Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a series on digital authoritarianism. The introductory essay can be found here. The concept for the series emerged from a policy workshop hosted by Bridging the Gap and the Center for New American Security.

Last year, the Wall Street Journal and AP broke stories about how Chinese technicians from Huawei were working directly with government security forces in Uganda and Serbia to install advanced facial recognition cameras for surveillance purposes. Both countries have spotty human rights records. In Uganda, longtime ruler Yoweri Museveni faces upcoming elections in 2021 and is laying a repressive groundwork to intimidate would-be political opponents and suppress opposition voters. Similarly, Serbia under the ruling Serbian Progressive Party has increasingly moved in an illiberal direction. Both governments have strong incentives to use digital tools to counter their opponents and ensure their political survival. In both cases, the Chinese have proven to be willing partners.

What can we make of China’s involvement? Do its actions represent a larger effort to spread coercive technology in order to bolster non-democratic leaders? What is driving these trends?

China’s proliferation of digital authoritarian tools presents serious challenges. Its technology is used by repressive regimes to quell mass protests, monitor political opponents, and keep autocratic leaders in power. However, China is not the only actor responsible for supplying repressive technology. Other countries, such as Israel, France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Russia, also supply advanced capabilities to repressive regimes — from location-tracking spyware and hi-resolution video surveillance, to hacking software, and censorship filtering applications. Analysts who overstate China’s role run the risk of oversimplifying a complex environment and ignoring other culpable actors who are supplying powerful capabilities to bad governments. If the United States truly wants to get serious about restricting the global spread of authoritarian technology, then it should push for comprehensive restrictions that would apply to both democratic suppliers as well as autocratic producers like China.

What is Digital Authoritarianism?

Being precise about how we define digital authoritarianism is crucial. A common definition entails “the use of digital information technology by authoritarian regimes to surveil, repress, and manipulate domestic and foreign populations.” This is a sensible starting point, but disaggregating digital authoritarianism by technology and tactic offers more insights.

Digital repression comprises six techniques: surveillance, censorship, social manipulation and harassment, cyber attacks, internet shutdowns, and targeted persecution against online users. These six techniques are not mutually exclusive. Intrusive spyware, for example, implanted by government security services on a user’s computer, is both a form of surveillance as well as a cyber attack. But each technique offers a specific set of objectives and draws from a unique set of tools in order to fulfill its function.

Digital tools are playing an increasingly prominent role in facilitating government control over citizens and blunting political challenges from opponents. States are deploying sophisticated surveillance tools augmented by artificial intelligence. Leaders are consolidating their rule by employing subversive disinformation strategies that foster disillusionment, cynicism and political disengagement. Many governments are employing sophisticated censorship strategies complemented by expansive “fake news” statutes that give authorities unbridled discretion to persecute political opponents and civil society activists. When all else fails, scores of states, particularly in Africa and South Asia, are willing to pull the plug on internet access and plunge their populations into digital isolation for extended periods.

Many experts pinpoint China as a key driver of digital repression. A new report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, for example, emphasizes that the “China model” of digital authoritarianism is becoming standard practice for non-democratic regimes. The 2018 Freedom on the Net report notes that Chinese companies are supplying facial recognition technology and advanced analytic tools to repressive regimes worldwide, and that China is promoting digital authoritarianism “as a way for governments to control their citizens through technology.” Some even anticipate that as like-minded countries “buy or emulate Chinese systems,” this will set the stage for an epic 21st century struggle between “liberal democracy and digital authoritarianism.”

China and Digital Authoritarianism

China is not a primary driver for the majority of these techniques. Rather, China only truly exerts outsized influence in the proliferation of surveillance technologies. For internet shutdowns and persecutions against online users, for example, China has no discernable global role. These actions are undertaken independently by state authorities. In fact, when it comes to internet shutdowns, Chinese authorities have adopted more sophisticated censorship tactics. The concept of completely shutting down the internet for extended periods of time is too blunt of an instrument to suit China’s purposes.

When it comes to social manipulation and disinformation online, China is relatively new to the game. As Oxford researchers Philip Howard and Samantha Bradshaw report, “until recently, we found that China rarely used social media to manipulate public opinion in other countries.” While Chinese activity in this area is increasing, the bulk of their efforts involve manipulating domestic speech or conducting foreign influence operations towards specific targets (e.g., Hong Kong protests, Taiwanese elections). There are scant examples of Chinese authorities equipping autocratic governments with hi-tech disinformation capabilities to enable campaigns against domestic opponents.

Similarly, when it comes to providing technology to facilitate state-sponsored cyber attacks — operations that manipulate software, data, computer systems, or networks to degrade operational capabilities or collect information — China is only one of many actors. This is not to suggest, of course, that Beijing does not hack. However, compared to liberal democracies, China is not a major exporter of hacking technology. Privacy International’s 2016 report on the private surveillance industry documented 528 companies peddling commercial intrusion technology (e.g., malicious code, mobile phone malware). Over 87 percent of these companies are based in OECD member states and 75 percent are headquartered in NATO countries.

When it comes to censorship, China offers an enticing model for fellow autocrats. China has taken steps to promote its approach through large-scale trainings of foreign officials, the provision of certain censorship technologies, and demands that international companies doing business in China accede to its content regulations no matter where they operate. However, local drivers are more determinative than China’s actions. Countries with high levels of censorship, like Thailand, have effectively weaponized libel and defamation laws to suppress dissent and tamp down free speech. While technology plays a prominent role in helping authorities suppress free speech, the foremost tools used to enforce content restrictions are legal in nature.

China’s Role in Spreading Surveillance Technology

When it comes to digital authoritarianism, China exerts most of its influence in the area of surveillance. Chinese companies, such as Huawei, are setting up advanced “safe city” platforms, offering facial recognition and intelligent video surveillance systems to repressive governments, and providing advanced analytic capabilities.

I recently undertook research on the global expansion of AI surveillance. AI-based surveillance offers many unique advantages over conventional tools. It enhances cost efficiencies, decreases reliance on security forces, and allows authorities to “cast a much wider net than traditional methods.” Throughout my research, I focused on three questions: Which countries are adopting AI surveillance technology? What specific types of AI surveillance are governments deploying? Which countries and companies are supplying this technology?

Governments in at least 75 of the 176 countries I surveyed deploy AI surveillance capabilities. They do so in three forms — safe city platforms, facial recognition systems, and smart policing. Chinese firms, led by Huawei, are the leading suppliers of AI surveillance tech used for public security worldwide. However, Chinese companies are not operating in isolation. Firms based in the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, and Israel are also key suppliers of public security surveillance.

The presence of AI surveillance technology does not mean that governments are using such technology for illegitimate purposes. The data simply indicates that these countries have a capability to undertake extensive surveillance if they so choose. Accordingly, liberal democracies with strong rule of law traditions and institutional checks and balances are far less likely to exploit this technology for repressive purposes.

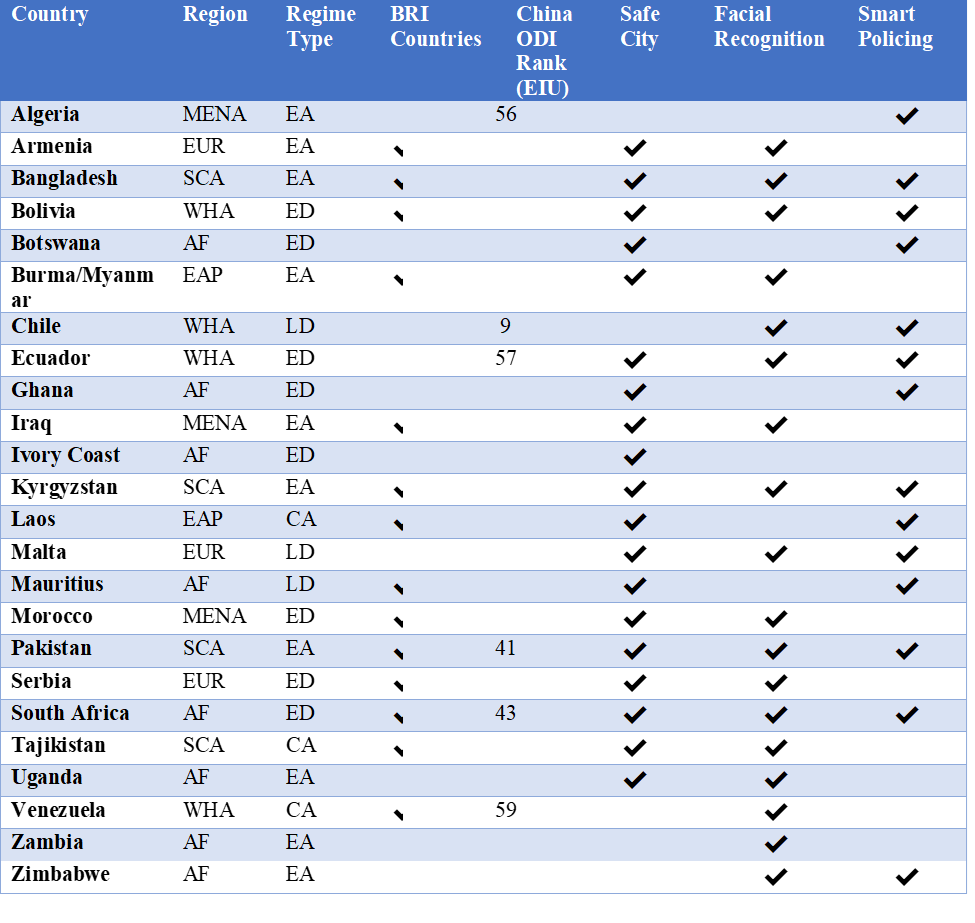

This raises an important follow-on question — in how many countries is China the main provider of AI surveillance for public security? Using data collected in the Carnegie report, I found that in 24 countries worldwide, Chinese firms appear to be the primary suppliers of AI surveillance technology to their respective governments. The appendix presents the full list of countries.

Of these 24 countries, many exhibit governance deficiencies — most are classified as hybrid regimes. They tend to share close geopolitical ties with China; 14 of 24 countries are members of the Belt and Road Initiative. Regionally, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are overrepresented with eight countries on the list. Finally, the group’s economic influence is small. South Africa leads the pack, ranking 33 out of 180 countries on 2017 global GDP. Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan cluster at the bottom — ranked 133, 147, and 151, respectively.

Implications

Many of the 24 countries would not be able to access advanced surveillance technology without China’s help. For these governments, China provides crucial equipment that enables security agencies to monitor citizens and disrupt political challenges as needed. In certain situations, Chinese companies are directly working on behalf of like-minded autocratic regimes. For example, Huawei employees have helped Ugandan and Zambian authorities spy on political opponents by intercepting communications, penetrating computers, and deploying location-tracking applications.

In exchange, China gains political influence, increases its economic leverage, and may even receive intelligence advantages (e.g., the African Union headquarters built by China were implanted with bugs that siphoned confidential data to Chinese authorities nightly from 2012 to 2017). Undoubtedly, membership in this group will increase in the coming years, representing an ominous sign about future trends of digital repression.

At the same time, countries considered to be client-states of Chinese repressive technology — such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, or Kazakhstan — source from multiple suppliers in a variety of countries. Saudi Arabia presents a useful example. Huawei is working with the government to build safe cities, Google and Microsoft operate cloud computing servers, U.K. arms maker BAE has provided mass surveillance systems, NEC sells facial recognition cameras, and Amazon and Alibaba may partner on a major smart city project in the kingdom. Most governments, especially those with resources, purposely refrain from relying on one supplier of technology.

No Evidence of a Grand Strategy

On balance, there are limited signs that China is pursuing a grand strategy to systematically proliferate digital authoritarian tools. Rather, China’s efforts vary by country, local context, and its own interests. As Cornell scholar Jessica Weiss observes, “The diffusion of digital authoritarianism is not the same thing as an intentional effort to remake other governments in China’s image. Although these systems can help governments monitor and control their people, how exactly they are used depends on local politics.” This remains a hotly debated issue in the policy and research communities. Experts such as Elizabeth Economy push back and assert that China is seeking to export a “variant of authoritarian capitalism.”

Why does this matter? Intent is critical to discerning geopolitical motives and future actions. If China is pursuing a comprehensive strategy to proliferate advanced technologies to non-democratic regimes in order to counter liberal alliances, this calls for developing specific policies in response. On the other hand, if China’s actions are less systematic than opportunistic (which they appear to be), then this significantly changes how democracies might react to China’s incursions.

U.S. policymakers should continue taking the threat posed by Chinese authoritarian technology seriously. Keeping pressure on the Chinese government to cease providing dangerous tools to the world’s most despotic regimes (and to compel China to stop deploying such technology at home, particularly in Xinjiang and Tibet) are important objectives. But they do not go far enough. The United States and other liberal democracies must also consider their own culpability in proliferating these tools. Coming up with a framework for responsible use that establishes penalties against companies that willfully and knowingly sell harmful products to repressive regimes would make a meaningful difference.

Conclusion

Digital repression is a broad term that encompasses a range of technologies and tactics. China has aggressively marketed technology in a specific area — advanced surveillance technology. But in other sectors, whether providing infiltration spyware or peddling sophisticated disinformation capabilities, it does not operate alone. Policymakers should keep a watchful eye on China’s actions. At the same time, they should be mindful that China is not the only country engaged in spreading the technologies and techniques of digital authoritarianism.

Appendix

Steven Feldstein is the Frank and Bethine Church Chair of Public Affairs at Boise State University, and a nonresident fellow at the Carnegie Endowment’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance program. From 2014 to 2017, he served as U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. He is writing a book on the global spread of digital repression.

Image: President of Russia