Discovering Soviet Missiles in Cuba: How Intelligence Collection Relates to Analysis and Policy

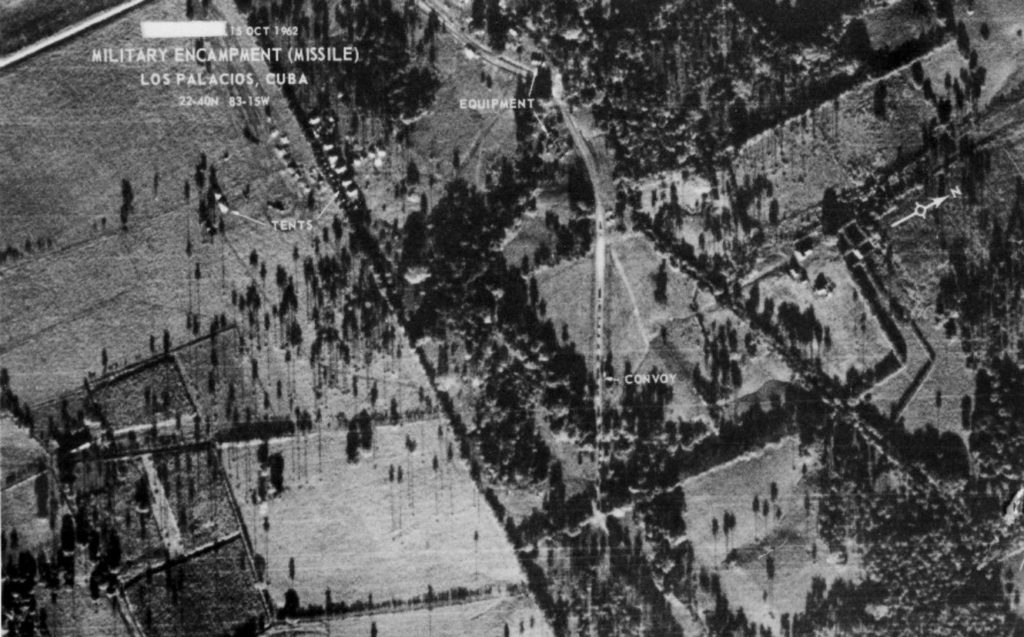

Fifty-five years ago this week, a lone U-2 spy plane soared over western Cuba, taking 928 photographs of the island 72,500 feet below. Analyzing these images the next day, photo interpreters at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) identified SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles deployed outside the town of San Cristobal. National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy informed President John F. Kennedy of the deployments the following morning.

Too often, the story of U.S. intelligence and the Cuban Missile Crisis is told from this point forward. The movie Thirteen Days, for example, opens with a montage of a U-2 flight and photo interpreters poring over black-and-white film reels and finding the missiles. In such accounts, American intelligence collection was comprehensive, persistent, and effective, implying discovery of the missiles was inevitable. Quite to the contrary, however, the United States failed to detect the secret operation to install Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba for nearly six months. The medium-range ballistic missiles were actually in Cuba five weeks before U.S. intelligence discovered them. While the intelligence community counts the missile crisis among its historic successes, it might be considered more of a near-failure, as multiple scholars have noted. Many have mined the missile crisis for lessons regarding political decision-making, estimative intelligence, and critical thinking. Yet intelligence collection remains a relatively unexplored angle of the case. What did we know, when, and by what means? This essay considers just how the missiles were discovered and the enduring implications this holds for intelligence collection and its relationship with analysis and policy.

Operation ANADYR

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev decided on a bold move in May 1962: fulfill Cuban requests for military aid (following the CIA’s failed Bay of Pigs operation) by sending tanks, aircraft, air defense equipment, and, crucially, five regiments of medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Cuba. He hoped this operation, codenamed ANADYR, would improve the credibility of Russia’s nuclear deterrent, provide a rhetorical response to recent U.S. intermediate-range ballistic missile deployments in Turkey, and demonstrate solidarity with Russia’s newest client state. Conceived personally by Khrushchev and predicated upon secrecy, ANADYR was known only to select Soviet political and military leadership.

Though a sizeable military operation — thousands of pieces of equipment and tens of thousands of personnel moving 8,000 miles, making 200 trips beginning in June 1962 — ANADYR presented a series of challenges for U.S. intelligence collection. Imagery (IMINT) and signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection inside the USSR itself was limited and sporadic. U-2 IMINT was no longer viable over the USSR after the May 1960 shoot-down of Francis Gary Powers. Corona photoreconnaissance satellites provided valuable but infrequent coverage and lacked the frequency and resolution to identify missile regiments departing garrisons or ANADYR cargos being loaded in Soviet ports. SIGINT largely involved radio-frequency intercepts from platforms outside the Soviet periphery. The USSR was, with one or two notable exceptions, a non-permissive environment for human intelligence (HUMINT) collection: the closed nature of Soviet society and extensive counterintelligence measures made traditional espionage extremely difficult. For these reasons, U.S. collection entirely missed the opening stages of ANADYR.

Moreover, ANADYR was one of those intelligence problems often found in movie scripts but rarely seen in real life: a secret plot. Spy fiction frequently revolves around such plots: adversaries pursuing complex secret plans, many months in the making. Fictional intelligence officers uncover such plans by taking the right photograph, decrypting the right communication, stealing the right document, or interrogating the right person. Yet real-world problems rarely take this form. As intelligence luminary Gregory Treverton famously describes, intelligence problems may be thought of as puzzles (knowable secrets) or mysteries (future developments which can only be bounded or framed, never definitively known). Typical intelligence collection is postured to address typical problems: small puzzles, like military operations masked by standard operational security or terrorist identities masked by false names, or big mysteries, such as the intentions of foreign leaders or major political developments. Collection is usually not equipped to deal with big puzzles: rare instances of secret plots like Pearl Harbor, the October 1973 surprise, 9/11, and ANADYR. When you don’t know you’re dealing with a secret plot (as you won’t if the plotter is any good), intelligence collection won’t be optimally postured to discover the threat, and limited resources will be dedicated to other priorities. In the spring and summer of 1962, there was no American embassy in Cuba and the few American HUMINT sources there were focused on regime stability, state security, and socioeconomic issues, as well as supporting covert efforts to topple Castro.

Secret plots also allow adversaries to employ extensive denial and deception. A highly complex maskirovka effort accompanied ANADYR. Operational knowledge was compartmentalized and tightly restricted. Soviet personnel took steps to avoid American SIGINT, minimizing sensitive communications and writing them down or passing them verbally when necessary. Crews camouflaged sensitive equipment while underway and loaded and offloaded only at night, behind secure perimeters with high walls. To throw the Americans off the trail with false indicators, some crews were issued Arctic gear, and the very name of the mission was meant to convey some connection to the Anadyr region in the Soviet Far East. The Soviets even lied to their own ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, who served as an unwitting (and highly effective) deceiver.

Rumors and speculation regarding possibly nefarious Soviet activity on the island further complicated U.S. collection. Such churn confused the intelligence community’s understanding of actual activity without adding any real information. As one 1964 post mortem noted, U.S. intelligence received more than 200 HUMINT reports regarding atomic weapons and ballistic missiles in Cuba prior to January 1962 — months before Khrushchev even conceived of ANADYR. Speculation about missiles in Cuba also occurred in public. Following the Bay of Pigs and Berlin blockade crises, Republican politicians and pundits pointed to acknowledged Soviet military activity in Cuba as evidence of Kennedy’s failure to prevent Soviet aggression on America’s doorstep. One public discussant took matters even further: on Aug. 31, Sen. Kenneth Keating (R-N.Y.) claimed there might be Soviet rocket installations in Cuba. On Oct. 10, Keating claimed “six missile bases” were present. Pressed for details by Director of Central Intelligence John McCone, Keating refused to cooperate. Whatever the source of the senator’s claims — reliable, real, or otherwise — their partisan nature further drove many in Kennedy’s cabinet to question and dismiss the notion of Soviet offensive missiles in Cuba.

SNIE-85-3-62, The Photo Gap, and (Delayed) Discovery of the Missiles

On Sept. 19, the CIA published the now-infamous Special National Intelligence Estimate (SNIE) 85-3-62, “The Military Buildup in Cuba.” This estimate is often cited as a woeful example of entrenched mindsets, groupthink, and mirror imaging bias. The SNIE concluded there was no clear evidence of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba and that the Soviets probably would not deploy such weapons. To be fair, for all its analytic failings, the first part of the SNIE was correct so far as collection was concerned: as of the estimate’s drafting deadline, no IMINT or SIGINT had detailed the arrival of such weapons. No accurate HUMINT reporting detailed their presence until after the SNIE. Before mid-October, IMINT and SIGINT were ambiguous about the broader nature of the Soviet buildup. The buildup was clearly large in scope and scale. Yet every data point — arrivals of aircraft, cruise missiles, surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and the overall spike in secretive military cargos arriving in Cuban ports with incomplete or false manifests — was equally consistent with either 1) Soviet claims these were conventional military shipments meant purely for Cuban self-defense or 2) fears by individuals like McCone that the buildup might contain nuclear weapons. (Later, this and similar experiences drove the intelligence community to develop structured analytic techniques to surface hidden assumptions about the meaning of collected data.)

Unlike IMINT and SIGINT, some HUMINT — from Cuban émigrés debriefed in Florida and clandestine sources inside Cuba — offered reporting explicitly claiming the presence of offensive missiles. As one collector noted shortly after the crisis, sources claimed seeing “large intercontinental rockets more than 20 meters long” and “many mobile ramps for intermediate-range rockets.” While these reports seem alarming in retrospect, at the time, they were relatively rare among the larger body of reporting and only processed after CIA wrote the SNIE. Additionally, they came from sources with little vetting or reporting records.

Yet despite the need to continue monitoring the buildup for evidence it might possibly include such weapons, on Sept 10 Bundy and Secretary of State Dean Rusk directed future U-2 flights to avoid Cuban airspace to dodge the recently discovered SAMs — disregarding protests by IMINT representatives that this would cripple collection over central Cuba. For the next five weeks, this decision resulted in a so-called “photo gap” wherein the IMINT representatives’ concerns were vindicated: none of the four missions flown during this period covered the island’s interior because of the flight path restrictions. Administration officials were only pressured to resume flights over the Cuban interior on Oct. 9 in the wake of concerns by McCone and Defense Intelligence Agency leadership over mounting HUMINT reporting of missiles in western Cuba. This resulted in the fateful Oct. 14 flight and NPIC’s discovery of the missiles.

Enduring Implications

As this case highlights, collection platforms and sources are themselves political devices and actors whose peculiarities, limitations, and risks shape how intelligence is produced. The implications of this case are enduring because they reflect basic realities of human nature and political behavior.

Successful collection requires complementary coverage from multiple disciplines. This is the conclusion that the modern intelligence community has arguably taken most to heart. Multiple sources are essential for production of accurate, comprehensive intelligence. Eventual discovery of the missiles was only possible through cross-cued, multi-INT collection. SIGINT failed to provide independent proof of an offensive buildup, but identified increased maritime shipments and unusual communications, drawing further attention. HUMINT justified overturning the “photo gap” restrictions and cued the IMINT flight that ultimately revealed the missiles. In turn, while IMINT provided the “smoking gun,” imagery analysts benefited from HUMINT-derived context: technical details of Soviet missile airframes and field deployments provided by a spy, Soviet Colonel Oleg Penkovsky. Such collaborative, multi-INT collection is a hallmark of modern intelligence operations.

Despite being frequently depicted as sequential steps, collection, analysis, and policy are in a constant state of interaction and backflow. As others have noted, the notion of a sequential “intelligence cycle” is deeply flawed. In the months preceding discovery of the missiles, the intelligence community published an analytic assessment that the Soviets wouldn’t install such missiles even as it pushed for increased collection to look for said missiles. Policymakers hamstrung this collection request based on analysis that, in turn, suffered from insufficient collection. A politician, perhaps aware of classified reporting on the issue, shaped the debate over collection and analysis by publicly making it a partisan political issue.

Geographic proximity is no guarantee of useful collection. Satellites could overfly the USSR and Cuba with impunity, HUMINT sources were available inside Cuba, and SIGINT collected information from a variety of sources around the world. Yet none provided the necessary diagnostic information. While a Corona satellite mission did image western Cuba on Oct. 1, it lacked sufficient resolution to identify the missile sites and poor weather conditions made matters worse. Though present in Cuba, clandestine HUMINT sources tackled a plethora of competing priorities and lacked sufficient vetting and collector confidence. While SIGINT was collected both at sea and inside Cuba, effective Soviet communication security and encryption forestalled any SIGINT-derived reference to “missiles” or “nuclear” activity.

Intelligence consumers receive data from non-intelligence sources that compete for attention and confidence. Conversations with Dobrynin and Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, press speculation, and politicized rumors all shaped policymakers’ and intelligence professionals’ understanding of reality. The issue even appeared in popular culture. Graham Greene’s 1958 novel Our Man in Havana and its movie adaptation the following year revolved around false rumors of foreign weapons deployments in Cuba and spies’ gullibility in falling for such rumors. It is no great leap to imagine that this is where CIA and DIA analysts’ thoughts might have turned when seeing HUMINT reporting of powerful weapons deployed on the island.

Today, Russia’s emphasis on information operations that similarly eat away at the fabric of evidence-based analysis is well-established. As various outlets have noted with regard to Russian efforts to shape perceptions regarding Crimea, MH17, Syria, and other issues, it is highly effective to simply flood news outlets and social media with counter-narratives and anti-Western cynicism. Russia often benefits from extant rumors and conspiracy theories. Such efforts may overwhelm any evidence-based narrative drawn from intelligence collection, undermining our understanding of threats and attribution.

Intelligence collection does not occur in a policy vacuum. Collection is an inherently political act, with the potential to drive developments as well as inform them. As the shoot-down of a U-2 at the peak of the crisis on Oct. 27 illustrated, intelligence collection is not a passive research function. It is an act of statecraft that invariably carries risks. In turn, policy realities either enable or inhibit effective collection. The Eisenhower administration’s strong support for developing technical intelligence made possible the very existence of the U-2 and the operations that allowed U.S. intelligence to find the missiles. Yet Eisenhower also closed the embassy in Havana, which crippled HUMINT collection. The Kennedy administration’s reluctance to risk another international crisis essentially blinded U.S. collection to the presence of the missiles for five weeks. Even before the “photo gap” decision, the administration made clear the political sensitivity of potential Soviet offensive deployments. We see today decisions where sensitivity and risk aversion result in self-imposed collection constraints, which in turn risk the kind of collection blinders that nearly forestalled discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba.

Intelligence success during a crisis requires effective collection prior to the crisis. It is possible to increase or revise collection during a crisis; however, agencies must constantly collect, catalog, and disseminate baseline information to prepare for these events. Details of Soviet equipment — required to detect them and inform policymakers of their capabilities — were acquired many months before the crisis via Penkovsky, attaché reporting, and technical collection by overhead imagery, radioactive sampling, seismographs, and ground-based radars. The intelligence community could not simply request and collect such knowledge ad hoc once nefarious activity was suspected. NPIC’s archives and knowledge of targets, built from years of U-2 and Corona coverage, were essential for analysts to quickly and accurately identify equipment in Cuba. SIGINT had previously gathered and cataloged communications frequencies and radar emissions, allowing analysts to locate and characterize activity. Conversely, HUMINT’s limitations in Cuba posed a serious problem.

This might be termed the Intelligence Codicil to Murphy’s Law: Major crises will occur in the countries near the bottom of the collection priority list. It remains as true today as in 1962: Decisions to refocus collection efforts and operations carry real risk. Because collection is inherently a zero-sum game — there are only so many aircraft, sensors, case officers, and antennas to go around — this will remain an enduring challenge for intelligence collection.

Though 2017 is a very different time for intelligence collection than was 1962 — given today’s multipolar world filled with diverse threats and a globally networked, public information environment — there are insights we can take away from this seminal event 55 years ago. While intelligence collection platforms and methods inevitably change with the passage of time, the interplay between collection, analysis, and policy described above will endure. We would be foolhardy to ignore the hard-won lessons of the (admittedly last-minute) discovery of Soviet nuclear missiles deployed 90 miles off our shores.

Joseph Caddell is the Arthur C. Lundahl Chair of Geospatial Intelligence at the National Intelligence University in Bethesda, MD. The views expressed in this article are his alone and do not imply endorsement by the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Image: National Security Archive