Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

The Tanaf base in Syria’s southeastern desert had been, in some tellings, a key front in the U.S. campaign to roll back Iranian influence in the Middle East. For one overheated moment, Tanaf was where America would block an Iranian “land bridge” linking Iran to Lebanon via Syria and Iraq. Now the land bridge is a reality, but Washington’s refusal to cede Tanaf is a demonstration of its unwillingness to fold under pressure from Damascus and its Iranian and Russian allies. Tanaf is also, in theory, useful leverage on the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad.

Meanwhile, next to Tanaf on the Syrian-Jordanian border and inside the U.S.-policed “deconfliction” perimeter shielding the base, thousands of displaced women and children in the Rukban camp are hungry. The United Nations has called conditions in Rukban “dire” and warned of another “humanitarian catastrophe in Syria,” warnings I heard echoed in interviews with diplomats, humanitarians, and residents of the camp. The U.S. military regularly moves personnel and materiel in and out of Tanaf, and yet Washington has proved incapable of prevailing on Jordan to allow cross-border humanitarian assistance to Rukban, just south along the border.

Unless Jordan backs down, Washington and its allies have to appeal for cross-line aid provided to Rukban via Damascus, with the go-ahead of the Syrian government. Pending a maybe-forthcoming approval from Damascus, many of Rukban’s estimated 50,000 residents — who include the families of America’s local Syrian proxies and partners — are unable to afford food, lack sufficient medical care, and are unprepared for the coming winter.

America’s involvement in Syria has always been out of step with ground reality inside Syria and in the broader region. Tanaf is no exception.

The reality is the continued U.S. presence in Tanaf is not a show of American determination and strength, or even especially useful leverage on Damascus and its allies. It is an embarrassment, and a symbol of the strategic mess U.S. Syria policy is and has been — a sphere of U.S. supreme military power with no obvious mission, encompassing thousands of women and children Washington can’t convince its closest regional ally to help feed.

Tanaf and Rukban Grow Up Together

The U.S.-led counter-ISIL coalition set up in Tanaf in 2016, in the Syrian-Iraqi-Jordanian tri-border region and next to the eponymous border crossing between Syria and Iraq. The base was meant to reinforce the Jordanian border and serve as a staging ground for an Arab counter-ISIL force trained and equipped by the U.S. and allied special forces. That force was intended to strike at ISIL in Syria’s eastern Deir al-Zour province via Syria’s central Badiyah desert, a southern prong to complement coalition-backed Kurdish-led forces in Syria’s north.

The Tanaf force never grew into something big or effective enough to move on Deir al-Zour. The real death knell for its relevance, though, came after coalition-backed Kurdish advances in Syria’s north in early 2017 and a series of over-ambitious, ill-advised leaks by Trump White House staffers about a proposed counter-Iranian blocking maneuver in eastern Syria pinged Damascus’ and Tehran’s radar. In May, the regime and its Iranian-backed militia allies responded by launching a rapid drive east through Syria’s central Badiyah desert, surrounding and isolating Tanaf.

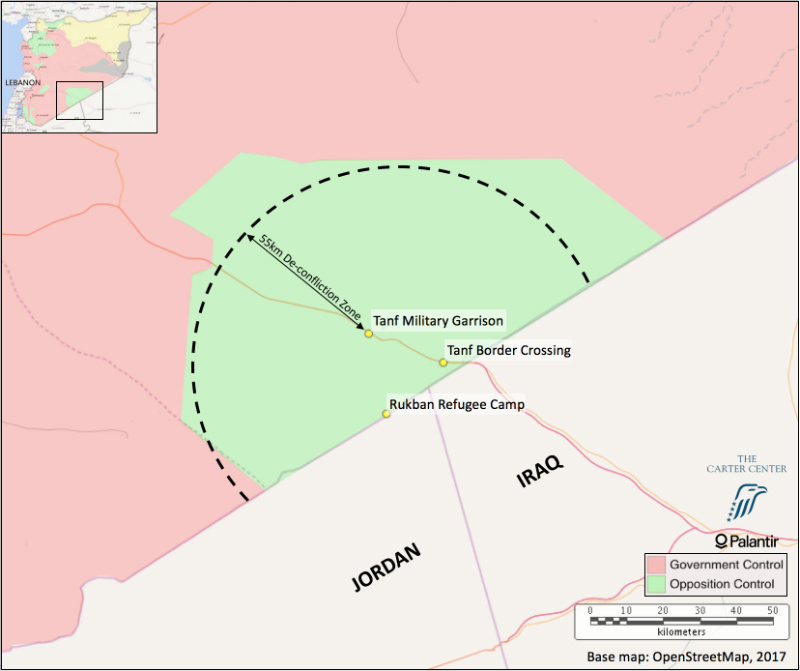

The United States and Russia negotiated a 55-kilometer-radius “deconfliction” to protect Tanaf, an arrangement that — despite some initial incursions into the zone by Iranian-backed militias that were met with U.S. airstrikes — has mostly held. But since the regime’s May advance encircled Tanaf and cut off Coalition-backed forces’ approach to Deir al-Zour, the base and its Coalition presence have been strategically adrift, its counter-ISIL mission defunct. Tanaf is still a training ground for the Arab counter-ISIL unit, but to what end is unclear — the train-and-equip unit has proved impossible to integrate with the Coalition’s Kurdish-led forces elsewhere in the country.

The Rukban camp grew up independently but close by, roughly 16 kilometers (10 miles) southwest of the Tanaf crossing. The camp initially formed in 2013 between the two earth berms marking the Syrian and Jordanian border when Jordan opened and then closed an informal refugee crossing in the desert waste. After Jordan mostly closed the crossing in 2014, it allowed some limited intake of refugees and regular cross-border humanitarian access. But that ended in June 2016, when ISIL drove a car bomb from Rukban and struck a Jordanian border post. Jordan shut the border entirely and cut all humanitarian access before consenting to minimal access on controversial terms.

Tanaf’s 55-kilometer deconfliction zone. Source: The Carter Center, November 2017

Tanaf and Rukban are intimately connected. Earlier this year, rebel-held territory in the Badiyah desert was steadily reduced to just the Tanaf deconfliction zone after a separate CIA-backed rebel force lost the desert areas they had patrolled outside the 55-kilometer line. Those rebels retreated to the 55-kilometer zone, and a smaller camp housing those rebels’ families emptied into Rukban inside the 55-kilometer line. Now the Tanaf deconfliction is all that protects Rukban and these thousands of displaced civilians from the Syrian military and their militia allies, who have dug in around the 55-kilometer perimeter. The Tanaf train-and-equip force’s mission has mutated into securing the Rukban camp, which houses its men’s families and from which much of its rank-and-file has been recruited, as well as patrolling the 55-kilometer zone.

The United States and its coalition partners have taken ownership of the Tanaf zone — they patrol the sky overhead, and their local partners police its edges on the ground. They have not kept Rukban’s vulnerable civilians fed.

Desperation in Rukban

Rukban is inhabited by roughly 50,000 displaced people from across Syria, but largely from the country’s formerly ISIL-held eastern provinces and desert center. And the camp is bleak — an overgrown and anarchic cluster of tents and mud dwellings on a barren moonscape with no infrastructure, agriculture, or real economy.

“I’m not sure ‘camp’ is the right word, to be honest,” said Juliette Touma, UNICEF spokesperson in Amman. “So I’d look for another word — between quotation marks, ‘berm’ or ‘the area between Jordan and Syria,’ but it’s not a camp.”

Since the June 2016 closure of the Jordanian border, Rukban has received one full cross-border distribution of humanitarian aid between November and January and a distribution in May and June that was halted partway during Ramadan. After June, the Jordanian military nixed the military-linked private contractor that had been authorized to deliver assistance in the camp and there has been no new U.N. aid. Jordan pipes water to a distribution area near the camp and permits roughly 100 Rukban residents to cross the southern, Jordanian berm a day to receive medical care in a U.N. clinic before returning to the camp. According to UNICEF’s Touma, an estimated 70 to 80 percent of the camp’s residents are women and children.

Real visibility on camp conditions or reliable statistics on the camp’s population are impossible to come by. Jordan, citing security concerns, has refused to allow international humanitarians to enter to register residents or conduct a needs assessment. UNICEF has conducted a new needs assessment using camp residents it trained but, as of this writing, has yet to release the findings.

What fragmentary information is available about conditions in Rukban is disturbing. U.N. Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Mark Lowcock warned the UN Security Council on 30 October that access to food in the camp is “precarious.” Rukban residents, humanitarians, and diplomats told me the same.

Without cross-border relief, Rukban’s residents have survived on black market goods trucked into the camp from regime or ISIL-held areas. But supply routes have been periodically cut since May, and the markup charged by Bedouin traders on the camp’s northern end prices out Rukban’s poorest and most vulnerable. Camp residents depend on what little money they brought with them, what relatives abroad can send through informal money transfers, or what their sons are paid for serving in U.S.-backed armed factions. Those who cannot scrounge up several hundred dollars monthly for food and who would normally receive humanitarian relief instead go hungry, and the U.N. clinic regularly receives cases of acute malnutrition, including skeletal children. Inside Rukban, large sections of the camp are reportedly deprived, although exactly how many people are in need is unclear. Conditions seem not to have reached the point of actual starvation.

“There’s intense poverty,” said Baraa al-Faris, a civil affairs coordinator working with local U.S.-backed armed factions. “Most residents can’t purchase supplies from the black market at these high prices. Women and children suffer from malnutrition and anemia because of the lack of availability of basic foodstuffs.”

“Starving to death, no — but it’s gotten to a dangerous point,” said Sheikh Muayyad Muhammad al-Obeid, head of Rukban’s refugee affairs council. “A person needs to turn vicious to eat. There’s no work, so where does he go, he needs to eat … Stealing, looting, begging — that what things have come to here.”

Baby formula is also in short supply, camp residents told me, and sharply limited access to healthcare means treatable illnesses are life-threatening. Fuel supplies that had come from ISIL-held Deir al-Zour and had been used for cooking and generators have also been cut.

Winter may be the most immediately pressing concern. “The scariest thing is the coming of winter,” said Muhammad Hadhar Mihiya, a notable from the desert crossroads city of Palmyra now resident in Rukban. “These tents have been ragged for two years. They don’t protect from rain or cold, and the winter here is biting.”

Jordan’s Unyielding Refusal

Jordan has refused to allow a new aid delivery to Rukban. The Jordanians had tentatively agreed to a new delivery this summer but, for unclear reasons, took a hard, uncompromising line after the U.N. General Assembly in September. Jordan has told humanitarians and the donor community that Rukban is a Syrian problem on Syrian territory and insisted that humanitarians develop a plan for cross-line aid delivery from the relief hub in Damascus. That would require a green light from the Assad regime, which has habitually blocked deliveries of aid to insurgent-held areas and instrumentalized humanitarian access as a weapon of war.

“The broader narrative of the Jordanian government is that Jordan has done enough, it’s full,” said a Western diplomat based in Amman who spoke on condition of anonymity. “And donors aren’t doing enough.”

Jordan has already taken on a huge refugee burden, and it has real concerns about its domestic security and stability. It also has reasonable fears about Rukban specifically, which, everyone seems to concede, is to some extent infiltrated by ISIL elements and has been plagued by bombings and other violence. Jordanian officials declined to speak for this article.

Donors’ demands on Rukban have been steadily ratcheted downwards. Jordan totally rejected a late summer push for a new refugee intake from Rukban as the regime and its allies were advancing in the Badiyah. (The push may in fact have soured Jordan on even regular aid access.) Donor demands for hand-to-hand relief delivery at the border and a biometric registration of camp residents were also shot down and have now been abandoned.

What remains on the table is a possible delivery of winterization kits and other relief by crane, in parallel with continuing efforts towards a delivery via Damascus. A crane delivery — done previously in the immediate aftermath of the border summer 2016 closure — is terrible humanitarian practice and, if it started a riot or if the relief was scooped up by powerful local armed factions, would arguably make vulnerable camp residents less secure. But it would at least get supplies into the camp.

It seems dubious that the Assad regime would approve a relief delivery that had to be trucked to Rukban in coordination with U.S.-backed armed factions inside the deconfliction zone, even with Russian and American guarantees. If Damascus did give the okay, it could take weeks or months for aid to arrive. Russia has used conditions in Rukban to needle the Jordanians and Americans in public and in private, claiming the U.S. military in Tanaf and “illegal armed formations” inside the 55-kilometer zone have prevented the Syrian government from organizing humanitarian deliveries to the camp.

Airdrops of relief have been suggested before, but are not currently being seriously considered. An airdrop would be expensive, logistically complicated, and — in terms of humanitarian concerns about a safe, orderly distribution — even worse than a crane delivery.

Jordan may be hoping that the camp just dissipates, as residents are no longer tethered to the Jordanian border by humanitarian assistance and, thanks to “de-escalation” arrangements, are able to return to their home areas. But there is little indication that most Rukban residents are actually willing to leave. Many lack the money to pay smugglers to deliver them through hostile territory — between $300 and $500 a person, residents told me — and their home areas are decidedly unsafe.

“People were considering going to the regime, when there was the national truce in Qaryatein,” said Sheikh Obeid. Syrian government forces recaptured the eastern Homs town of Qaryatein from ISIL in 2016, then lost control again to ISIL in October 2017. By the time they retook the town, ISIL had reportedly massacred more than a hundred civilians.

“People went to Qaryatein, then ISIL came in and slaughtered them with knives,” Obeid continued. “So those who were thinking about going back into the Syrian interior, that idea was wiped out of their heads. They prefer to die here. Eating dirt is better than going back and being slaughtered someplace else.”

Rukban may have actually grown recently, as it has taken in new displaced people fleeing ISIL areas that have fallen to the Syrian government or the Coalition’s Kurdish partners. Without aid, Rukban’s residents may just starve and freeze in place.

Local humanitarians and Western diplomats, including the Americans, have been pushing for humanitarian access to Rukban from Jordan, but with little luck. “There’s a lot of frustration and fatigue on this issue,” said the diplomat. “Unless it can be kicked up to more senior levels, and probably on a collective plane, there’s a sense here we’re not getting traction.”

The United States may be the only country capable of convincing the Jordanians to yield — not using its moral authority, which, on refugees, nearly everyone has forfeited, but because of the vital U.S.-Jordanian security relationship. But America currently has no ambassador to Jordan to make this case, and to do it successfully might require someone much higher up, like the vice president.

The Failure of American Leadership

The United States is unlikely to remain in Tanaf forever, and there is a recognition inside the U.S. government that leaving Tanaf requires a solution for Rukban.

Before some ultimate dispensation for Rukban, however, the camp’s residents need an urgent fix — a delivery of food, medicine, and winterization assistance including tarps and blankets.

Rukban is not like Damascus’s east Ghouta suburbs, a rebel-held enclave deep inside Syrian government territory that is besieged and starved by the Syrian military. Because of UN humanitarians’ limited mandate and Assad’s general imperviousness to outside pressure, it is unclear what America can really do to help Ghouta’s residents. Rukban’s residents are living under similar siege-like conditions, except the encirclement of Rukban is maintained by the United States and its local allies and partners. What’s more, the U.S. military is actually inside this near-siege, based in Tanaf just miles from Rukban. The direct, A-to-B line to providing emergency aid to Rukban runs from key U.S. ally Jordan, just over the southernmost earth berm.

In Washington last month, I was told that a main strut of U.S. Syria policy going forward would be marshalling America’s international and regional allies to isolate the Assad regime economically. That includes blocking reconstruction funds from likeminded Western allies and multilateral institutions like the World Bank, as well as obstructing smaller moves towards economic reintegration, such as the normal resumption of trade between Amman and Damascus through the Nasib border crossing.

America is meant to play a key leadership role in this effort, reinforcing international consensus on an economic blockade of Assad. The idea is to use economic leverage on the regime and its ally Russia, in parallel with diplomatic pressure, to push for a transition and Assad’s removal.

But how is the United States supposed to run herd on its allies in the region if it can’t get the Jordanians to let the U.N. dump aid into Rukban? And how can America plausibly insist Jordan and other allies quarantine the Assad regime when, to keep Rukban’s residents alive, the United States itself has to appeal for cross-line, Assad-approved humanitarian aid through Damascus?

The Rukban-Tanaf situation is another instance where big, sweeping U.S. strategy — moving military and political chess pieces around the Middle East, outmaneuvering dastardly Iranians — runs hard into the reality of the Syrian war, the region, and the international system. In Rukban, there are facts that do not conform to ambitious political projects and that are, for the United States, frankly mortifying. No one is impressed by an invulnerable 55-kilometer sphere defended by the world’s most powerful military that is, on the ground, filled with thousands of impoverished, gaunt women and children.

The U.S. government should first figure out how to drop food, sanitary pads, and tarps into Rukban — now, not at some indeterminate future point when Damascus decides a U.N. aid convoy is politically advantageous. Then Washington can think deep thoughts about regional grand strategy and whose nefarious influence it wants to “roll back” next.

Sam Heller is a fellow at The Century Foundation and a Beirut-based writer and analyst focused on Syria. Follow Sam on Twitter: @AbuJamajem.

Image: UNICEF via United Nations