Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

At 10:05:24 Zulu (1:05 p.m. local), on the morning of Dec. 28, 1998, Lt. Col. Al “Bat” Cross and I were in Coors 01, an F-15E Strike Eagle, southbound northeast of Mosul, Iraq, over the northern no-fly zone. The 494th Fighter Squadron, the “Black Panthers”, were deployed to Turkey from the home of the 48th (“Liberty”) Wing, Royal Air Force Lakenheath, in the east of England. As part of Operation Northern Watch, we were enforcing the zone, prepared to engage and destroy Iraqi aircraft operating north of the 36th parallel. After almost eight years, this was a routine and normally uneventful combat mission. A second later, that routine was shattered by our radar warning gear, announcing in strident tones that a missile guidance signal was radiating nearby. In the span of a heartbeat, Bat had the aircraft in a descending, 4G left-hand turn with the throttles parked as far forward as they would go, as I made the radio call announcing our callsign, condition, and location.

“Coors one, mud three, defensive, bullseye three four seven, twenty six, heading east.”

The crew of Bud 02, northwest of Mosul, received the same tickle from their radar warning gear, missile guidance beams being notoriously non-directional. Fax, piloting Bud 02, made his radio call at the same time as I made mine — which one was heard over the radio depended on which aircraft was closer to you. Thirty seconds later, it became clear who the target was, as an Iraqi SA-3 missile site ripped off two “Goa” surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) in the direction of Coors 01. Just before lunch, three days after Christmas, Iraqi air defense SAM operators in their 4th Air Defense sector fired what were arguably the first shots of the Second Gulf War.

Surprise!

It was almost just another day in the no-fly zone, but not quite. Operation Desert Fox, from December 16 to 19, had been ordered to punish the Iraqis for their noncompliance with the weapons inspection regimen imposed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 687. Perversely, while cruise missiles pummeled targets in Iraq, those of us already charged with enforcing the northern no-fly zone were told to stand down. That meant that the Iraqis had been granted nearly two weeks to shuffle their northern air defenses without any observation by the photoreconnaissance aircraft attached to Combined Task Force Northern Watch. December 28th was our first day back in the zone after being grounded. We knew only where the air defenses used to be.

The British and American Combined Task Force Northern Watch operated out of Incirlik Airbase in Turkey. An F-15 pilot and one of the key architects of the air campaign plan in Desert Storm, then-Brig. Gen. Dave “Zatar” Deptula was the commander, with a Turkish general officer as his deputy. At our disposal, we had detachments of fighters; F-16, F-15E, and F-15C providing our conventional firepower, along with Navy and Marine Corps EA-6B Prowlers to suppress enemy air defenses and a pair of Royal Air Force Tornado GR4As giving our photoreconnaissance capability. As always, we were supported by an E-3C Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), the ubiquitous and utterly necessary KC-135 refueling tankers, and a detachment of combat rescue aircraft on alert in case things went sideways.

Over the years, the task force had fallen into a passive posture. Despite the occasional downing of an Iraqi aircraft, ground-based defenses were left alone. The last time an Iraqi radar had been destroyed in the northern no-fly zone had occurred in 1994, when a dedicated radar hunter, an F-4G Wild Weasel, rammed an antiradiation missile through a fire control radar. Even with occasional provocations by Iraqi air defenses, coalition aircraft generally withdrew in the face of hostile ground fire. A culture of risk aversion had crept in, which the Iraqis had years to observe. They fired and we left. The last such event had been the 1996 surface-to-air missile “SAMbush” of a flight of F-16s in 1996, which went unpunished. Unbeknownst to the Iraqis, Deptula, the new task force commander, did not share his predecessor’s risk aversion and had changed the rules of engagement. If fired upon, we were authorized to respond immediately with lethal force.

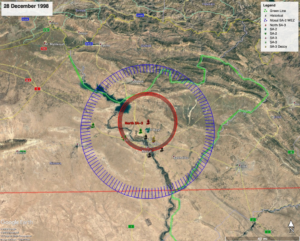

Figure 1: The northern no-fly zone on 28 December 1998. The red line marks the southern boundary of the no-fly zone, while the “green line” marked the de facto border between Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and the Kurdish autonomous zone. The red circle denotes the offending SA-3 engagement zone, watched over by the longer-range SA-2 in blue.

Engagement

The weather was barely good enough to fly, with cloud layers underneath us that obscured the ground in and north of Mosul. Indeed, the photo runs were cancelled because of the clouds, which cleared too slowly for the Tornado’s scheduled times. That left the rest of the force, especially the F-16s, dipping our toes in the water, while the Strike Eagles used their powerful radars to examine known missile sites to see if anyone was home. In the meantime, we established our normal combat air patrols, radars looking south for Iraqi air activity. Northeast of Mosul, three Iraqi officers in a Russian-built control van for the SA-3 missile system watched their scopes for a pair of Strike Eagles penetrating their zone. As Coors 01 entered range, they brought up the missile guidance beam, necessary to guide missiles against targets acquired either with the radar, or more surreptitiously through a passive (and therefore radar-silent) television system.

They certainly got our attention. In the early seconds, we only had a warning of a radar threat, without precise location data that would tell us where they were. Mosul was to our right. Assuming that the SAM battery was close to Mosul (because that’s where they always were), Bat “dragged out,” which is airman parlance for running away bravely. He guessed right — by the time the missiles blasted off their launch rails, we were nose down with the afterburners in full grunt, punching through the sound barrier in the opposite direction from the missile battery. I never saw the missiles launch, and the collection of non-standard, overly excited radio calls from unmolested aircraft were no help. “Launch, SAM launch!” “Where?” “Your two o’clock.” From my vantage point, turned around looking between our twin tails, the launch location was obscured by the fuselage. By the time I saw the missiles in flight, they probably didn’t have the energy to catch us, and the pair detonated above us and well behind. Game on.

Torch and Ice, flying off our wing in Coors 02, were unthreatened. Ice moved his LANTIRN (low altitude navigation and targeting infrared for night) targeting pod, which contains a telescopic thermal camera array, to focus on the cloud of dust that accompanied the missile launch. Light surface winds left the cloud floating in nearly still air, for all the world a giant, dark arrow pointing towards the offending missile battery (figure 3). While Bat and I outran supersonic doom, our wingman located the missile battery and broadcast it over the radio. To further highlight themselves, the Iraqi operators launched a third missile four minutes later, pointed at where we had been. By then I had our targeting pod aimed at the missile site and saw the launch. SA-3s are fast.

Figure 2: The picture from the LANTIRN after the third missile launch. The image in the jet is not much better than the screen capture. In LANTIRN, hot objects show in shades of white, while cool ones are darker. In the top left is Mosul, with the village of Batnay at center right. The dark cloud near the crosshairs is the cloud from the third missile launch. Clouds in the foreground are, in fact, clouds.

“Cougar, Devil one. I’d like to start coordination for a DEAD, against the Mosul SA-3” (pronounced “deed” and meaning destruction of enemy air defenses). At 10:11z, Devil 01, the F-16 pilot who commanded the defense suppression element, called Cougar, our AWACS, for clearance to respond. Technically, we were authorized immediate response under the new rules, but old habits die hard — and Cougar was already ahead of the game, making the request on satellite communications. Coors 02 had already designated the site, telling his computer where the target was. As it turned out, it was “site 44,” a previous emplacement that was already programmed into our navigation systems, simply awaiting a call-up. At 10:12z, Cougar called back: “Devil one, DEAD is approved, roll call.” Seventeen seconds later, all aircraft had responded.

Execution

While this was not a preplanned strike, we were not totally winging it. Having the location numbered and programmed was a help. The 494th Fighter Squadron was also the right squadron for the job. The Panthers had also practiced an attack plan against active surface-to-air missile batteries, taking advantage of the fact that older, 1950s-era batteries like this one could only engage one target at a time. In addition to Coors flight, Bud flight also consisted of a pair of F-15Es, led by Dodger and Lazarus with Fax and Spidey on their wing. While under separate callsigns, we behaved as if we were a flight of four, with Bat holding the flight lead position. At that time, the Panthers were a well-deployed and highly capable squadron, and the scheduling gods had dealt us a stacked deck of experienced aircrew. While technically very experienced, this was to be the first live combat drop for a number of us, including me.

For the enforcement of the no-fly zone, F-15Es had six air-to-air missiles in three flavors. But just in case, we also carried air-to-ground ordnance: a pair of GBU-12s, 500-lb “Paveway II” laser guided bombs first used in Vietnam. They were reliable, effective, and unpowered, meaning that they had less than half the range of the missile battery we were about to engage. This was like bringing a knife to a gunfight, except that there were many knives, and only one gunman. If one of us were engaged on the way in, the other three would have a clear run. Assuming, of course, that the gunman’s friends stayed out of the fight.

Not a bit interested in a fair fight, we were bringing our friends along anyway. The F-16s (callsigns Devil, Wolf, and Harley), each carried a pair of AGM-88 High-speed Anti-radiation Missiles (HARMs). The high-speed antiradiation missile had proven itself brutally effective in the first Gulf War, riding radar beams down to their origin. The Marine Corps had provided the task force with EA-6B Prowlers, four-seat electronic warfare aircraft with jammers powerful enough to make a hot dog explode, also equipped with HARM. We would need them, because while only one missile battery had fired, there were more with overlapping coverage. We knew about two more missile sites that were occupied, and a third that we should have remembered and didn’t find until a full mission reconstruction — a decade later. The F-15C Eagles maintained a high orbit. In the event that the SAMbush was accompanied by air action, the Eagles would keep hostile fighters off our backs. Devil 01 assembled the overall shot plan on the main frequency while individual flights talked it over on other, discrete frequencies. At 10:23:30z, Devil 01 announced the time over target, and execution began.

Figure 3: “Ghenghis”, one of the 494th Fighter Squadron’s pilots, conducts a preflight inspection of a pair of GBU-12s days after the initial strike. Above her are a 600-gallon fuel tank, an AIM-9 Sidewinder missile, and a hint of the (grey and white) AIM-120 AMRAAM. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Ganging up on a target that can shoot back is not a simple endeavor. Timing is critical. Awareness of the time over target (TOT) is essential to coordinate effects. Just before 10:24z, we armed up and headed in for an estimated time over target six long minutes later. The run-in would last four minutes, starting with a long arcing turn to allow our radar to map the target. Bud flight split off. While we attacked from one direction, Dodger and Lazarus would lead their element from another, thereby coming in simultaneously from different points of the compass. The moment we turned in, Harley ripped off a HARM, programmed to lead us into the target, sniffing for radar emissions. Unnoticed by me at the time, Bat was weaving during the run-in, drawing a snake-like path punctuated with bursts of radar-confusing chaff. It’s one thing to be a target. There’s no reason to be an easy one.

As the guy in the back, my attention was focused on a five-inch, medium-resolution green screen. Laser-guided bombs don’t care what the target coordinates are. They care only where the laser spot is, which meant that I had to find the target and put the crosshairs on it. Our LANTIRN pod, while a reasonably advanced thermal infra-red sensor for the time, was admirably capable of imaging buildings but was rarely sufficient to find and identify small targets. Pattern recognition was key, and the Iraqis had developed a pattern of setting up their missile sites. While roughly adhering to Soviet doctrine, they had their own style. Black dots on a light background can be enough. In the preflight brief, I had briefed each weapons system officer (the backseater) that in the event of an attack, the priorities were the radar, the control van, and the launchers. When in doubt, go for priority one. We had to kill either the radar or the control van on the first pass, or be subject to being shot from behind on the way out. Nobody outruns a missile at close range.

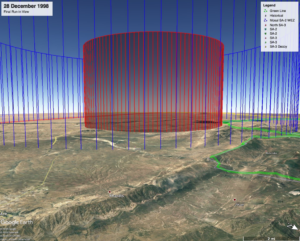

Figure 4: The view from the front seat, or what it would have been if not for the clouds obscuring the ground north of the missile battery. Simulated view from Coors 01 at the beginning of the attack run. The F-15Es would penetrate an SA-2’s envelope (blue) before we got to the SA-3’s (red).

The flights smoked in at around four miles in altitude, just under supersonic speed. We planned on dropping both weapons on a single pass, to raise the probability of kill. I had confidence in the GBU-12s, despite the fact that we had exceeded their (theoretical) airspeed limits in our earlier dash. No radar tickled us on the way in, confirmed by a series of “still naked” calls from the front seat. In theory, I had one eyeball for the image and one eye for the radar warning gear. The problem was that I had only one brain and its optical center was busy. Just as we entered the SA-3’s engagement zone, Devil 01 threw another HARM, this one at the radar we were attacking. This was exactly the challenge a well-executed suppression plan poses for the enemy. The operator must keep the radar off, or risk giving the missile a signal to home in on. Whacker planned to follow Devil’s shot a minute later.

With no target photo to reference, I flipped screens back and forth between the radar image and the targeting pod, matching the pattern spotted on the radar with the image in my scope. Half a minute from our weapons release, the first kink in the plan emerged, with a radio call from Whacker: “Devil, Whacker. No missile.” The HARM’s rocket motor had not ignited, and the missile was stuck on the launch rail, where it wasn’t doing us any good. Harley chimed in with the welcome news that they had a missile inbound, and Bat with a welcome “still naked.” Not that we weren’t committed anyway. We were now 17 seconds from weapons release.

Four seconds before weapons release, I selected my final aimpoint and re-designated, telling the ballistic computer where the ballistic aimpoint was. The radar for the SA-3 (NATO codename LOW BLOW) is unique among older SAM systems in that it is almost 40 feet tall, towering above anything else in an SA-3 battery — so I picked the object with the longest shadow. At the same time we released, Wolf shot yet another HARM at one of the overwatching SAMs, ensuring that our exit was covered. With the 32 seconds it takes the bomb to fall to the surface, my workload dropped precipitously. I had half a minute to guide the weapon in, which consists of keeping the crosshairs on the target and turning on the laser. The bomb would do the rest. Time enough to smoke a lucky, or quote Shakespeare, as the case may be. “Prick us, do we not bleed. Wrong us, shall we not revenge. Ten seconds.”

At 10:29:28z, two GBU-12s turned the radar into hot and rapidly scattering debris, followed two seconds later by a pair of weapons from Bud 02 on the same aimpoint. Coors 02, in accordance with the brief, had targeted the control van (I have no idea how he picked that out), with a release 17 seconds behind us. He switched targets in midflight (also in accordance with the “when in doubt” clause of the brief) to the radar, but the explosions of the weapons from Coors 01 and Bud 02 created so much thermal noise that the laser seekers likely went blind, resulting on a no-guidance, ballistic direct hit on the control van anyway (did I mention there was no wind?). Bud 01, unable to positively identify a target, made the correct choice under pressure and kept their weapons. All four aircraft were across the target in seventeen seconds, which was marvelously well coordinated. After the weapons detonated and I called the impact, I missed everything else that happened to the missile battery afterwards, because my targeting job was done, and it was time to put another set of eyeballs outside to look for other folks doing their targeting job. Fortunately, there were none.

Figure 5: The image right before impact. The radar is under the crosshairs, the control and generator vans down and to the left, and missile launchers at top center and center right.

It was time to leave, and some of the aircraft were low on fuel anyway. As we crossed the Turkish border, I finally took my hands off the handgrips that control our sensors and screen displays, for the first time in 10 or 20 minutes. Freed from the immediate threat, it was only then clear to me via my shaking hands that I was still swimming in the adrenaline backlash. We had a 50-minute flight back to Incirlik, where the news of the first airstrike by F-15Es in the northern no-fly zone was outracing us. There was some relieved humor in the de-arm area after landing, when the Turkish airman tasked with accounting for our weapons came out to check. The idea that we would expend our weapons was clearly one he was unaccustomed to, as he kept walking back between Bud 01, which still had a full load of bombs, and the Coors/Bud 02 trio, which were missing ours.

Later that day, we released the unedited combat tapes to Armed Forces News and CNN, where my mother’s first clue that I was busy happened when she recognized my voice on the tape. Deptula, who had met each aircrew as they shut down engines, took copies of the combat tapes with him and briefed every maintainer, weapon builder, and intel specialist in the task force, to ensure that everybody understood the outcome of their work supporting combat operations. He also altered the rules of engagement again to make it clear that we did not need to ask him for permission to respond to an attack, and that individual flight leads could respond under their own authority. The lethal strikes did not stop because the Iraqis did not stop shooting.

Airpower was the go-to option for both enforcing the no-fly zones and supplying the Kurdish refugees that made the northern zone necessary. It was an effective containment tool that would soon be turned to more tangible effect by dismantling the reconstituted Iraqi air defenses, one target at a time. Eventually, the guys flying in the southern no-fly zone realized we had something, and joined the effort — abandoning a purely defensive posture in favor of a reactive one. A targeted response to aggression evolved into a multiyear campaign that dismantled the Iraqi air defense system (again), starting in 1999. By the time Operation Iraqi Freedom rolled around, the air campaign had been ongoing for four years, and the air defenses were essentially gone. Twenty-one years later, it’s clear that this engagement marked the first round of a resumed conflict, a fact that was not apparent at the time. This probably wasn’t the first confirmed SAM kill by the F-15E, but it was by no means the last. The F-15Es of Lakenheath’s 48th Fighter Wing would go on to kill a dozen or more missile batteries in Iraq and Yugoslavia over the following six months, making the Liberty Wing the most prolific SAM-killer since the retirement of the F-4G Wild Weasel, which was a dedicated radar hunter.

As the 21st anniversary approaches, it is a telling reminder that the U.S. Air Force has been in continuous combat since 1991, the longest combat commitment in U.S. history. That long stretch of continuous warfare has taken the toll on the force, but has also maintained a cadre of aviators with a wide range of combat experience. Hidden in the background, American aviators go into harm’s way daily, largely unremarked upon, using airpower to support the nation’s national security objectives. And sometimes, just sometimes, a major historical turn can hinge on just one small event.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions over Iraq and the Former Yugoslavia during 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Col. Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of US Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the US Government.

Image: Lt. Col. Al “Bat” Cross and Capt. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha await taxi clearance on 30 December 1998 (U.S. Air Force Photo by SSgt. Vince Parker)