Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Editor’s Note: This is part of a new series of essays entitled “Battle Studies,” which seeks, through the study of military history, to demonstrate how past lessons about strategy, operations, and tactics apply to current defense challenges.

In the snowy evening of Dec. 5, 1757, a Prussian grenadier sang out the chorus of the hymn Nun danket alle Gott (“Now Thank We All Our God”), and was joined by thousands of voices, as his army gave thanksgiving for one of the greatest battlefield victories of their king, Frederick the Great. The army had just fought a battle outside of the village of Leuthen, in modern Poland. This scene, famously retold across German history, became synonymous with the warrior prowess and military genius of Frederick II of Prussia, as well as the rise of the Prussian state.

The Battle of Leuthen was a critical juncture in the Seven Years’ War and the history of Central Europe. Modern military professionals should care about the battle because the results achieved by Frederick the Great at Leuthen highlight the contingency and dynamism of war. As important, Leuthen demonstrates the dangers of mirroring: assuming that the enemy would react in the same way that we would in a given operational situation. Frederick’s Austrian opponents observed the king’s maneuvers and interpreted them through the lens of what they would do in the same environment. The results were fatal for them, and forged Frederick’s military reputation.

Great Power Conflict in Eighteenth-Century Europe

In early December 1757, it appeared as though, at least in continental Europe, Prussia and its allies had lost what would come to be called the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). A series of hammer blows, delivered in late summer by the French and Austrian enemies of the Prussian King Frederick II, “the Great,” threatened to end the war. Frederick had suffered his first serious defeat at Kolin in June, and his Anglo-Hanoverian allies suffered catastrophe in the aftermath of the Battle of Hastenbeck in July. While Frederick had turned to confront the French, his Austrian enemies had established a base on his territory by taking the fortress of Schweidnitz and smashing the Prussian field army in Silesia at Breslau in November.

The last two developments were especially troubling for Frederick, as they both occurred in the Duchy of Silesia. In Central Europe, the Seven Years’ War was fought for control of Silesia: a vital territory at the intersection between the northern and southern Holy Roman Empire (roughly analogous to Germany and parts of Poland today). Silesia was also an economically important borderland lying between German-speaking Europe and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to the east. Control of Silesia would (barely) vault Prussia’s status into the great European powers with the likes of France, Austria, Russia and Great Britain, while an Austrian-dominated Silesia would ensure that Prussia would never again rise above the ranks of middling powers in Germany: suffering a fate like Bavaria after the Wars of Spanish and Austrian Succession.

Thus, while Frederick II’s army had won an important victory at Rossbach on Nov. 5 over the French and Holy Roman Imperial armies, the future of Prussia hung in the balance as Frederick’s forces retraced their steps back into Silesia in the later part of November and early December 1757. If the Prussian army won the forthcoming battle, it would ensure that the war would go on, with Prussia’s fate still in doubt. If the larger Austrian army waiting for Frederick’s Prussians won the coming fight, at least part of Silesia would almost certainly remain in Austrian hands at the end of the war.

Outflanking the Austrians

By moving forces between theaters and reconstituting forces shattered at Breslau on Nov. 22, Frederick managed to assemble a force of just under 40,000 troops. His Austrian opponent, Prince Charles of Lorraine, had between 50,000 and 55,000 soldiers. The victor of Breslau (though the loser of many other battles), Prince Charles held command by dint of high birth. He had been repeatedly defeated by Frederick in the previous War of Austrian Succession from 1741 to 1748 (Prussia left the war in 1745 but fighting between Austria and France continued until 1748), but his place as (double) brother-in-law of the Austrian Archduchess Maria Theresa had, up to this point, kept him insulated from the consequences of failure.

Frederick, probably the most able royal warlord of the 18th century, was far from a flawless commander, but had rigorously studied generalship for much of his adult life, and had ability, as both head-of-state and field commander (roi-connétable), to take aggressive risks that many other generals refused to take. These risks saw his swift-moving army repeatedly attacking larger enemy forces from unexpected directions: Frequently this led to spectacular victory. Occasionally, it led to equally spectacular defeat.

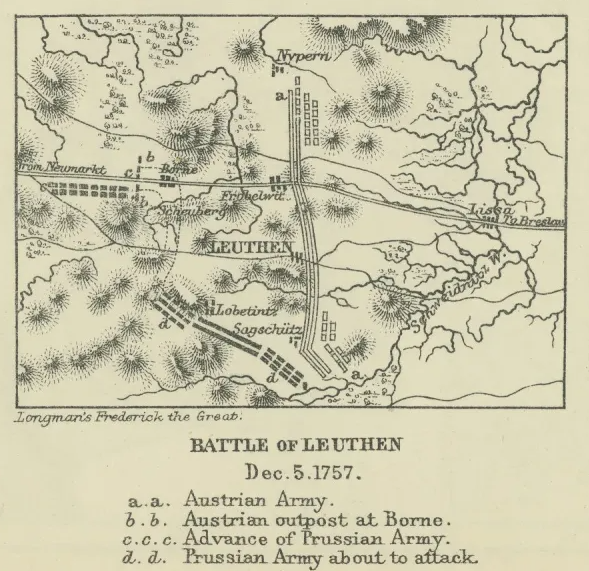

On the morning of Dec. 5th, Frederick directed his army to approach the Austrian position from the direction of Neumarkt from the west and then outflank towards Lobetinz to the south. A feint assault towards the village of Frobelwitz fixed Austrian attention to their front in the center of the line, and then the Prussian army moved off to the south. The Prussian flanking movement was likely visible to the Austrian army, at least at its start: Why did they not move to meet this threat? For every major battle in the mid-18th century, there were multiple “close calls” or non-battles, where one side would approach in battle array, but upon reconnoitering the enemy position, decline to attack, and march off. At Leuthen, Prince Charles and his high command fatally misunderstood the Prussian objective. They believed that Frederick had approached, decided that their partially fortified position was too strong to assail, and then moved off to threaten Austrian communications with the fortress of Schweidnitz to the south.

Frederick’s goal was not enemy fortresses or lines of communication, but his opponent’s field army. As a result, the Prussian force swung its southward march back west and then approached the southern (left) flank of the Austrian position, which was a westward facing line, running south to north. The Prussian army now approached that line from the south — to misuse a naval tactics metaphor, “crossing the T” on the Austrian army. This outflanking maneuver became the hallmark of the battle, commonly associated with the Prussian art of war under Frederick the Great. The Prussian advanced guard of grenadiers and elite regiments quickly overwhelmed the Austrian-allied forces from Bavaria and Württemberg on the southern end of the battlefield, near the village of Sagschütz.

Far from being a quick battle, over in moments with relatively light casualties like the Battle of Rossbach in the previous month, Leuthen was a long and drawn-out affair. The Austrian high command managed to wheel many of the troops from the northern and central part of their battleline into a defensive position around the village of Leuthen. Elite Prussian regiments suffered losses trying to storm improvised defensive positions, like Leuthen’s central churchyard.

While the infantry of both armies contested the village of Leuthen, the only major uncommitted forces were the cavalry wings on the Austrian right and Prussian left. The Austrian cavalry commander, the inspirational Joseph Graf Lucchesi d’ Averna, launched his forces into an attack, hoping to overrun Prussian artillery positions on the Butter-Berg ridge, and attack the Prussian infantry around Leuthen in the flank. If successful, this counterattack would have decided the battle in the Austrian’s favor. However, as a result of intervening high ground, Lucchesi could not see that Prussian cavalry units were waiting to protect the infantry. These Prussians managed to intercept and delay the oncoming squadrons of Austrian heavy cavalry. Lucchesi was decapitated by a round shot, and additional Prussian cavalry squadrons arrived to decide the issue in their favor. With the enemy cavalry neutralized, the Prussian infantry eventually won the contest over Leuthen village and pushed the enemy off the battlefield. Frederick had won what would be considered, justly or not, the greatest victory of his military career.

The Battle and the War

The immediate impact of the battle of Leuthen was significant: For a cost of approximately 6,000 casualties, the Prussians had inflicted about 21,000 casualties on their opponents, including the taking of some 13,000 prisoners of war. To this grim total must be added the effects of Prussian mopping-up operations in Silesia over the next five months: Just shy of 20,000 Austrian soldiers were stranded in Breslau and surrendered as prisoners, and a further 5,000 were netted when the fortress of Schweidnitz capitulated in April of the following year. Thus, the consequence of Leuthen was that almost 50,000 Austrians were lost, the majority as prisoners of war.

Despite this, Leuthen was not a decisive battle: It did not determine the Seven Years’ War, where combat operations would last for another five years, and peace would finally come in early 1763. Leuthen did ensure that Frederick would continue to struggle on. The twin battles at Rossbach and Leuthen saved the Prussian monarchy from destruction. In his recent treatment of the Leuthen, T.G. Otte has (perhaps melodramatically) called the battle “the second foundation of Prussia.” He is probably not far off the mark, in that without Leuthen, the Prussian kingdom would not have survived to become a great power.

It is impossible to summarize the later history of the Seven Years’ War in a short essay, but suffice it to say, there were many Austrian victories and Prussian defeats ahead. Frederick would continue to learn from costly mistakes, changing his art of war to meet the needs of the conflict. Just as he was preparing to give up, Elizabeth Petrovna, the Empress of Russia, died in early 1762. Her death allowed Frederick to focus on his Austrian enemy, winning key smaller battles late in the war, and (once again) liberating Silesia from Austrian control. Out of money and her military resources exhausted, Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria was forced to make peace when the fortunes of war favored her Prussian enemies.

Listen to this episode of The Insider featuring author Alexander Burns by becoming a War on the Rocks member here

Leuthen Through the Years

Like most battles associated with the life and death of nations, the fighting at Leuthen has gone through many stages of interpretation. In the immediate aftermath, Prussian propagandists sought to inflate the number of Austrians present, so that even today, it is common to see claims that 65,000 or more Austrian troops fought at the battle. A more numerous opponent made Frederick “the Great” appear as even more of a military genius than his impressive victories deserved.

On the Austrian side, search for a scapegoat settled in two areas. First, the non-Austrian allied troops (Bavarians and Württembergers) who were deployed in the area of the initial Prussian attack proved to be an easy target for an Austrian military establishment searching to explain away a disaster. Second, Gen. Lucchesi, who had died while leading his troops into action, was quickly selected as a convenient bugbear for the loss. This can be seen in the often-quoted memoirs of the Prince de Ligne, a junior officer in the Austrian service at the battle: “we ought never to have listen to Lucchesi … the few Württembergers who did not run away surrendered … the Bavarians departed a few moments later.” Despite his efforts to remain in command, Prince Charles of Lorraine was unable to fully deflect blame for the disaster, and he left the army in January of 1758. His fall coincided with the rise of a new generation of Austrian military leaders, who inflicted severe defeats on Frederick in the following years of the war.

As the 18th century gave way to the 19th, Frederick’s victories became the source of a north German nationalism that emerged before, during, and after the Napoleonic Wars. After an ambiguous position in the post-Napoleonic era, Frederick and Leuthen took the place of a foundational myth as Otto von Bismarck fought a series of wars and paved the way for the unification of Germany under Prussian leadership in 1864,1866, and from 1870 to 1871. The battle, and particularly the singing of the hymn, Nun danket alle Gott, by troops immediately after the battle, took on profound spiritual and national significance. Paintings of the battle, the singing troops, and the king became widespread in the Kaiserreich period. With Germany’s entry into and defeat in World War I, Leuthen remained at the heart of German identity. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Battle of Leuthen took on new life in a new medium: film. Over a dozen films, in which Frederick II was almost always portrayed by actor Otto Gebühr, tried to captivate the public with the Frederician era. A particularly patriotic installment, Der Choral von Leuthen, which focused on the battle, premiered four days after Adolf Hitler assumed the chancellorship of the Weimar Republic. With the popular memory of Leuthen being closely tied with the Nazi regime, popular depictions of Frederick and Leuthen became much more infrequent, even and especially in Germany, after the horrors of the Holocaust and World War II.

Lessons of Leuthen

Leuthen remains a relevant subject for military study in the 21st century. The battle is an important reminder of the contingency of military events. A noteworthy tactical success, Leuthen brought strategic benefits for Prussia. The British government, forced into the embarrassing convention of Kloster-Zeven, repudiated this agreement in the face of Prussian victories and provided Prussia with substantial military aid for the rest of the conflict. This prevented French armies from decisively intervening against Prussia. The money that British subsidies provided enabled Frederick to continue the grim struggle for survival that characterized the Seven Years’ War after Leuthen.

Leuthen, then, demonstrates how an unexpected battlefield victory can galvanize and change international relations and diplomatic affairs: perhaps like the success enjoyed by the Ukrainian armed forces in the days immediately after the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022. Stories of heroism and stoicism of a head of state in danger can shift international opinion, be they Frederick and Leuthen in 1757, or Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Hostomel Airport in 2022.

Leuthen is also a powerful lesson that a victory, even one that feels decisive, does not always bring about enemy collapse and the end of war. The British public became deeply enamored with Frederick in the aftermath of Rossbach and Leuthen, but slowly consigned him to a place of irrelevancy and criticism as a quick victory failed to materialize. Indeed, a spectacular and unexpected victory can build up expectations in a way that makes the usual reality of attritional warfare seem almost like a defeat.

For military professionals, the fighting at Leuthen shows the dangers of mirroring and assumption in strategic thinking. Practitioners should be cautious when they assume that we “know” what the enemy is doing or going to do. The Austrian high command at Leuthen assumed that their Prussian opponent was moving to the south to threaten their communications with Schweidnitz and force them from a favorable defensive position. It is what they would have done, so they assumed that Frederick would do it as well. After the battle, an Austrian officer reported that, “Everyone believed he was marching towards Schweidnitz.” This mirroring led to complacency in the face of an unexpected attack.

Finally, Leuthen provides a space to think about the role of command. Freed by his role as roi-connétable, Frederick could accept prudent risk and launch operations against numerically superior opponents in defensive positions. He was uniquely able to overcome a problem that was endemic among army commanders in his period: caution and indecision. Austrian Gen. Lucchesi also took initiative and accepted prudent risk in launching his cavalry counterattack. Sometimes, the difference between a commander who is praised for the next 250 years and one who is scapegoated and then forgotten is as thin as the imprecise flight path of a cannonball.

Alexander S. Burns is an assistant professor of history at the Franciscan University of Steubenville, studying George Washington’s army and its connections to European militaries. His recent book, Infantry in Battle, 1733-1783, was published in 2025. You can follow him @KKriegeBlog.

Image: The collections of Sanssouci Palace, Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg via Wikimedia Commons