The Islamic State Stopped Talking About China

In July 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the now-deceased leader of the Islamic State, named China first in a list of 20 countries and regions where “Muslims’ rights are forcibly seized.” Al-Baghdadi specifically cited the “extreme torture and degradation of Muslims in East Turkistan,” the name for the Chinese province of Xinjiang used by Uighur separatists. Over the following three years, the Islamic State continued its outward support for and recruitment of the Uighurs in a string of video, audio, and print propaganda.

The culmination of Islamic State advocacy for the Uighurs came in a February 2017 video featuring Uighur foreign fighters training in Iraq and pledging to shed Chinese “blood like rivers to avenge the oppressed.” This was the group’s first direct threat toward China, and experts cited it as evidence China had become “very firmly a target of jihadist rhetoric.” Soon after, in June 2017, the Islamic State announced it had executed two Chinese teachers abducted in Pakistan’s southwestern Baluchistan province.

Since these provocative actions in 2017, however, the Islamic State has almost entirely ignored the plight of the Uighurs, according to my analysis of a broad swath of subsequent Islamic State publications. Additionally, I found no further claims in the group’s media to have followed through on threats to attack Chinese interests, and no reports of such attacks in international media.

This apparent decision by the Islamic State to de-emphasize China’s repression of Uighurs, a mostly Muslim ethnic group of 11 million that China fears harbors extremist views and is attempting to “re-educate” in detention camps, is at first hard to square with the Islamic State’s self-appointed role as violent defender of Muslims everywhere. The Islamic State’s inattention carries significant risk to the organization. Much of the Islamic State’s success in attracting and maintaining support across the globe has been born from its willingness to take extreme action to match its extreme worldview. Growing anger in many Muslim-majority countries over the lack of support for the Uighurs from their religious and political leaders — many of whom have been cowed by Chinese investment — is a golden opportunity for the Islamic State to recruit.

However, the Islamic State seems to have determined that a less provocative approach to China is more advantageous. Specifically, the group believes an unprovoked China can play a constructive role in achieving an overriding objective: ending the U.S. military presence in the Middle East and South Asia.

The Enemy’s Enemy

The Islamic State rightfully recognizes China as the greatest enemy of its greatest enemy. The Islamic State also recognizes that Beijing’s “peace through development” approach to expanding its influence in the Middle East and South Asia, whatever its longer-term negative implications, is useful in the short term vis-à-vis the jihadists’ conflict with the United States.

China’s emphasis on using commerce rather than military intervention to increase its influence has allowed it to forgo a significant military presence in the Middle East and South Asia, while capitalizing on economic opportunities that undermine the reliance of regional powers on the United States. This arrangement leaves the burden of security, particularly counter-terrorism, to Washington — a fact that has irked both Republican and Democratic presidential administrations. This lopsided arrangement also creates pressure for the United States to “right-size” its presence in the region, military-speak for “bring troops home.” Domestic incentives for the United States to lower its regional military profile, and a corresponding increase in China’s less threatening, mostly economic influence, is likely a welcome development from the perspective of the Islamic State.

The Islamic State endangered these favorable strategic trends by highlighting an issue as sensitive for the Chinese government as its treatment of Uighurs and its perceived threat from domestic extremism. Following the Islamic State’s February 2017 video featuring Uighur fighters, China’s Foreign Ministry called for greater international cooperation on counter-terrorism. Some U.S. observers even speculated this could lead to joint U.S.-Chinese efforts to defeat the terrorist group. Sino-American cooperation and burden sharing around the common threat of terrorism is not what the Islamic State wants. It is much better that bilateral relations remain uncooperative and zero-sum. Likewise, it is in the Islamic State’s interests that China continues to pour cash rather than troops into the region, and it is better that the United States, unsure why it is investing so much military energy into a region with wavering partners and intractable problems, continues to eye the door.

Going Quiet

The Islamic State has most likely abandoned its aggressive stance toward China for these strategic reasons. To preserve the useful dynamic of a non-militarized China replacing a militarized United States in the Middle East and South Asia, the Islamic State appears to have abandoned its previous advocacy and adopted a near total, systematic silence on not just the Uighur issue, but also Chinese influence more broadly.

Figure 1: Screenshot from the first, and last, Islamic State propaganda video featuring Uighur-speaking fighters.

Source: Wilayat al-Furat Media, Feb. 27, 2017 (jihadology.net).

In a thorough review of the Islamic State’s videos, magazines, and more than 190 issues of its long-running newsletter, Al-Naba, published since the February 2017 Uighur threat video, I found only one explicit mention of the Uighurs and only a single page dedicated to China’s rising influence.

This inattention was further reflected in a partial collection of more than 500 “Daily Harvest” documents I assembled since October 2017. These documents, shared online by the group’s supporters, serve as daily roundups of official Islamic State media output, including reporting by the Amaq News Agency. Not a single document contained a mention of the Uighurs, or even of China.

The only explicit mention I found of the Uighurs in troves of Islamic State media published since February 2017 appeared in the July 2020 issue of the group’s Voice of Hind magazine (Hind being a shortened form of Hindustan, i.e., India). Feeling compelled to dismiss the significance of the years that had passed since last mentioning the Uighurs by name, the Islamic State claimed, “Uighur Muslims are not hidden from us, neither are we indifferent towards their cause.”

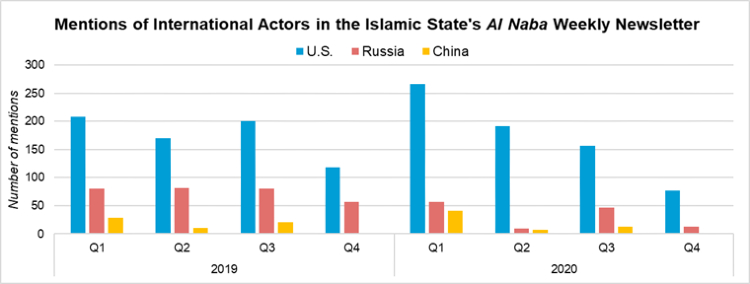

Figure 2: Al Naba Analysis

Source: Generated by the author. Q4 2020 data ends on Nov. 29, 2020.

A lexical analysis of 99 issues of Al-Naba published between Jan. 1, 2018, and Nov. 29, 2020, demonstrates the extent to which the Islamic State has extended its silence to all aspects of Chinese influence. Most notably, the outlet has mentioned by name China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the trillion-dollar investment project with the potential to reshape the Middle East and South Asia, exactly once.

Overall mentions of China in Al-Naba during this period trailed mentions of the United States by a margin of more than 10-to-1. In part, this reflected the publication’s attention to militant activity targeting U.S. interests. But more revealingly, when China has appeared in Al-Naba, it has almost never been as an adversary in its own right. Rather, China appears as a rival to the United States, such as in coverage of the deterioration in U.S.-Chinese trade relations and flare-ups between the two great powers in the South China Sea.

Hypocrisy and Projection

However, while the Islamic State’s lack of attention to rising Chinese influence has been consistent, it has not been absolute. Amid its conspicuous and disciplined pattern of omission, the organization provided one fleeting glimpse of its true feelings toward China in February 2019. On a single page of an issue of Al-Naba, the organization laid out the negative dynamics of growing Chinese influence from the jihadist perspective. The group warned its followers that China is using “the method of investment” to “strengthen its ties with tyrannical governments” and predicted that “it will not be long before [the Chinese] intervene [in the Muslim world] directly through war with soldiers, aircraft, missiles, and warships.”

In a brazen display of hypocrisy and projection, the writers of this outlier article also attempted to foist the Islamic State’s own strategy onto the organization’s jihadist competitors, accusing “those who claim to belong to the jihad” of avoiding discussion of “despotic Chinese rule [and] the crimes they’ve perpetrated against Muslims” in order not to “open a new front in the jihad that they’d prefer remain cold so as to [keep fighters and resources] available for the fight against America.” The article also contained the organization’s first direct threat toward China in two years, calling on Muslims “to wage war against the idolators of China everywhere” with “killing and capture … seizure and sabotage.”

However, the Islamic State’s propagandists then reverted to silence in subsequent issues of the newsletter, saying nothing as China took dramatic steps in subsequent months to strengthen ties with Iran and Saudi Arabia. I found no specific mention in the organization’s media of moves to finalize a $400 billion Sino-Iranian strategic partnership said to include significant security cooperation, nor of recent indications Beijing could be helping Riyadh develop nuclear weapons. The possibility that the Islamic State’s propagandists failed to notice these events is hard to believe given their own warnings about China’s regional strategy and the extent to which the group regularly discusses less consequential developments related to these regional adversaries.

There is also no indication that the Islamic State has done anything to fulfill the article’s call for terrorist violence against China. I found no reports in international media of the Islamic State or its supporters perpetrating attacks against Chinese interests anywhere in the world since, and the organization has made no claims of doing so. Meanwhile, the group has boasted about its commitment to perpetrating and inspiring attacks in Africa, Europe, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. The outlier February 2019 article was clearly the exception to the rule.

Perhaps the clearest example of this rule, which allows the Islamic State to wage jihad against a global cast of Muslim “oppressors” while conspicuously omitting China, came in a video released on July 26, 2020, by the group’s premier video production outlet Al Hayat. The video, titled “Incite the Believers,” called on “all Muslims, in every place, under the rule of any sect of disbelief and apostasy” to wage domestic terror attacks. The video unsurprisingly featured the United States as its primary enemy before going on to suggest Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Germany, Turkey, France, Canada, and Egypt as appropriate targets. But there was no mention or even suggestion of China.

Figure 3: Screenshot from the Islamic State’s “Incite the Believers” video production featuring some of the countries it encouraged its followers to target.

Source: Al Hayat media, July 26, 2020 (jihadology.net).

Fundamentals

Despite admitting it harbors concerns about the long-term implications of China’s rise in the region, the overriding reality for the Islamic State is that the United States today maintains 60,000 troops in the Middle East while China does not. The estimated 2,000 troops that China is believed to have deployed at its inaugural overseas military base in Djibouti do little to alter this fundamental imbalance.

The Islamic State further understands that an unprovoked China is deeply uninterested in taking on the responsibilities of regional security provision, even in a post-U.S. regional order. However, there is no guarantee the United States will make fundamental changes to its Middle East strategy. The attempts by successive U.S. administrations to “get out” of the region have failed, and the Donald Trump administration’s most recent effort to reduce U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan will still leave thousands in both countries, with tens of thousands more at nearby bases.

China’s growing ties to regional states and its newly attained status as the region’s largest and most sought-after investor have also not gone unnoticed in Washington. U.S. analysts and military commanders are warning of a threat to the longstanding U.S.-dominated regional order posed by China’s rise in the Middle East and South Asia. Even if the United States is weary of its involvement in the region and feeling the pressure to pivot military resources to Asia, the Joe Biden administration will not be eager to risk regional oil supplies and trade routes falling into the hands of China or other rivals.

Ultimately, a complete U.S. military exit from the Middle East and South Asia remains a long shot. However, even a significant U.S. drawdown will be a boon for the Islamic State so long as it is replaced by China’s more hands-off approach. A more multipolar region is a region that is less willing and less able to root out extremist actors.

If achieving that more permissive environment means ignoring the plight of the Uighurs, the Islamic State is on board for now.

Elliot Stewart is a Middle East analyst and the 2020 Young Professionals in Foreign Policy Counter Terrorism fellow. His areas of expertise include state-controlled media strategies, extremist propaganda, and Shia militia groups.

Image: Voice of America