Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

A new echelon in the contest for air control has emerged from the maturation and proliferation of affordable small unmanned aerial systems. In 2017, the self-proclaimed Islamic State and forces supported by the U.S. military fought one of the first battles for tactical air supremacy, a contest between sub-$1,000 commercial drones, jerry-rigged jammers, and small arms. While the Islamic State held air superiority below 2,000 feet, the United States and its allies maintained air supremacy above. In Ukraine, Russian separatists and Ukrainian soldiers are fighting a similar contest for tactical air control, but with more sophistication. Russian and Ukrainian innovators, not Americans, have developed a variety of small unmanned aerial systems capable of electronic warfare and strike missions and are pioneering tactics for their use.

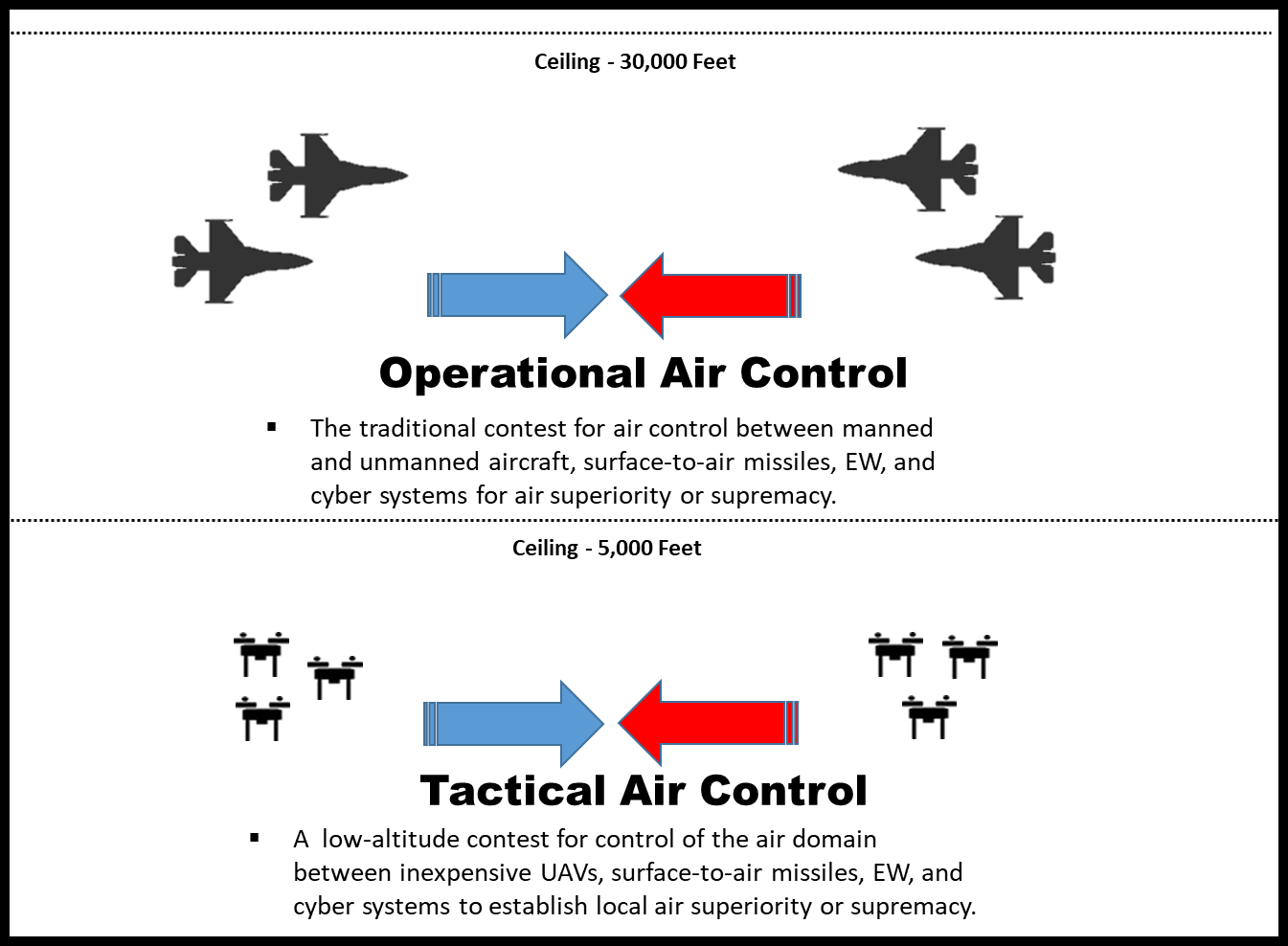

Traditionally, the terms air control, air superiority, and air supremacy have applied to the entire air space, but no longer. The emergence of increasingly capable and affordable small-unmanned aerial systems has begun to democratize access to the air domain and create two echelons of air control: one tactical, one operational. This development offers enormous opportunity to actors unable to contest control of the air space against military powerhouses like the United States, NATO, China, or Russia. Equally, it provides a pathway for modern militaries to increase the supply of airpower assets and efficiently distribute their support to ground and sea forces. For the United States to continue its near-perfect record of achieving air supremacy, the U.S. Department of Defense should do more than invest in counter-unmanned aerial systems technology. It needs to doctrinally define this new level of air control and task a military service, or services, with dominating it in future conflicts.

Tactical and Operational Air Control

The need to divide air control into two echelons derives from capability gaps in fielded systems. Traditional fighter aircraft and air-defense systems have limited abilities to engage smaller unmanned aerial systems. Even if they possessed the ability, the opportunity cost of using an aircraft like an F-35 to engage and destroy a $600 DJI Phantom drone is immense. A single F-35 flight hour costs over 83 times as much as the Phantom. In turn, small unmanned aerial systems have next to no capability to attack or destroy manned fighter aircraft mid-flight. This capability gap and the inefficiencies of using these different classes of assets to engage one another have created two levels of air control.

The U.S. Department of Defense has not defined these two levels of air control, but I propose these working definitions: Operational air control is a traditional competition between air-superiority fighters, air-defense systems, missile systems, and other platforms capable of influencing control of the skies at medium–high altitude. Tactical air control is a contest between less costly unmanned systems, short-

range air defenses, electronic warfare, and cyber systems for the skies immediately above ground forces and ships at sea. Respectively, tactical air superiority and supremacy define the degree of air control possessed at this lower tier, but increasingly important level, of air competition.

Access to the Air Domain for the Poor

Small unmanned aerial systems now allow poorer nations the opportunity to not only defend but also exploit the innate advantages of the air domain — a permanent high ground on the battlefield unencumbered by restrictive terrain. Air power has long been a rich man’s game. Only the wealthiest nations can afford to purchase 4th and 5th generation fighter jets, construct the infrastructure to support them, and adequately train pilots to use them effectively. The acquisition of a single squadron of 12 F-35A aircraft costs nearly $1 billion without added maintenance, ordnance, fuel, infrastructure, crew, or pilot expenses. These severe cost burdens effectively prevent poorer nations from contesting control of the air with a richer power outside of the use of air-defense systems. However, air defenses only restrict an adversary’s ability to control air space. They do not allow the user to exploit it for their own tactical or operational benefit.

Like the iPhone, commercial satellite systems, or the Internet, small unmanned aerial systems are a democratizing technology that provides an effective capability at a fraction of the cost of traditional aircraft. While small unmanned aerial systems cannot rival exquisite, state-produced air platforms, they provide actors a modicum of capability that can shape tactical outcomes and engagements with the potential for operational effect. Small unmanned aerial vehicles have already affected operations in Iraq, Syria, and Ukraine to the point that the commander of U.S. Special Operations Command, Gen. Raymond Thomas, called the Islamic State’s offensive use of drones the most daunting problem faced by special operations forces in 2017.

Continued advances and application of artificial intelligence and machine perception, the development of micro-precision guided munitions and other payloads, and greater performance envelopes (range, speed, ceiling, and lift) will only make the battlefield impact of tactical air superiority and supremacy greater.

Increased Supply for the Rich

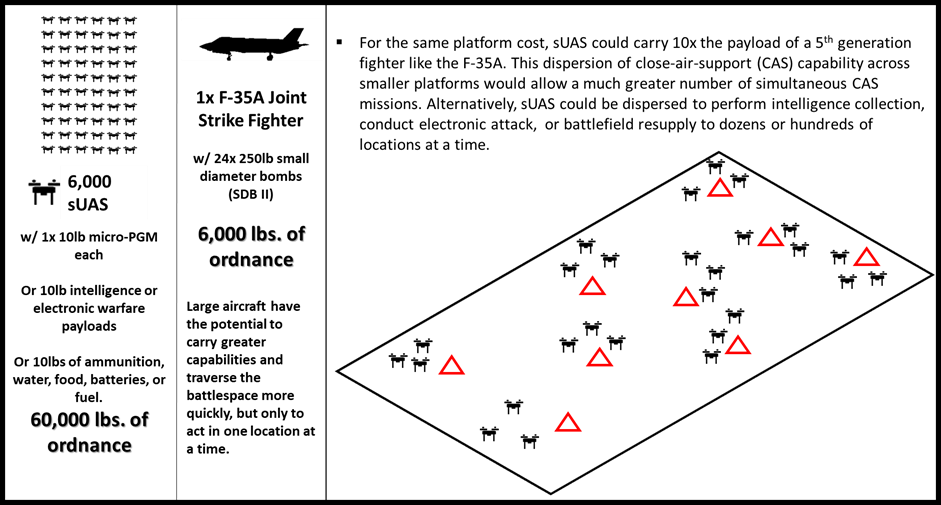

For wealthier militaries, small drones offer avenues to increase the supply of airpower on the battlefield and efficiently apportion it across the battlespace. For the acquisition cost of a single F-35A aircraft, nearly six thousand small unmanned aerial systems ($15,000 each) could be purchased, each capable of supporting a separate element on a battlefield. Although wealthier nations have long had an advantage in gaining air control, they do so at great financial cost. The multitude of expenses associated with creating and maintaining an air force ensures that the number of aircraft available to support ground and sea forces remains limited, creating a situation where demand for air support usually outweighs supply, a scarcity. During the last 40 years, world-class militaries have compounded this scarcity by fielding increasingly expensive multi-role/multi-mission aircraft, which, despite their immense capabilities, can still only be in one place on the battlefield at a time.

Small unmanned aerial systems will never rival the potential capabilities of a manned or larger unmanned aircraft. They cannot carry 500-pound MK82 bombs or transport infantry fighting vehicles like the M1126 Stryker, but they can readily drop 12-pound precision guided munitions, relay line-of-sight communications, or carry ammunition bundles to infantry companies in need. As their independence grows in parallel with enabling technologies, small unmanned aerial systems will gain the capacity to conduct many tactical airpower missions at low cost. Small unmanned aerial systems offer commanders an incredible option to divide and apportion airpower across their entire area of responsibility that manned aircraft cannot match. This is not necessarily swarming (a tactic), but a means of diffusing air-support capabilities to lower echelons.

Who Owns Tactical Air Control?

In 1948, the service chiefs for the Army, Navy, and Air Force met in Key West, Florida to clarify service responsibilities in the wake of the Air Force’s creation. The resulting Key West Agreement reduced Army aviation to reconnaissance and medical transport, allowed the Navy to maintain its combat aviation arm, and gave the Air Force responsibility for the remainder of airpower roles and assets. In the 1952 Pace-Finletter Memorandum of Understanding, Army and Air Force service secretaries agreed to remove weight restrictions from Army rotary-wing aircraft and to permit the Army to employ light, fixed-wing aircraft in support of intelligence, observation, and command and control missions. Finally, in the Johnson-McConnell Agreement of 1966, the Army ceded its tactical transportation aircraft to the Air Force in exchange for primacy in rotary-wing aviation. These three agreements shaped the division of air responsibilities between the military services, but it is time for a fourth.

Department of Defense Directive 5100.01 currently tasks the U.S. Air Force with gaining general air superiority, but the U.S. Army (and U.S. Marine Corps) arguably has the greatest operational need to ensure U.S. forces maintain tactical air control and possess small unmanned aerial systems capable of conducting counter-air, close-air-support, electronic warfare, and resupply missions. The U.S. Army has already fielded a close-air-support-capable switchblade small unmanned aerial system and labeled it a “loitering munition” to avoid Air Force scrutiny. To ensure the United States maintains air superiority at all levels, service chiefs and secretaries should chart out the next evolution of the Key West Agreement. Like the advent of the helicopter before it, increasingly capable small unmanned aerial systems require a rethinking of service dominions. The U.S. Department of Defense needs to clearly define responsibility for control and exploitation of the air domain below 5,000 feet so the United States can continue a near flawless record of air superiority as small aerial drones evolve.

Jules “Jay” Hurst is an Army Strategist (FA59) in the U.S. Army Reserve. He was formerly a member of the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team (Project Maven) within the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence. He has recently published a related article, “Small Unmanned Aerial Systems and Tactical Air Control,” in the Air Space and Power Journal. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

In-article images: Courtesy of Air and Space Power Journal, Vol 33, Issue 1

Header image: U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Julien Rodarte