After more than 40 years, the Dartmouth class of 1967 has come to terms with the Vietnam War. That understanding has come after a long effort to bury our past — a past dominated by what historian David McCullough called “the longest and most unpopular war in which Americans ever fought.”

For several decades after Vietnam, my classmates and others who were scarred by the war largely refused to discuss, much less confront, our memories of fighting the war, fighting against the war, avoiding the war, making tough life decisions because of the war, and facing disdain from those who made other choices.

Our class, and those males who graduated from college in the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s, faced a host of diverse ghosts from a war that was highly controversial at the time and is now almost uniformly seen as a foreign policy blunder.

A key moment in this confronting of our past came in June 2017, at a symposium on the Vietnam War organized by the Dartmouth class of 1967 at its 50th college reunion. The symposium, which lasted 3 ½ hours, was as much a chance for classmates to discuss their own feelings (then and now) as to hear from others. We were bearing witness to our unique era, but one whose lessons may be valuable to today’s young men and women and those in future generations.

***

Beirne Lovely spoke to the assembled classmates about his experience as a 2nd lieutenant during one of the most notorious battles of the war against the North Vietnamese Army in Khe Sanh. A platoon-sized element of his unit was assigned to an outpost outside the perimeter of the main base. The outpost was attacked and virtually overrun by what was estimated to be more than a battalion of North Vietnamese regulars. The marines suffered many casualties during the battle, Lovely recalled.

Upon Lovely’s return from Vietnam, no one greeted him at the airport. He and his fellow marines were looked upon with scorn and there were, of course, no welcome-home parades.

Lovely said that in retrospect, he has come to the regrettable conclusion that the war was a mistake. In an emotional recounting, he explained that he had come to better understand and respect the motives of those who strongly objected to the war at the time. Nonetheless, he told the crowd, “All of that said, I’m damn glad I served.”

The crowd rose to give Lovely a standing ovation.

Three speakers later, Andy Barrie described a very different experience. In April 1966, he had an epiphany after listening to a speech by draft board director Gen. Lewis Hershey. He went from apolitical to deeply opposing the war.

After graduation, Barrie was drafted by the Army. He trained at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, to be a combat medic. When he received orders to head to Vietnam, he deserted and fled to Canada.

Barrie still lives in Canada, where he has established a very successful radio-broadcasting career. He has received the Order of Canada, the country’s highest civilian honor, for his broadcasting work. He told the crowd that crossing the border was the first day of the rest of his life: “I became as good a Canadian as I would have hoped to become a good American.”

This symposium was the first time Barrie had discussed his war experience with an American audience because he had feared that those who served and fought would find his story insulting.

For the second time that day, both classmates who served and who protested joined to stand and applaud a classmate with a very different experience than Lovely’s, but who also stayed true to his principles.

***

In fact, the more than 800 members of the class of 1967 had been working toward this moment for decades. When we entered college in 1963, Vietnam was a low-grade conflict in Southeast Asia, and few were even aware it was underway. By the time we graduated in 1967, it had become “our war,” the war that changed the directions of our lives then and in each of the 50 years since.

Previous classes of graduates, when confronted with war, could be sure they were fighting for a noble cause supported by most of the country. Our soldiers helped turn the tide in World War I, defeat the Nazis and Japanese in World War II, and beat back the North Korean invasion of the South. They came home heroes, even if they wanted nothing more than to get on with their lives.

It was very different in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The war became increasingly divisive among classmates and in the entire country, turning friend against friend, children against parents, and citizens against leaders. Many served proudly, only to return home to little support if not outright hostility for participating in the war. They discovered that the cause that they had signed up for, to prevent Asian “dominoes” from falling into Communist hands, had turned into one of the major geopolitical disasters in American history.

The cost was high, with the names of 58,000 Americans chiseled on black granite in Washington, D.C. Many more struggled with lost limbs or mental challenges, a disease with no name at the time but now called post-traumatic stress disorder. They had seen carnage and death but, it turned out, for little purpose. Soldiers got meager assistance from the U.S. government in transitioning from military to civilian life. The Veterans’ Administration provided only minor help.

As a result, there is little wonder most of our classmates wanted only to bury their experience in Vietnam. These Americans had participated in the first war that the United States had ever lost.

Moreover, the war constricted the choices faced by young men in that era. Today’s 18-22-year-olds don’t face the same pressure from local draft boards or a national lottery. They can make choices about school, training, travel, employment, and family without facing the specter of being forced to serve.

In time, most of my classmates, even those who were gung-ho to serve at the time, came to accept that the war was wrong and a major strategic mistake.

***

While I was in college, I gradually moved from skepticism about the war to outright opposition and protests. Yet in the background was the ever-present pressure of the draft board.

I may have come to despise the decisions of Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon and General William Westmoreland. But in 1968 my draft board said it was time to take an Army physical — a prelude to being drafted.

The State Department came to my rescue, in a fashion: If I agreed to go to Vietnam as a civilian joining the pacification program, I would not have to fight.

Pacification was a combined military, CIA, State Department, and USAID program to win, in the vernacular of the day, the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people over to “our” side. The program, like the war effort, was a dismal failure.

I served in Vietnam for 13 and a half months, mostly working with refugees. I also quietly, unbeknownst to the authorities, worked with American reporters to provide information from within about the lies and misguided policies.

One month, a province in my area received the highest rating for security according to one of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s many metrics of success. But I learned at the same time that an American military advisor had contradicted this assessment by writing in a confidential report to his superior that the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong controlled the night there. With my help, that information became a newspaper story, adding – I hoped – to official and public skepticism of an increasingly futile war effort.

Still, I recognized then and still feel that I had made a deal with the devil about which I was uncertain in 1969 and remain uncertain in 2017. I avoided bitter warfare and may have even helped a few refugees, but I had entered into the belly of the beast to become a small cog in the “green machine.”

***

In 1992, 25 years before our 50th milestone, some class members joined an impromptu discussion of Vietnam. It was clear that we were talking about a long-repressed subject.

Based on those and other discussions, we decided to hold a symposium on the Vietnam era at our 50th reunion, as well as to put together a book about our war-related experiences.

After Lovely’s and Barrie’s speeches, many others stood to describe what they went through in the late 1960s. Jon Feltner was wounded twice while serving two tours in Vietnam. Fifteen minutes after he took command of his first Marine infantry platoon, he recalled, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong launched the 1968 Tet Offensive throughout South Vietnam, including a mortar attack on his platoon.

Feltner made a pilgrimage to Vietnam in 2010 as part of his rehabilitation and faced the ghosts of long ago. Returning to one of the places where he was wounded and his unit lost 27 marines, he chanced to encounter a Vietnamese man who had also fought that day, but for the Viet Cong. The two held a joint memorial service for Americans and Vietnamese who lost their lives in that battle. Feltner said that no matter what we experienced individually in the Vietnam War, as a generation, the era was the most “intense” period of our lives.

As a young boy, Warren Cook wanted to join the Marines, and he did. He arrived in Vietnam in January 1969, six months after his college roommate and hockey teammate Bill Smoyer was killed in An Hoa Province.

During Cook’s 13 months, he served as a platoon commander in the northern part of I Corps as a psychological operations officer and a general’s aide. The concept of post-traumatic stress wasn’t developed until later. But Cook had survivor’s guilt, along with disturbing memories and anger about how he was treated upon his return to the United States. He buried those memories, used alcohol as a crutch, and lied about what he did in Vietnam.

In an essay he wrote for the reunion book, Cook wrote, “It took me 30 years to begin to write about my time in and experiences after Vietnam. And, it took another 10 years to translate those notes and ramblings into something coherent.”

Like Feltner, Cook went back to Vietnam to grapple with his past. In September 2015, 47 years after he served, Cook returned to the Ho Chi Minh trail. Those whom he had once labeled Viet Cong, Charlie, or “gooks,” he now called freedom fighters. An especially emotional moment came when one of his guides, the son of a North Vietnamese artilleryman, presented Cook with his father’s NVA veteran’s pin. Cook has now become involved in a nonprofit that helps clear the unexploded ordnance that continues to claim victims in Vietnam.

Classmate Paul Beach had an altogether different experience. He refused to go to war and helped organize the “We Won’t Go” union to resist the draft. He was involved in many protests, including the May 1969 Parkhurst Hall takeover at Dartmouth protesting the war and the presence of ROTC on the campus. For that, he received 30 days in the Merrimack County, New Hampshire jail.

That was just a precursor: A few months later, he spent two years at the minimum security prison in Allenwood, Pennsylvania for refusing to serve. At any given moment during his time in prison, there were about 25-50 secular draft resisters plus 30 Jehovah’s Witnesses who also declined to fight. “I’m very fortunate that I don’t have the level of guilt that many have had to suffer,” Beach told the audience. He feels the war was not just a “mistake,” but a part of a broader, problematic pattern of U.S. foreign policy.

Other classmates discussed their difficulties coping with their war experiences. Cai Sorlien continues to suffer. He served in a detached battalion of the Air Cavalry and felt almost totally ignored by headquarters. He pointed out that true unit cohesion, which his group lacked, “helps to absorb a lot of the shock and horror and terror that combat is.” Comparing his situation to today’s war on terror, he remarked, “We were terrorists. I was a terrorist. That was part of my job.”

Douglas Coonrad was an Explorer Scout in high school and active in the Dartmouth Outing Club. He entered the Navy ROTC and flew jets. Coonrad explained to our class, “I have no doubt that I’m still suffering from post-traumatic stress,” but added that he thinks he has handled it.

He reminded us of the impromptu and highly moving discussion about Vietnam at our 25th reunion: “That was the first time many people opened up and told us things that they had not told their families.” He added that this symposium, along with an interview he did for the Dartmouth Vietnam Project, were cathartic, forcing him to think about what he did during the war and what lessons he learned from it.

It was evident that classmates had very different views about their actions during the Vietnam War. One was proud of his military service, one compared himself to a terrorist, one served in prison but bore no guilt, one crossed a border into an entirely new life, and one had survivor’s guilt. But while each one came to terms with the war in his own way, and there were many different beliefs and experiences, after 45 years, all respected each other’s choices.

***

Phil Curtis summed up the feelings of many about the era: “The options were not clear; the decisions were not easy. But no matter what route any one individual took during the period of the Vietnam conflict, it affected them personally, their family, their friends, and their loved ones. Not all came back, and many of those that did were the worse for the wear.”

John Isaacs served in the pacification program in Vietnam for 13 and a half months. Since returning in 1972, he has worked in Washington, D.C., including almost 40 years at Council for a Livable World, as a lobbyist and analyst of national security issues such as nuclear weapons, defense budgets, arms control and overseas military interventions.

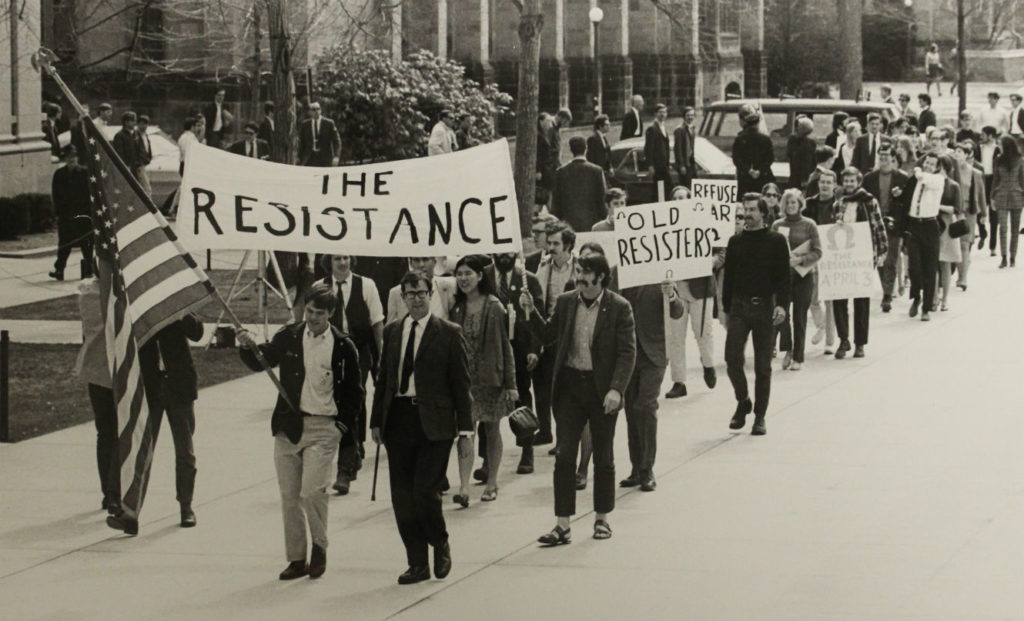

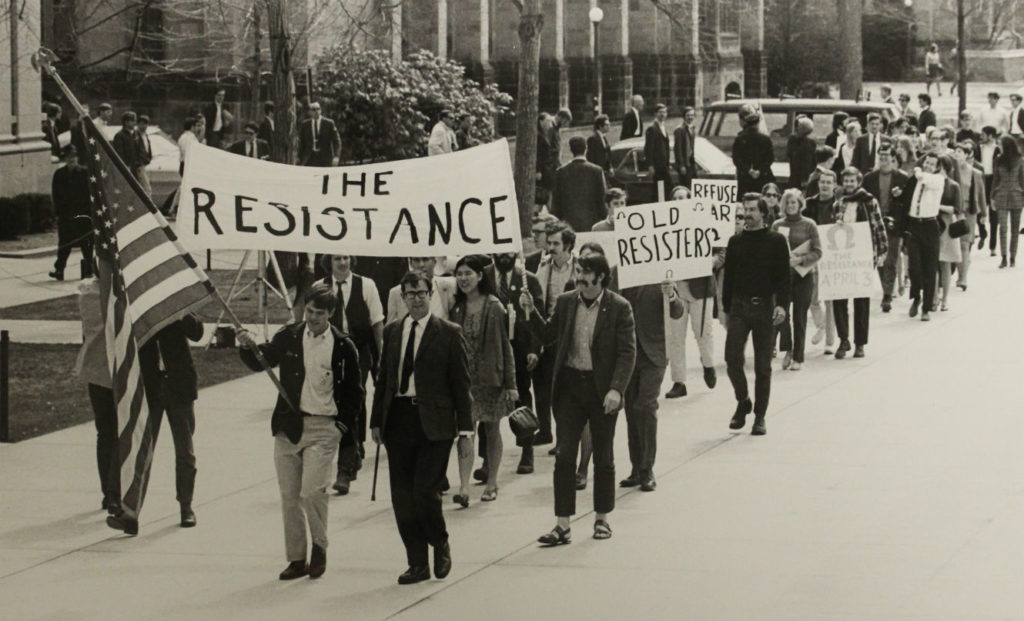

Image: National Archives