“If this country has been misled, if this committee, this Congress, has been misled by pretext into a war in which thousands of young men have died, and many more thousands have been crippled for life, and out of which their country has lost prestige, moral position in the world, the consequences are very great.’’

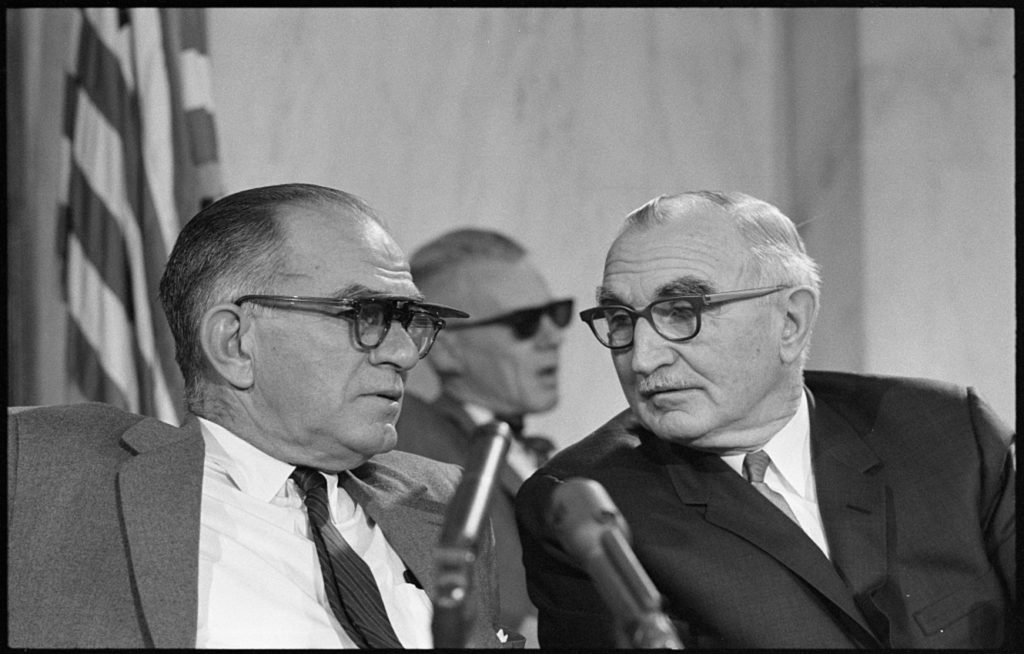

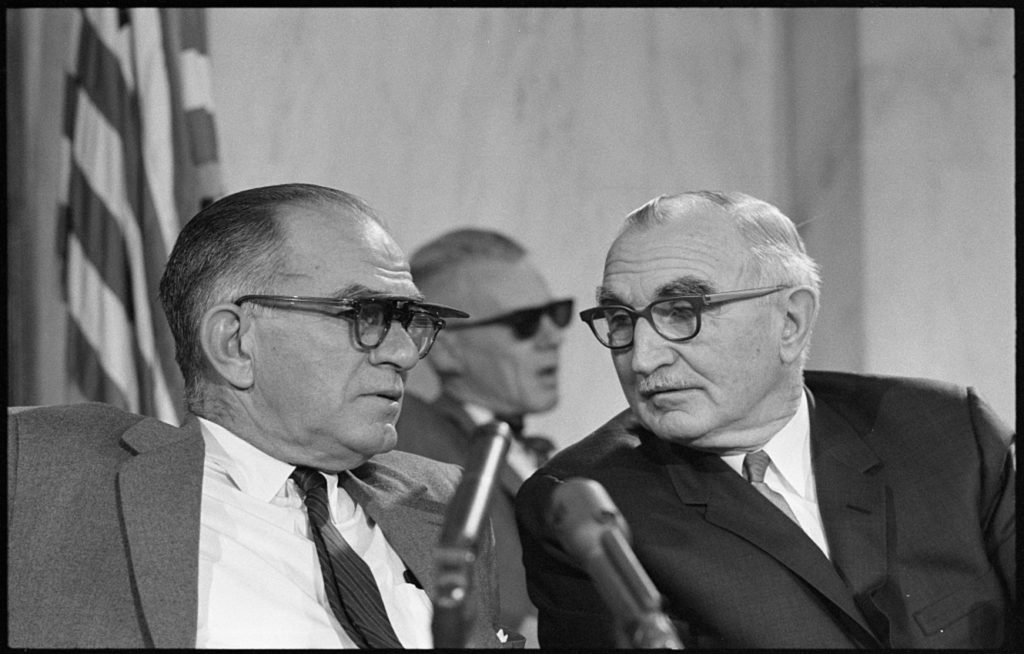

So said Sen. Albert Gore Sr. (D-TN) regarding the war in Vietnam in a Senate Foreign Relations Committee meeting on January 24, 1968.

He made his remarks in executive session. Very few Americans heard them. But two years earlier, Sen. J. William Fulbright of Arkansas, the chairman of the committee, initiated a series of public hearings on the war with the help of a few key allies, including Sens. Gore, Frank Church (D-ID), and Wayne Morse (D-OR). Over the next five years, members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee heard testimony from officials in the Johnson administration. But Fulbright also called skeptics of the war before his committee. As Joseph Fry explains in Debating Vietnam, witnesses opined on the fallacy of the domino theory, and the foolishness of dedicating resources in Southeast Asia that could have been more usefully spent elsewhere in the fight against global communism.

If there is a parallel to the present era, we may soon find out. Last week, for the first time in several years, witnesses testified publicly on the wisdom — or, in a few cases, the folly — of the war in Afghanistan. Such attention in Congress, including especially from the chairs of the relevant committees, may prove instrumental to ending America’s longest war. But that will depend upon whether Congress is interested in a diversity of opinion or is only willing to listen to those committed to an open-ended presence.

A Debate Most Intense

Fulbright proceeded with the hearings in spite of President Lyndon Johnson’s tireless efforts to stifle the very questions that they raised. Fulbright, the Arkansas Democrat who was once close with Johnson, faced the president’s wrath. Johnson actively worked to sabotage the hearings. He enlisted senators to spy on Fulbright and to block him where possible. He scheduled high-profile events to draw attention away from the hearings, and even directed the FBI to investigate Fulbright and his colleagues as communist sympathizers.

Fulbright knew that he couldn’t change Johnson’s mind on the war and was well aware of the political risks — but he went forward anyway. He sought, and often received, widespread media coverage, to maximize the hearings’ educational impact. They made public, and thus legitimated, dissent about a war that, prior to 1966, had received little notice. But Fulbright wasn’t merely challenging the administration’s position on the war for show. The committee members also sought to reassert their constitutional responsibilities with respect to war powers and to exert their influence over foreign policy, which had been steadily undermined and eroded over the previous two decades.

The range of experts who came to testify on the progress of the war included retired Army Gen. James Gavin, commander of the storied 82nd Airborne in World War II, and one of the first senior military officers to speak out publicly against the war. Gavin warned against escalating operations in Vietnam, arguing that a focus there would impede America’s ability to deal with other threats elsewhere.

Career diplomat George Kennan, the father of the U.S. policy of containment, and a widely respected foreign policy analyst, had also grown frustrated by Johnson’s Vietnam obsession. In his testimony, Kennan doubted the prospects of military success and questioned the strategic importance of Vietnam within the wider anti-communist crusade. “If we were not already involved as we are today in Vietnam,” Kennan testified, “I would know of no reason why we would wish to become involved, and I can think of several reasons why we would wish not to.”

And Kennan even confessed that his famous “X” article, which spelled out the rationale for containment, was flawed. Because he had not specified that communism could not be stopped everywhere, Kennan came to realize how his arguments could be used to justify open-ended conflicts anywhere. He advised that the United States withdraw “as soon as this could be done without inordinate damage to our prestige or stability in the area” to avoid risking war with China.

Gavin and Kennan’s appearances in 1966 advanced Fulbright’s goal of galvanizing a wider public debate. In the ensuing years, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee heard from a wide variety of witnesses, including David Bell, former administrator of the Agency for International Development, and leading scholars such as Hans Morgenthau, A. Doak Barnett, and John King Fairbank. One of the last witnesses to testify before one of Fulbright’s hearings was a young John Kerry, speaking as a Vietnam veteran against the war. Kerry’s testimony drew attention to war’s horrible effects on the Vietnamese people and on returning veterans.

Though Johnson would not allow Defense Secretary Robert McNamara to testify, he permitted Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and Gen. (ret.) Maxwell Taylor — the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, then U.S. ambassador to Saigon — to appear before the committee in February 1966. Both were subjected to intense questioning, including scrutiny of previous testimony that the committee had received in private, executive sessions.

As Fry explains, Rusk’s testimony reflected his unwillingness “to come to grips with his and the administration’s miscalculation and flawed understanding of the struggle.” Similarly, Taylor merely reiterated the administration’s view that only the failure of the will of the American people would lead to defeat in Vietnam. “I know of no new strategic proposal which would serve as a better alternative to the one which I have described.” Both men emphasized that preventing the spread of communism to South Vietnam was crucial to America’s containment strategy — directly contradicting the author of that strategy’s claims. If Saigon were to fall, Rusk and Taylor averred, it would clear the way for China and the Soviet Union to project their influence, not just regionally, but globally. Failure in Vietnam, they concluded, would destroy American credibility, and render the United States virtually powerless.

We will never know the true impact of Fulbright’s hearings on public opinion. Whether they were a cause or a consequence of rising public disquiet about the war is impossible to gauge. But Johnson’s determination to stop them speaks to his own anxiety about greater public scrutiny. He would have much preferred for Americans to spend lives and money without asking what for.

A Conspiracy of Silence

If Fulbright deserves credit for thwarting the president’s plans and for raising public awareness about the war in Vietnam, his successors deserve blame for failing to do so with respect to the war in Afghanistan, now in its 19th year. Before this week, few members of Congress — and, in particular, the chairs of the relevant committees — seemed particularly interested in the subject.

For example, the present chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, James Risch (R-ID), has been in that job for 13 months. According to his committee’s own website, there have been 33 public hearings (not counting those dealing with routine business or nominations before either the full committee or its subcommittees), during his tenure. None have focused on the war in Afghanistan.

The previous chairman, Bob Corker (R-TN), didn’t do any better. In 2017 and 2018 (during the 115th Congress’s term), the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and its subcommittees convened 83 topical public hearings (i.e. not for routine business or nominations). Exactly one hearing addressed the war in Afghanistan — and it featured testimony from two officials responsible for implementing the Trump administration’s policy there. Anyone daring to question why the United States had failed to achieve its objectives, including outside experts, apparently wasn’t welcome.

It would be reasonable to believe that U.S. government officials testifying under oath before Congress would not offer up information that challenged U.S. government policy, or, for that matter, that their remarks would not differ substantially from what one might hear in a press conference at the State Department or the Pentagon.

But that reasonable assumption was shattered with the publication late last year of the Washington Post series “The Afghanistan Papers: A Secret History of the War.” Based on materials obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request from the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, the Post exposed harsh criticism of the war, and of U.S. strategy in the region. Most shocking was the revelation that the confidence in the success of the war and reconstruction in Afghanistan that many U.S. government officials displayed varied drastically from the honest — and far more pessimistic — assessments of individuals on the ground.

The Usual Suspects

Within days of the release of the “The Afghanistan Papers,” Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, penned a letter to the chairman, Sen. Jim Inhofe (R-OK). She requested a public hearing “to examine the questions raised by this reporting and provide clarity with respect to our strategy in Afghanistan, a clear definition of success, and an honest and complete review of the obstacles on the ground.” Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), another Senate Armed Services Committee member, agreed via tweet that the committee should hear from Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and others in the Trump administration responsible for U.S. policy.

Inhofe finally complied with their request on February 11th, presiding before an empty committee room that heard only from individuals committed to sustaining the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan. Witnesses included Gen. (ret.) John Keane, former vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army; Colin Jackson, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia; and Brig. Gen. (ret.) Kimberly Field, who all touted ongoing successes within the Afghan security forces. They pointed to the Afghan government’s progress in improving the lives of women and children. And all three witnesses cast doubt on the prospects for a negotiated end to the war. In his written testimony, Jackson’s warned “A peace that deserts our allies and enables our enemies to seize power will raise the risks of renewed terrorist attacks on the American homeland by Al Qaeda and [the Islamic State in Afghanistan].”

Sen. Angus King (I-ME) fixed on the “haven for terrorist” justification for remaining in Afghanistan. He noted “there are other places that can be havens,” and he worried that the United States risked playing “geopolitical whack-a-mole.” Is this a case, he asked, where “we’re going to focus in one place and our adversaries are going to rise up somewhere else?” Jackson appreciated the problem but said that Afghanistan would become a haven “if U.S. forces were not physically located there.” Keane concurred. “A physical presence is essential,” he said.

King followed up. “We’ve maintained a troop presence in Japan, South Korea, Germany, other parts of Europe, for 70 years,” he observed. Is Afghanistan like that, “a place where we need an indefinite presence…?”

Keane emphatically embraced that parallel. He conceded that it was “a political apple that leaders are not willing to swallow and talk to the American people honestly about.” But, nevertheless, “we could possibly have to have a counterterrorism force … [in] Afghanistan, as long as that threat is there, indefinitely.”

King noted that the witnesses’ testimony, and the focus on denying a physical safe haven, reminded him of the Vietnam-era domino theory, which had used fear of communism as a justification for endless war. Today, the threat is terrorism, but the solution is the same: remain in Afghanistan until the threat disappears — which may be never. And Inhofe’s hearing served mostly as a vehicle for former high-level U.S. officials to reaffirm the wisdom of U.S. strategy. In other words, the kind of thing that can be heard almost any day, in countless other venues. No wonder the committee room was empty.

A Different Hearing, with a Different Set of Witnesses

Later the same day, Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) convened a hearing before the Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management Subcommittee, under the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs: “The Afghanistan Papers: Costs and Benefits of America’s Longest War.” Paul’s opening remarks emphasized the “extraordinarily troubling” nature of the “Afghanistan Papers” for confirming the suspicions of many Americans and lawmakers, namely that Afghanistan is a “U.S. war effort severely impaired by mission creep and suffering from a complete absence of clear and achievable objectives.” For these reasons, the subcommittee heard from witnesses who were involved in the SIGAR “Lessons Learned” project, and who were willing to honestly discuss the Post’s report.

The first witness was John Sopko, the special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction. That isn’t exactly newsworthy. Sopko, a relentless critic of the war’s reconstruction efforts, has testified before Congress on numerous occasions, including at least two other times since the start of the year. However, as he noted in his opening remarks, Paul’s subcommittee was the first to focus, in particular, on his office’s “Lessons Learned Program.”

Other witnesses included retired Army General Douglas E. Lute, the White House’s “war czar for Afghanistan” as the Post described him, and career diplomat Richard A. Boucher, who served as assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asian affairs from 2006 to 2009, as well as retired Lt. Col. Daniel L. Davis, a veteran of the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and now a senior fellow at Defense Priorities.

The “Afghanistan Papers” revealed the confusion surrounding the mission in Afghanistan. In a “Lessons Learned” interview, Boucher noted how the enemy and the mission continually shifted and expanded. “If there was ever a notion of mission creep it is Afghanistan,” he said. Lute admitted that they “were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan — we didn’t know what we were doing,” and yet U.S. officials continued with vast reconstruction and nation-building plans. But Lute also criticized Congress for its willingness to appropriate whatever the administration asked for, without ever asking questions about the underlying strategy.

Lute and Boucher had once supported the war, but their views had evolved over time. In his testimony, Lute urged U.S. policymakers to “prioritize politics and diplomacy to move toward compromises that end the war in Afghanistan.” He recommended that “U.S. economic support to Afghanistan … be conditioned on progress by the Afghan Government,” and called for “alternatives to the current counter-terrorism methods, including enhancing the most capable Afghan forces, intelligence gathering that does not rely on a costly U.S. troop presence, and off-shore basing for U.S. forces, for example in bases in the Persian Gulf.”

Boucher echoed many of these arguments, downplaying the use of force, and emphasizing the importance of diplomacy. The effort “to eliminate the terrorists and all those who harbor them will never be achieved by military means,” he noted. Rather, “It will be achieved by capable governments around the globe who are able to provide benefits to their populations. That requires more diplomacy, not more interventions.” “It is time,” he concluded, “to convert our presence to diplomatic support, aid channeled through the Afghan government and a minimal military footprint. It’s time to come home.”

Davis, unlike Lute and Boucher, appeared before the committee as a long-time critic of the war. In 2012, he had detailed how reports to Congress had deceived the American people about the progress and realities of the war, and went public with his findings. He had put his career and reputation on the line in order to reveal what soldiers and others serving on the ground were really seeing in Afghanistan. But the Pentagon had dismissed his findings, as he explained in his testimony, as “one person’s viewpoint.”

Now, eight years later, he was repeating the same warnings. In particular, and counter to the arguments made that morning before Inhofe’s Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, Davis dismissed the notion that withdrawing troops from Afghanistan would bring another 9/11 as a “pernicious myth.” Such claims, he testified, underestimated the strength of U.S. counterterrorism capabilities in the region and the Afghan people’s willingness to shoulder the burdens that may fall upon them should the United States pull out.

Oversight Indeed

It is rarely politically advantageous to take a stand on a controversial foreign policy issue, and especially for co-partisans. Indeed, Fulbright suffered President Johnson’s wrath for daring to peel back the curtain on a war that LBJ desperately wanted to be kept hidden from public view. Today, Republicans have little appetite for daring to question the Trump White House, but many Democrats were quiescent under President Barack Obama.

And yet we should celebrate the rare occasions when members of Congress are willing to do their jobs despite the political risks. Any House or Senate committee chair can have a big impact on public understanding, and nowhere is that more apparent than in questions of war and peace. With due credit to Sen. Paul, we should also expect to see additional hearings on the war in Afghanistan before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and in the House as well.

Equally critical, the hearings should include testimony from those outside of the administration, and who did not have a hand in crafting the policies under review, and thus are understandably motivated to portray the war in the most favorable light. Those who are willing to question the underlying rationales, and to offer genuine alternatives to a permanent troop presence, deserve to be heard. If their arguments are insufficiently compelling, then the advocates for continuing the war indefinitely should have nothing to worry about.

Few public policies are so sacrosanct that they can’t weather close scrutiny, and members of Congress should lead such an effort. To do otherwise isn’t merely a failure of oversight. It’s a dereliction of duty.

Christopher Preble is vice president for defense and foreign policy studies at the Cato Institute, where Lauren Sander is a research associate.

Image: Library of Congress