Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a series. Please read the first installment, “What’s Going On Here?“

Hopefully the last installment helped you stop worrying and love the transatlantic burden-sharing issue, because it’s not going anywhere. If you missed it, I offered a brief historical perspective on transatlantic burden-sharing, and argued the current “crisis” is perhaps not as acute as some have suggested. NATO has even made some tentative progress: From 2014 to 2016, most allies increased defense spending and many transmitted the Wales Pledge guidelines into their national planning. Those actions are necessary but insufficient conditions for achieving the aims it set out at the Wales Summit. What is my basis for suggesting this? It merits a moment’s pause to consider what allies are actually trying to accomplish in this area.

What do NATO allies actually want? To oversimplify a complex idea, each country wants to ensure its territorial integrity and the security of its own population at the lowest possible cost — knowing the interests of each country will likely never be identical to one another. Such an outcome is what I would call the “final” (insofar as anything strategic can be called final) output of defense spending. So, what analysts tend to call “outputs” in the debate about transatlantic burden-sharing are, in fact, intermediate outputs. The assumption is that by having more deployable and sustainable forces alliance-wide, for example, allies will be better able to ensure the territorial integrity and security of their own populations. Since there hasn’t been any variation in the “final” output — NATO has so far managed to defeat communism and prevent any foreign invasions — analysts and policymakers generally rely on inputs and intermediate outputs when discussing NATO burden-sharing.

Since its founding over 70 years ago, NATO has served as a forum for allies to debate and bargain over what resources and capabilities are required to ensure allies’ territorial integrity and security. Part of that debate has always been about who is going to pay for it. The two headline “input” metrics of the Wales Pledge (2 percent of GDP on defense and 20 percent of defense spending on equipment modernization) represent agreement among the allies that what they spend on defense is related to their territorial integrity and security. To put it in clear terms, moving toward spending 2 percent of GDP on defense will make NATO allies more secure. But since the Wales Pledge, analysts have claimed “the idea that NATO capabilities would profit significantly and appropriately from this target is delusive,” and “measuring what the allies spend on defense as a share of their economies tells us nothing about the capabilities they are buying.”

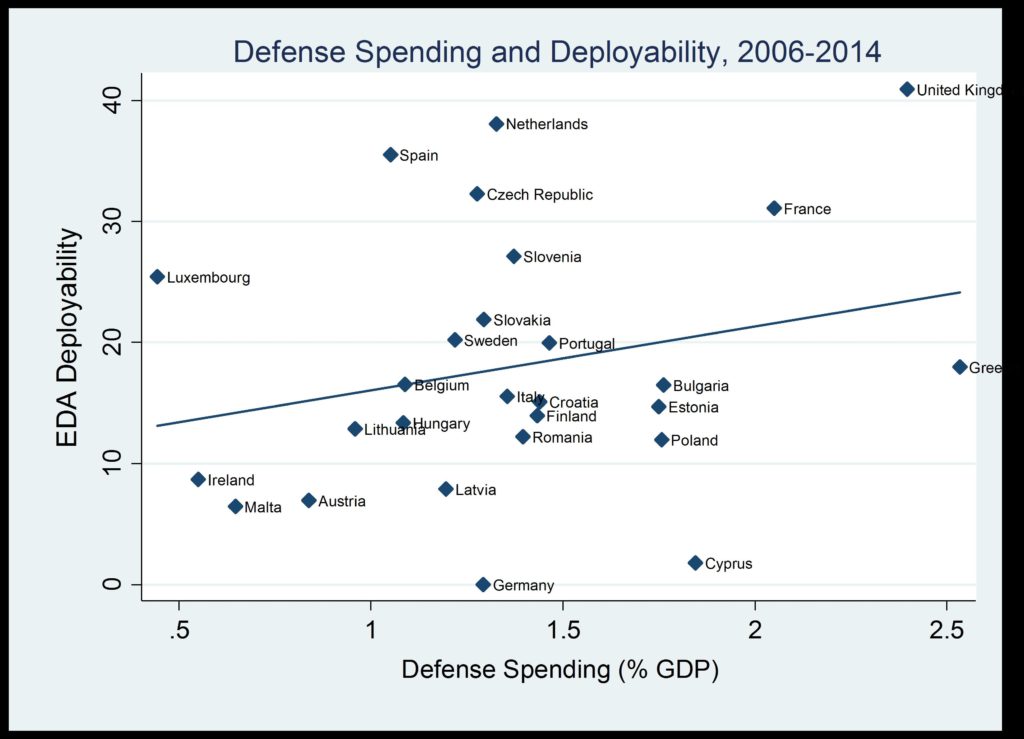

Figure 1: Defense Spending and Deployability. Data Sources: European Defense Agency, NATO, and author calculations.

These arguments are wrong. What NATO allies spend on defense tells us a lot about their capabilities. Consider the scatter plot in Figure 1, above. If I told you the x-axis represented, say, the height of a college basketball player, and the y-axis represented a unanimously agreed measure of that player’s performance over the first three years of his career, would you tell me the height of a college basketball player says nothing about the capabilities your favorite NBA team is drafting? Or that the idea your team would likely profit significantly and appropriately from drafting tall players is delusive or imaginary?

I’ll delve a bit deeper into the data in the next and final installment, but let’s look at how NATO has addressed the issue practically and logically. Allies may never know if the intermediate outputs or capabilities we measure will truly make them safe, but it is clear that spending money on defense helps allies get to the desired intermediate outputs or capabilities. You may not always get exactly what you pay for, but what you get has a lot to do with what you paid.

What does NATO do about this, and what does a seemingly arbitrary number like 2 percent of GDP have to do with it? NATO is probably the most highly institutionalized form of voluntary multinational defense cooperation in recorded human history. Each ally participates voluntarily in the NATO Defense Planning Process (NDPP). This formalized system

is designed to influence national defence planning efforts and prioritises NATO’s future capability requirements, apportions those requirements to each Ally as targets, facilitates their implementation and regularly assesses progress.

Pause and absorb that for a moment — NATO allies actually open up their defense planning books and share them, transparently and systematically, with one another. And they do so on a regular four-year cycle. The current cycle began with NATO allies agreeing in June of 2015 what the NDPP refers to as “Political Guidance”— shared strategic aims and objectives. This guidance outlined NATO’s collective level of ambition for defense and security, defining the “number, scale and nature of operations the Alliance should be able to conduct in the future.” Following that, the NATO Military Authorities produced what they refer to as “Minimum Capability Requirements” (to achieve the agreed level of ambition) and even identified priority shortfall areas in terms of capabilities. This spring, allies completed “Multilateral Examinations,” during which they discussed the assignment of capability targets to each ally. Next spring, another set of examinations will assess the extent to which each ally has made progress in achieving its capability targets.

Multilateral examinations are unique within NATO because they operate on a “consensus minus one” basis. In other words, if an ally doesn’t want to accept responsibility for fulfilling a capability or set of capabilities, it must convince at least one other ally to support its position. Because the allies agreed to “aim to move towards the 2% guideline with a view to meeting their NATO Capability Targets,” it is difficult for a country spending less than 2 percent of GDP on defense to convince another to support it in to avoiding a capability target.

A belief that establishing defense input metrics is useless or irrelevant could be forgiven for those who are not aware of the NATO Defense Planning Process or the relationship between inputs and intermediate outputs. But after this brief conceptual introduction, the stage is set for the next installment in which I examine and interpret some key data.

Jordan Becker is a Defense Policy Advisor at the United States Mission to NATO. This article reflects his views alone, and does not represent those of any part of the U.S. government.

Image: NATO