Editor’s Note: Welcome to the ninth installment in our new series, “Course Correction,” which features adapted articles from the Cato Institute’s recently released book, Our Foreign Policy Choices: Rethinking America’s Global Role. The articles in this series challenge the existing bipartisan foreign policy consensus and offer a different path.

In 1998, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright told Matt Lauer on NBC’s Today Show: “If we have to use force, it is because we are America. We are the indispensable nation. We stand tall. We see further into the future.” Albright’s view was anything but unique to her or to the Clinton administration. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a strong bipartisan consensus in favor of frequent American military intervention has reigned in Washington. Even President Obama, who came into office calling for greater restraint than his predecessor, expanded the “war on terror,” engaged in regime change in Libya, and extended the mission in Afghanistan – America’s longest war. Facing vocal critics who seek to increase American intervention not just in the Middle East but also in conflicts throughout the world, Obama was unable to implement many of the more restrained policies he advocated.

The American public, however, is far less supportive of an interventionist foreign policy agenda than political elites. Given this, a critical task for the next president will be to navigate between the interventionist tendencies of the right and the left, while embracing the “restraint constituency.” An analysis of polling data from both CNN/ORC and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs reveals that this constituency, which cuts across party lines and represents roughly 37 percent of the public — exhibits a reliable disposition toward foreign policy restraint, opposing the use of military force in all but a few cases. That contrasts with an “interventionist constituency” that represents about a quarter of the public and supports much more aggressive efforts to promote American interests abroad. Since neither constituency’s core followers represent a majority, the deciding voice between intervention and restraint in foreign policy debates belongs to the 40 percent of the public that falls somewhere between the two camps.

Though the restraint constituency enjoys an advantage on many important foreign policy issues, public fears about terrorism and other global conflicts will continue to be a significant challenge for restraint-minded policymakers. Framing world events as “other people’s business,” reminding the public of the costs of major war, and pursuing an active noninterventionist counterterrorism strategy can help policymakers encourage public support for a more restrained foreign policy.

The Restraint Constituency

In the broadest sense, most Americans agree that the United States should play some sort of role in world affairs. The most commonly asked poll question on this topic asks whether the United States should “take an active part” or “stay out” of world affairs. The proportion of respondents who say “take an active part” has ranged between 60 percent and 70 percent since the mid-1980s. What such surveys do not communicate clearly, however, is what exactly people mean when they answer them. In the case of military intervention, taking an “active part” could mean anything from contributing to a peacekeeping mission to frequent full-scale regime change of a hostile regime, while “stay out” could mean anything from cutting ties with allies to rejecting responsibility for resolving foreign conflicts.

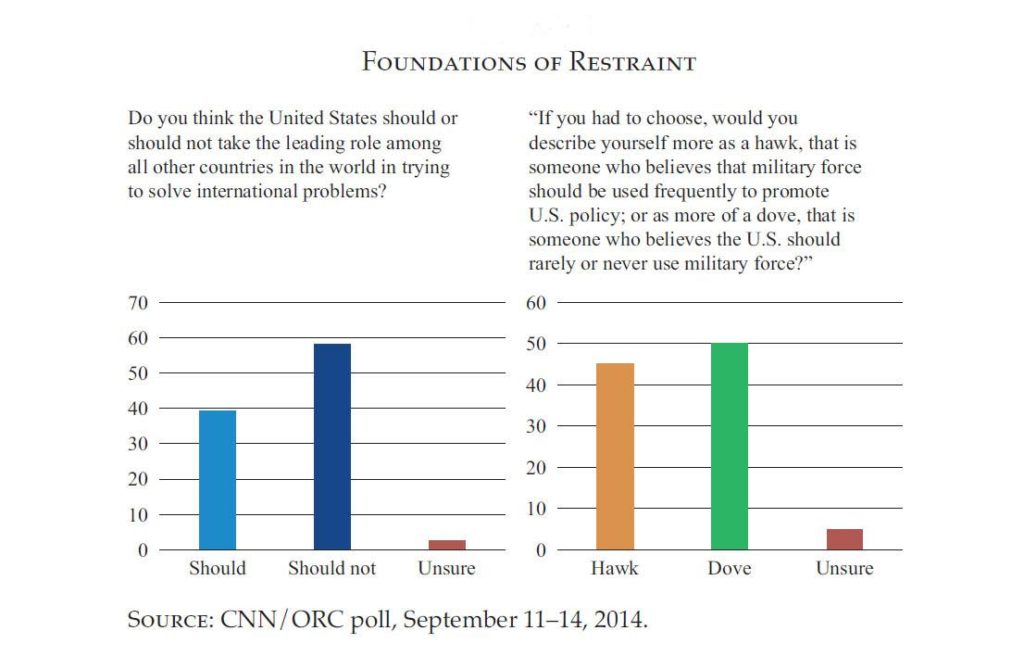

We can develop a more complete picture by assessing people’s beliefs on two key fundamental questions regarding intervention and the use of force. The first question concerns how much effort the United States should make to solve the world’s problems. The second concerns how often the United States should turn to military force to promote national interests. Figure 1 provides a snapshot of Americans’ underlying attitudes along these two dimensions.

Fig. 1

With these answers in hand we can begin to identify competing predispositions towards foreign policy. Some Americans – those we label here the restraint constituency – feel that the United States should not seek to take the leading role among all nations to solve the world’s problems. They believe that the United States should rarely use military force. The interventionist constituency, on the other hand, are those who answer the opposite. This group believes the United States should take the leading role and support the frequent use of military force to promote American interests. Figure 2 combines responses to both questions, helping identify and measure four distinct postures toward foreign affairs.

Fig. 2

These predispositions toward restraint and intervention are just that — under certain conditions, even restrainers will support intervention and interventionists will not. At any particular moment, Americans’ opinions reflect not only these predispositions but also information coming from political leaders and the news media about the world. More recent polling on the Islamic State, for example, illustrates that support for an aggressive response has risen considerably across all groups as concerns about the threat posed by the Islamic State have grown.

The Politics of Restraint Today

The shifting context of international security and domestic politics provides both opportunities and challenges to policymakers trying to chart a restrained path in foreign policy.

Today, three major factors work in favor of restraint. The first is war fatigue. Large majorities remain convinced that both the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were mistakes. With over 7,000 U.S. military personnel killed and many thousands more wounded, and trillions of dollars spent killing terrorists and “exerting influence” in the Middle East and elsewhere, many Americans are simply convinced it is time to spend more time focusing on domestic concerns. A 2016 Pew survey found, along these lines, that 70 percent of the public wants the next president to focus on domestic issues compared to just 17 percent who want to see a focus on foreign policy. One possible interpretation of this finding is that a growing number of Americans may see little connection between military intervention and American security, especially given how few terrorist attacks have occurred on American soil since 9/11. As a result, fewer may now believe such efforts are worth the high costs in lives, money, and in the lack of attention paid to domestic issues. Such poll findings establish a high burden of proof for future intervention. Those seeking to repeat a troop-intensive intervention in the Middle East not only will have to explain why the security risk justifies such an action but also must reassure the public that the next Islamic State will not emerge in its aftermath.

Second, the American public continues to find serious military intervention justified in relatively few situations. As surveys from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs repeatedly illustrate, a majority of the public opposes most potential uses of U.S. ground troops, with two key exceptions: humanitarian intervention (including preventing genocide) and preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons. The emergence of the Islamic State also represents a significant challenge to a restraint-minded president. The group’s barbarism, along with the attacks in Europe, San Bernardino, and Orlando, have driven public support for an aggressive response to levels not seen since the early days after 9/11, though support for sending American troops remains low.

Finally, looking beyond the temporary effects of global events, the situation today reflects generational shifts in public opinion. The data reveals that the restraint constituency has been growing as younger and less intervention-minded Americans start to replace older, more interventionist Americans. The Millennial generation, born between 1980 and 1997, is the most restrained yet, with both Democratic and Republican Millennials more likely to fall into the Restraint Constituency. Figure 3 illustrates the generational shift toward restraint.

Fig. 3

The Road Ahead: Priming the Restraint Constituency

Continued clashes between the restraint and interventionist constituencies are inevitable. Both camps can rely on a core of followers to support their positions and both have illustrated the ability — on different issues — to command majority support. The key questions thus become under what conditions will the restraint constituency win the day? And how can policymakers help make that happen? Restraint-minded policymakers can make the strongest case possible in various ways.

Most important, policymakers should assert a “civil conflict” frame when discussing the situation in places like Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and any future failed or troubled state. Historically, the restraint position has been most compelling when Americans believe they are being asked to intervene to resolve other nations’ internal problems, while interventionist arguments have been strongest when Americans are asked to take action against a group or nation that poses a direct threat to the United States. In reality, of course, public perception often depends in large part on how the president, other political leaders, and the media frame that issue in the first place.

The Syrian civil war provides an excellent illustration of this dynamic. In 2013, the popular perception was that, although tragic, the situation was above all a civil war and primarily Syria’s problem. As a result, 68 percent of the public told pollsters that the United States did not bear responsibility for Syria. A similar majority opposed sending troops or even providing aid to the rebels fighting Assad. Yet by 2015, a large percentage of the public saw Syria not only as a civil war but as a battlefield on which to confront the threat of terrorism, largely thanks to the attacks in Paris and San Bernardino.

Restraint-minded policymakers should also invoke the length and cost of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, along with the chaos that both created, including the birth of the Islamic State. Even as Americans indicate a desire to move more aggressively against the Islamic State, they remain extremely wary of a full-scale ground war. To the extent that political leaders can keep the public focused on the dangers of any military engagement, they can reduce the appeal of calls for more intervention.

Finally, policymakers, especially the president, should emphasize noninterventionist strategies for counterterrorism. It is clear that the fear of terrorism is the most likely cause of future American intervention abroad in the near to medium term. And though nothing can completely eliminate calls from the interventionist constituency to play whack-a-mole abroad to combat terrorist groups, the majority of the public traditionally prefers exploring nonmilitary means of solving problems to the use of force. By highlighting an active program of nonmilitary counterterrorism efforts, the next president could blunt calls for military intervention.

Looking ahead, the greatest danger to the case for restraint is the interventionist habit of America’s political leaders. Under either a President Clinton or a President Trump, it seems extremely likely that the United States will continue to suffer from what Christopher Preble calls the “power problem.” Thanks to the exceptional security and overwhelming power the United States possesses, it enjoys too great a temptation, to intervene abroad in pursuit of all kinds of foreign policy goals that have nothing to do with national security.

Trevor Thrall is senior fellow at the Cato Institute and associate professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

Image: U.S. Navy Photo by MC3 Laurie Dexter