expertise and identify risks and opportunities that may arise as various conditions change.

Methods for Forecasting Defense Budgets

“Consensus is not always good; disagreement not always bad. If you do happen to agree, don’t take that agreement — in itself — as proof that you are right. Never stop doubting.”

– Philip Tetlock, “Superforecasting”

The field of forecasting has undergone a renaissance in the past two decades. The emergence of big data and the use of more structured forecasting reviews have opened up resources to forecasters and held up a mirror to the accuracy of many practitioners. The general consensus is that forecasting is a field with unrealized potential — combining the availability of new data sources with improved practices in how analysts approach answering questions.

Fundamentally, the biggest problem in forecasting is that the greater the expertise one develops in a given field, the more likely one is to develop strong priors as to the conditions driving the market or budget in question. These priors then make it difficult for analysts to take a neutral view on what is likely to happen next. A useful hedge against this is to work to ensure that a wider range of viewpoints are considered when forecasting, both in terms of which stakeholders are involved and which scenarios are considered. Beyond that, forecasters should strive to think probabilistically, be humble, and have a generally open mind.

As domestic and geopolitical conditions continue to rapidly evolve, it will become even more important for defense analysts to expand their window of possible outcomes and bring more rigor to the forecasting process.

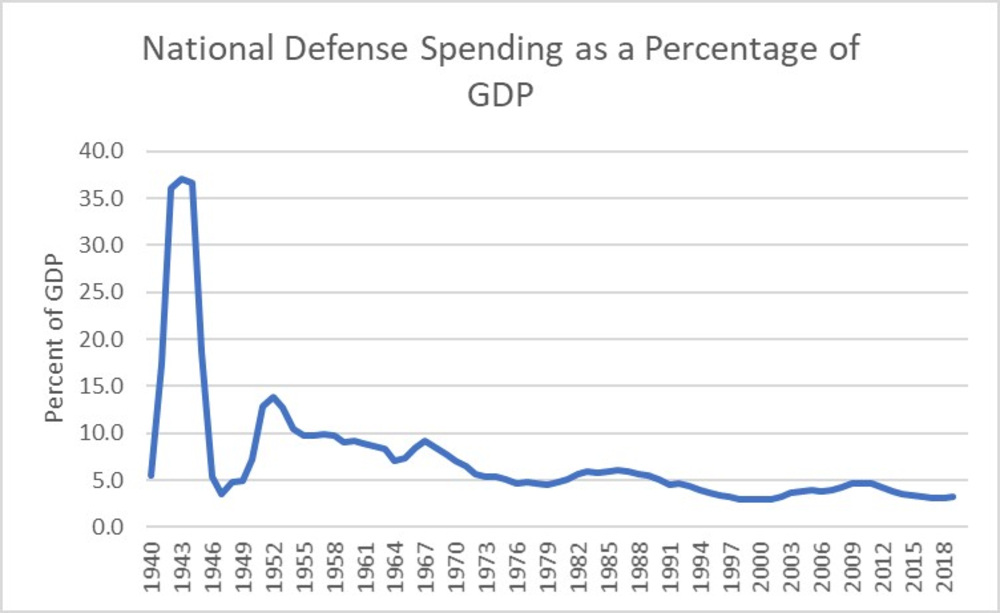

One note on methodology — in most of this article, defense spending will be discussed as a percentage of GDP rather than in real or nominal dollar terms. There are a few reasons for this; it’s easier to perform comparisons of the economic burden of defense spending over time and allows for easier comparison across countries. As noted in this very helpful War on the Rocks article, understanding defense spending in the context of the local economy provides a better perspective than standardizing into dollar values.

The End of a 30-Year Pause

The geopolitical realities facing the Department of Defense have begun to shift rapidly in the past decade. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has been the single great power operating on the world stage. As a result, the United States has been able to maintain its dominant military position while limiting defense expenditures.

Since 1990, American spending on defense has generally been fairly predictable; ranging between 3 percent and 5 percent of GDP, with an average of 3.8 percent during that time period. This level of military spending has been fairly modest by historical standards. By comparison, the lowest level of defense spending as a percentage of GDP during the Cold War was 4.8 percent.

Figure 1: Historic U.S. Defense Spending

Source: Graph generated by author with data from the Office of Management and Budget

The rise of China and the return of a revanchist Russia have signaled an end to this period of U.S. military dominance. China is on pace to become the world’s largest economy (based on Purchase Power parity) in 2020 and potentially pass the United States in aggregate GDP by 2030. Its military resources have also grown explosively, with defense spending increasing rapidly from less than $60 billion in 2008 to almost $240 billion in 2018. Beyond rising budgetary commitments to defense, China benefits from its own productive and low-cost industries to produce military ships at a rate that rivals, and in some cases surpasses, the United States.

While Russia lacks the vast and growing resources of China, it has amplified its influence under President Vladimir Putin by taking risks and combining traditional military power with non-traditional tactics. Military invasions of Georgia and Ukraine in 2008 and 2014, respectively, provide clear evidence of Russia’s willingness to risk global sanctions in service of geopolitical goals. Similarly, its intervention to protect its client regime in Syria represents another successful move to maintain control in the teeth of Western opposition. Moscow’s willingness to engage in clear influence campaigns in Western elections, most clearly in the United States presidential election and the Brexit referendum in 2016, highlights the global reach of Russian power.

Beyond the question of whether additional expenditures represent the best path for dealing with an increasingly unsettled globe, the more pressing issue is likely to be whether U.S. domestic politics allow such a response. While geopolitical pressures may point to a world where spending on defense and security in the United States returns to higher historical norms, it will still remain for Congress and the executive branch to determine how best to balance defense spending with rising entitlement costs and revenues limited by seemingly endless rounds of tax cuts. Looming above all of this is the $23 trillion the federal government owes in debt.

Guns and Butter?

At the same time that America’s strategic position is becoming precarious, its domestic politics have shifted rapidly in a way that makes the defense budget more vulnerable to pressure. Functionally, this is from two major factors; first, the federal debt held by the public has exploded from 41 percent of GDP in 1990 to 78 percent in 2019, raising the risk of higher interest rates. Second, the composition of government spending has shifted such that popular entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare are competing with the Defense Department for a potentially dwindling pool of federal dollars. This exposes defense spending to cuts under any austerity program that it might have been able to avoid in earlier times.

While current economic forecasts are in a state of flux due to the global impact of COVID-19, it is mainly a question of how much damage will be done to the economy and how much debt the government will incur in attempting to mitigate those losses. This will be on top of the growth in deficits from the end of the Obama administration and the first few years of the Trump administration. In the past five years, annual budget deficits have been growing rather than decreasing, as one would expect during a period of sustained economic growth, rising from 2.8 percent of GDP in 2014 to 4.2 percent of GDP last year. More ominously, even without a future recession, the Congressional Budget Office expects those deficits to continue growing — rising to 8.7 percent of GDP by 2049. While defense spending has also grown during this period, the vast majority of the growth in the deficit is due to increases in mandatory spending (mostly on Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare) and reductions in revenues. Federal revenues have declined as a share of GDP every year since 2015 and are forecast to remain below 18 percent of GDP through 2027. These large and growing deficits may eventually force Congress and the White House to adopt austerity measures. Due to the popularity of social programs, the Defense Department and other non-defense discretionary programs could be asked to bear the brunt of any cuts.

Defense hawks should not assume that there will be political will to slash social spending to protect defense. In a poll from April 2019, Pew Research Center reported that 48 percent of Americans wanted to increase spending on Social Security and 55 percent wanted to increase spending on Medicare, with only 8 percent advocating reductions to these programs. Conversely, only 40 percent advocated increasing defense spending with 23 percent recommending reductions. While spending levels have continued to rise despite the debt in the past decade, there remains the possibility that interest rates could rise in response to higher debt levels, which could force Congress and the White House to adopt austerity. Should that occur, strong political support for mandatory spending in the face of austerity would add further pressure to defense spending levels.

Plans are Worthless, but Planning is Everything

In the face of these conflicting trends, analysts should begin by acknowledging that the likelihood of any one forecast capturing the twists and turns of the next ten or even the next five years will be very small. Instead, analysts should start by trying to sketch out a wider range of reasonable outcomes based on historical analysis of the budget and a review of how similar situations may have played out elsewhere. The real value of scenario review lies not in having a range of lines to look at, but in thinking through which behaviors customers might exhibit in these varying scenarios and which operating conditions might be present.

With respect to defense spending, there should be a high case featuring a rising budget in a new Cold War environment, a status quo forecast, and an austerity case where the department must operate under reduced budgets. Each of these would provide useful information; a sense of what events would signal movement towards a given end-state, how different agencies might choose to prioritize resources given varying levels of budget allocation, and potential threats to a given program or contractor portfolio. Below is a very generic version of what a potential range of outcomes could look like.

High Forecast

A high forecast for defense spending would take place in a world where the geopolitical risks associated with China’s rise becomes too high for policymakers in both parties to ignore. This could be prompted through any number of occurrences — action against the independence protests in Hong Kong, growing economic tensions, or saber-rattling by China against Taiwan. In such a world, the United States makes a serious commitment to respond and then seeks to match the growing Chinese defense budget. This move might put pressure on the federal budget, but one can envision scenarios where an administration is willing to run the risk of inflation in order to make sure America remains capable of countering any potential threat.

Figure 1: Spending scenarios with high (blue), status quo (yellow), and austerity (red) forecasts. Soure: Generated by the author.

Soure: Generated by the author.

Status Quo Forecast

A status quo forecast would be one where the push and pull of geopolitics and domestic budgetary pressures effectively offset and spending continues to grow at or around inflation. This allows the Pentagon to somewhat abide by the National Defense Strategy, but it will be held back by lack of funds from fully committing to maintaining dominance in great-power competition.

Austerity Forecast

An austerity forecast would be one where, for either economic or political reasons, U.S. policy makers enact restrictions on spending growth. This could take place due to the budgetary and economic impact of COVID-19, rising interest rates should markets decide to stop treating U.S. debt as a safe haven, or other unforeseen factors. In this scenario, Congress would then be forced to take steps to reduce budget deficits in order to avoid seeing servicing the debt take up a growing share of the budget. This was the motivation behind the deficit reduction legislation that was adopted in the 1980s and 1990s. Alternately, a political dispute could lead to defense spending being cut, in a manner similar to the 2011 Budget Control Act. In either case, the result would likely be a near-term reduction in the budget followed by growth below inflation levels for a prolonged period.

Conclusion

In a period of growing uncertainty when the budget environment is beset with seemingly conflicting trends, analysts will need to take advantage of evolving best practices to forecast properly. Constructing a series of scenarios that allows analysts to think through the potential outcomes and effects of different budget environments creates a hedge against ignoring potential risks, and encourages analysts to avoid falling victim to their own assumptions.

Too often planning involves simply comparing cumulative average growth rates rather than seeking to understand the environmental and technological factors driving markets. Engaging in a more in-depth discussion of not just what spending levels may look like, but also the signals and actions that might accompany them, will give decision makers a better sense of how to respond to changing conditions. As the old saying goes, “plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” Decision-makers and analysts who engage in a rigorous review of potential future scenarios will be far better positioned to mitigate risks, and take advantage of opportunities that the shifting fiscal environment of the next ten years will present.

Matt Vallone is the Director of Research & Analysis at Avascent. He leads a team of defense and space-focused analysts in producing research products and data analysis. Prior to working at Avascent, he worked as the Legislative Director for Congresswoman Carol Shea-Porter in the House of Representatives. He holds a Master’s in security policy studies from the Elliott School at George Washington University and an M.B.A. from the Whittemore School of Business and Economics at the University of New Hampshire.

Image: Defense Department (Photo by Lisa Ferdinando)