Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Gresham’s Law states that bad money drives out good money, but anyone who has spent time around Washington, D.C., knows that this law can safely be applied to information too — bad information tends to drive out good information. Such is the case with America’s assessments of other countries’ military and economic power. Defense spending is one of the most commonly used measures for gauging a country’s potential military power, setting expectations of what the military balance might look like in the future. It helps give us a sense of how much of a state’s economic power is being converted into military power. Well, in theory it should, if we knew how to measure it right, but comparing defense spending across countries is a complicated task. As a consequence, the United States doesn’t really know where its military expenditure stands in relation to that of its principal adversaries, what kind of military capability they’re getting for their money, and whether the balance of power is likely to improve or worsen over time.

Policymakers are barraged by a daily stream of think tank reports, academic writing, and media stories competing for their perceptions. For example, by cherry-picking a few gross measures, including military expenditure, a recent RAND report caricatured Russia as a weakling rogue state. Major newspapers generate erroneous headlines: many ran stories asserting that in 2017 Russian defense spending declined by a fifth . In our experience, both in Washington and London, decision-makers have little time to investigate or read and tend to believe many of the headlines they come across. Indeed, rarely does a discussion take place on Russia or China without a series of assumptions being voiced based on questionable assessments of relative power when it comes to GDP, defense spending, or demographics.

Of course, a necessary precursor to finding measures that matter is knowing how to measure in the first place. This is a challenge we hope to briefly take up here. It is hardly an academic question. Strategic implications abound for America’s pursuit of a favorable regional military balance in Europe and decisive military advantages over its adversaries. In our view, despite its tremendous size, U.S. defense spending does not actually dwarf that of the rest of the world. This also raises some uncomfortable questions about the ability of the United States to attain deterrence by denial against competing revisionist powers. The disparity is especially evident when looking at the case of Russian military expenditure, which is much larger than it appears, though a fair assessment of Chinese defense spending would also yield pessimistic expectations about the future balance of military power.

Why Russia Gets More Bang for the Ruble

Based on the annual average dollar-to-ruble exchange rates, Russia is typically depicted as spending in the region of $60 billion per year on its military. This is roughly in line with the defense spending of medium-sized powers like the United Kingdom and France. However, anybody familiar with Russia’s military modernization program over the past decade will see the illogic: how can a military budget the size of the United Kingdom’s be used to maintain over a million personnel while simultaneously procuring vast quantities of capable military equipment?

Russian procurement dwarfs that of most European powers combined. Beyond delivering large quantities of weaponry for today’s forces, Russia’s scientists and research institutes are far along in development of hypersonic weapons, such as Tsirkon and Avangard, along with next-generation air defense systems like S-500. This volume of procurement and research and development should not be possible with a military budget ostensibly the same size as the United Kingdom’s. When theory checks in with practice, the problem with the approaches that return such answers is plain for anyone to see.

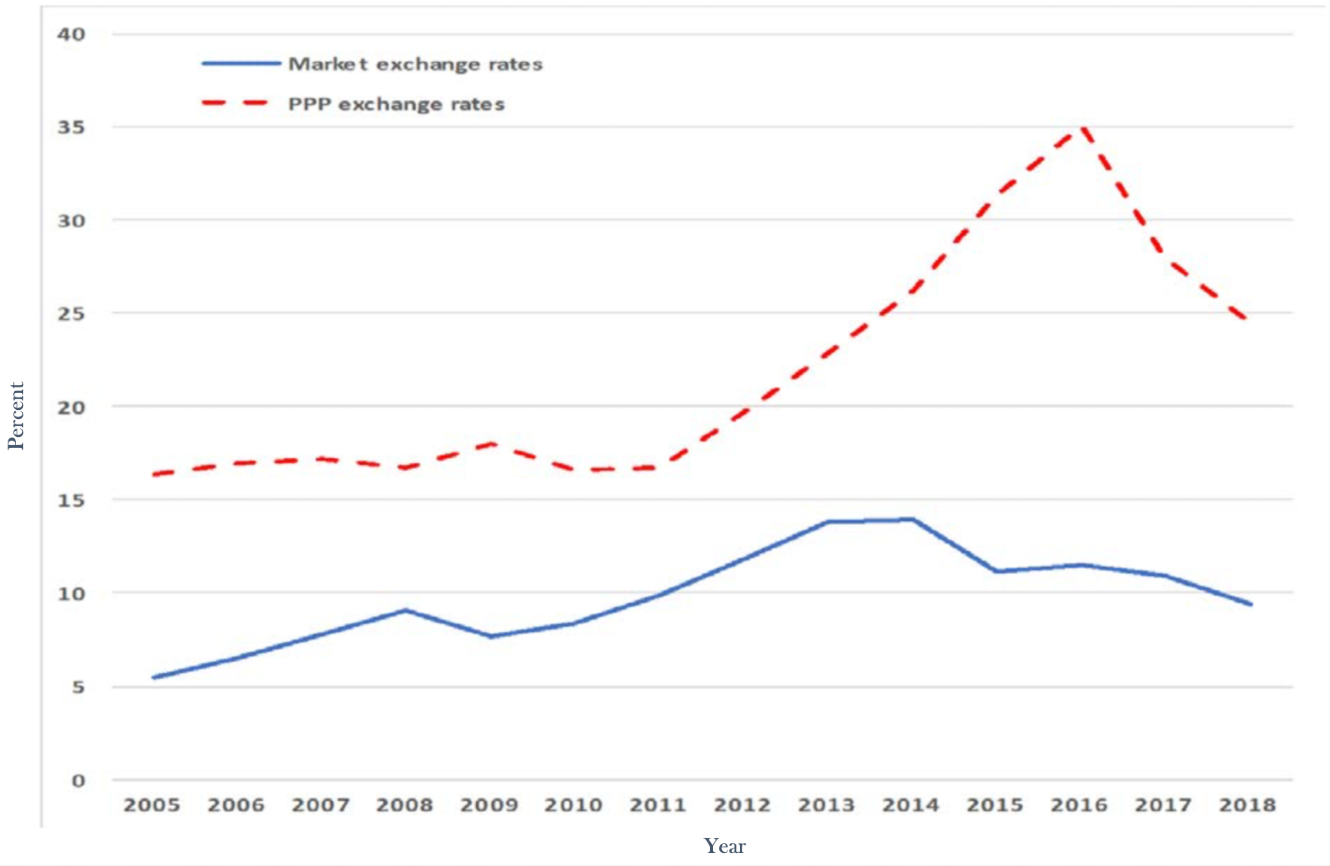

The reason for this apparent contradiction is that the use of market exchange rates grossly understates the real volume of Russian military expenditure (and that of other countries with smaller per-capita incomes, like China). Instead, any analysis of comparative military expenditure should be based on the use of purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates rather than market exchange rates. This alternative method takes differences in costs between countries into account. As we demonstrate, despite some shortcomings, PPP is a much more methodologically robust and defensible method of comparing defense spending across countries than the method of comparing spending using the market exchange rates that are commonly used by think tanks and academics. Using PPP, one finds that Russia’s effective military expenditure actually ranged between $150 billion and $180 billion annually over the last five years. That figure is conservative; taking into account hidden or obfuscated military expenditure, Russia may well come in at around $200 billion.

To put it simply, calculating Russian military expenditure based on purchasing power means that the United States spends only about four times more than Russia on defense, rather than ten times more when using market exchange rates. But this remains a crude comparison. The gap is even narrower when one digs into the differences in how this money is spent. At nearly 50 percent of federal budget spending on national defense, a large proportion of the Russian defense budget goes to procurement and research and development. By comparison, in other countries with large defense budgets, procurement spending tends to be much lower: in India, the United States, and the United Kingdom, spending is at about 20–25 percent.

Unlike some other large military spenders — for example, Saudi Arabia and India — Russia also produces most of its weaponry itself and does not buy its equipment from countries with higher costs. This means that effective Russian military expenditure is much larger given that a ruble spent at home buys considerably more than a dollar spent abroad. And, despite Russia’s largely stagnant economy, this higher level of spending has proven far more durable than media narratives have suggested.

Perhaps most importantly, the more methodologically sound approach to comparing defense spending based on PPP illustrates that the gap between U.S. expenditure on the one hand and that of Russia and China on the other has closed dramatically over the past 15 years. Today, when taken together, spending by Russia and China is roughly equal to U.S. defense expenditure, with Russia representing a much larger share than previously recognized.

Figure 1: Russian military expenditure as a share of U.S expenditure (percent), 2005–2018 (Richard Connolly)

Getting Defense Comparisons Right

Much of this confusion over the relative scale of Russian military expenditure is explained by differences in how analysts choose to measure military expenditure. When U.S. dollars calculated at market exchange rates are used to measure military expenditure across countries, the data can fluctuate wildly over time, more often than not due to changes in relative exchange rates rather than because of any changes in a given country’s military expenditure. This was vividly illustrated in 2014–2015 when the ruble depreciated sharply vis-à-vis the dollar, largely due to collapse in the global price of oil. Russian military expenditure, calculated at market exchange rates, was presented as having declined, even if in ruble terms, military expenditure was in fact growing briskly.

But exchange rate volatility is hardly the main reason why market exchange rates should not be used to measure military expenditure in Russia, China, or any other country. This is because converting military expenditure measured in national currencies to a common currency — usually the U.S. dollar — at market exchange rates conceals important differences in purchasing power across countries. Many goods and services have different relative prices within a country, with non-traded goods and services being relatively less expensive in poorer countries. This can result in military expenditure being drastically understated in countries with lower income levels, and correspondingly lower costs, than the United States.

Comparing defense expenditures using market exchange rate methodologies results in a parade of erroneous figures, which can be observed in annual think tank assessments, such as those made by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) or the International Institute for Strategic Studies flagship publication The Military Balance. The problem was best illustrated earlier this spring when SIPRI announced that Russian defense spending in 2018 had fallen behind Saudi Arabia and France to sixth in the world at $61.4 billion. Similarly, a chapter in The Military Balance comparing defense expenditure shows Russian expenditure to be a paltry $45 billion based on constant 2010 market exchange rates, less than that of the United Kingdom. These of course are remarkable assertions. One need not be a Russian military analyst to have a general appreciation for the fact that the Russian armed forces, including conventional and nuclear components, are vastly larger in size, greater in fielded capability, and in a higher state of readiness than those of France or the United Kingdom.

The most appropriate method for taking differences in relative costs across countries into account is, therefore, to use a PPP exchange rate. Today the International Monetary Fund calculates an implied PPP exchange rate of 23.4 rubles to the dollar. Given that the actual market exchange rate is 65 rubles to the dollar, this would suggest that the value of economic activity in Russia is over two and a half times larger than implied by the prevailing market exchange rate.

An equally important problem is how one compares GDP and relative living standards. Russia’s economy, which may seem to be closer to the size of South Korea’s based on simplistic conversions at current market exchange rates, is more accurately reflected as the sixth largest economy in the world. This is because while market exchange rates are appropriate for measuring the value of internationally traded goods, PPP rates should be used when measuring non-traded goods and services. It is precisely these non-traded goods and services that tend to dominate military expenditure in countries like Russia that have sizeable and largely autarkic defense industries.

A Closer Look at Russian Defense Spending

In a recently published research paper sponsored by CNA, Russian military expenditure is calculated using PPP exchange rates that account for differences in the cost of inputs in Russian rubles. The use of purchasing power–based estimates reveals not only that the level of Russian military expenditure is considerably higher than market exchange rate–based estimates suggest, but that this level has been much higher than commonly estimated since the 1990s.

Second, PPP-based estimates show that the rate of growth of Russian military expenditure was slower than suggested by market exchange rate–based estimates.

Third, Russia’s rate of growth in military expenditure since 2005 was also lower than that of other powers, such as China and India. This is partially due to the fact that Russia started from a higher base, but it also reflects the fact that China, India, Saudi Arabia, and many other non-Western powers have been engaged in a robust expansion of military spending.

Fourth, after adjusting PPP-based estimates of total military expenditure for imported military equipment, Russia has held a steady position as the world’s fourth largest military spender, behind the United States, China, and India.

As a middle-income country with lower costs, Russia spends much less maintaining its military than Western states, with about a third of its force made up of conscripts. Even if a conscript force performs worse, on average, than an all-volunteer force, conscripts can readily achieve a state’s military objectives because military operations are performed by specific, operationally assigned forces in defined geographic areas, not by notional forces logged in Excel spreadsheets of nationwide capability. Russia’s 2014 Crimea operation and 2015 intervention in Syria illustrate this point. As a result, the Russian General Staff gets a lot more capability out of its military expenditure than many other higher-cost militaries. While some countries like India may effectively spend more on paper based on PPP, the reality is that the Russian defense budget over time allows Moscow to wield a much bigger and pointier stick.

Russia’s state armament program has been hampered by two factors: a messy divorce with Ukraine’s defense sector and the loss of access to certain enabling technologies imported from the West. This led to major delays in several sectors and costly efforts at import substitutions, chiefly of components from Ukraine. However, this has over time made the Russian military industrial complex much more self-sufficient and even less dependent on imports than it was before sanctions were imposed, making PPP even more useful for measuring the true level of Russian defense spending. Furthermore, the Russian state has made sure that the defense sector is on a diet in terms of the profits it is allowed to make from state defense orders. While this led to a debt bubble within the Russian defense industry, it also suggests that the state is able to get more output from the defense sector relative to other sectors of the economy.

Although the level of Russian defense spending is higher than many previously thought, it is also true that it is declining as a share of GDP. The Russian government has chosen to let defense expenditure plateau for two reasons: first, because a large amount of equipment was successfully procured between 2011 and 2016, resulting in significant modernization of a previously aging force; and second, to avoid the sort of runaway defense spending that contributed to the Soviet Union’s economic ruin. But this slowdown in the growth of defense spending should not be confused with slashing defense spending to levels that might drastically reduce Russia’s military capability. There is no evidence that such steep reductions are taking place. Instead, Russia is charting a middle course, not killing itself with unsustainable Soviet-style spending on defense, but equally avoiding painful reductions in order to meet the reformists’ demands.

Better Data for Better Strategy

During the Cold War, estimating Soviet defense spending proved one of the most hotly contested subjects within the U.S. defense community because it was an essential input into U.S. strategy toward a superpower adversary. Differing estimates of Soviet expenditure were produced by the CIA, which based its estimates on a wealth of unclassified and classified material, and the analysts located outside the intelligence community who relied on open-source material. As the Soviet economy stagnated in the 1970s and 1980s, debates over the ability of the Soviet economy to support the burden of the country’s vast military expenditure intensified.

This conversation is no less important today. The strategy community needs better measures and a smarter conversation on military expenditure. Overestimating or underestimating adversaries can lead to the misallocation of scarce resources or bad strategy. President John F. Kennedy and President Ronald Reagan both entered office mistakenly believing the United States was falling behind its Soviet adversary — the opposite was true. Perhaps more dangerously, relying on simple but often distorted measures of relative capabilities raises the prospect of U.S. policymakers, like their British counterparts a century before them, failing to appreciate the erosion in their own country’s military power.

It is certainly possible to be better at assessing Russia’s military expenditure than it was 30 years ago. Although it is true that the Russian defense budget has become increasingly opaque in recent years, America has much better information today on the state of the Russian economy and its defense spending than it did when trying to assess the Soviet Union’s capabilities.

Unfortunately, greater information has not translated into better analysis or more informed discourse among policymakers and academics alike on the real balance of power between the United States and its supposed competitors. Measuring military power is fraught with difficulty because it can be so context-driven and scenario-based. But if Russian defense spending is much larger than meets the eye, it suggests that the United States will struggle to maintain a favorable balance of power over time given increased pressure from China. The U.S. defense budget is not as vastly superior as it seems, and given the numerous contingencies Washington faces, U.S. military expenditure by itself will not naturally confer the ability to deter Russia in Europe. Simultaneous pursuit of deterrence by denial against both countries near their borders, seeking to prevent so-called faits accomplis via direct defense, is likely to prove an unaffordable and unrealistic strategy for the United States.

Meanwhile, those interested in the structural distribution of power, particularly realists, need to look again at their arguments, which bend towards the conventional wisdom that Russia is a tiny economy in decline. A fixation on China in strategist circles overlooks the simple fact that while Russia is certainly not going to be the world’s next superpower, it remains one of the largest economies and has a defense budget sufficient to maintain a military capable of challenging the United States conventionally. Beyond military expenditure, many of the other parameters used to set expectations of a country’s rise or decline, such as demographics, require greater scrutiny as they are probably based on equally questionable data. The truth is that at times defense economists are decidedly lazy in how they measure power, compare key national indicators, and form their expectations about the future balance. There is also a tendency to assume that rise and decline are secular trends, i.e., that China will continue rising as Russia declines. The historical track record of these two powers suggests otherwise.

Russian military expenditure, and as a consequence the potential for Russia to sustain its military power, is much more durable and less prone to fluctuations than it might appear. The implication is that even at its current anemic rate of economic growth, Russia is likely to be able to sustain a considerable level of military expenditure, posing an enduring challenge to the United States for the foreseeable decades. While ours is an exploratory analysis, it suggests that Russian defense spending is not prone to wild swings, nor has it been dramatically affected by changes in oil prices or U.S. sanctions. Given the disparity in national budget allocations, even as European allies increase their defense spending, Moscow is not going to struggle in keeping pace.

Michael Kofman is director and senior research scientist at CNA Corporation and a fellow at the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute. Previously he served as program manager at the National Defense University. The views expressed here are his own.

Richard Connolly is director of the Centre for Russian, European, and Eurasian Studies at the University of Birmingham and senior lecturer in political economy. His research and teaching are principally concerned with the political economy of Russia and Eurasia.

Image: Kremlin