Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

In the 2014 movie Edge of Tomorrow Tom Cruise’s character has a bad day. And like Bill Murray in Groundhog’s Day, he has to live it over and over again. Yet instead of trapped in a charming Pennsylvania town, Lt. Col Bill Cage has to relive an assault on the beaches of France reminiscent of D-Day, but with aliens instead of Nazis. Another crucial difference between Operation Overlord and Cruise’s day from hell is that he and his comrades are outfitted with a range of exosuits – wearable technologies externally conforming to the human body and augmenting human abilities.

While exosuits have been a mainstay of fiction for decades – you’ve perhaps read about them in Starship Troopers, seen them in Iron Man, or even played a character wearing one in Halo or Call of Duty – they have also been the goal of real U.S. military efforts for nearly as long. Yet despite the ground-combat focus of both science fiction and science research, combat is not the only useful application, and land not the only environment in which they can operate. Intrigued by ambitious talk of the future of TALOS, SOCOM’s powered exosuit project, a colleague and I set out last year to instead look at the potential uses of and designs for exosuits in maritime operations, culminating in a report just released by the Center for a New American Security.

One of the first things we found is that some of the most promising near-term exosuit uses in maritime operations are some of the most mundane: performing maintenance, deck operations, and logistics functions like taking on stores. To put it simply, completing physically demanding tasks such as line-handling or overhead grinding. In this sense, the future of maritime exosuits is likely to be more akin to Sigourney Weaver’s powered work loader from Aliens than Tony Stark’s Iron Man.

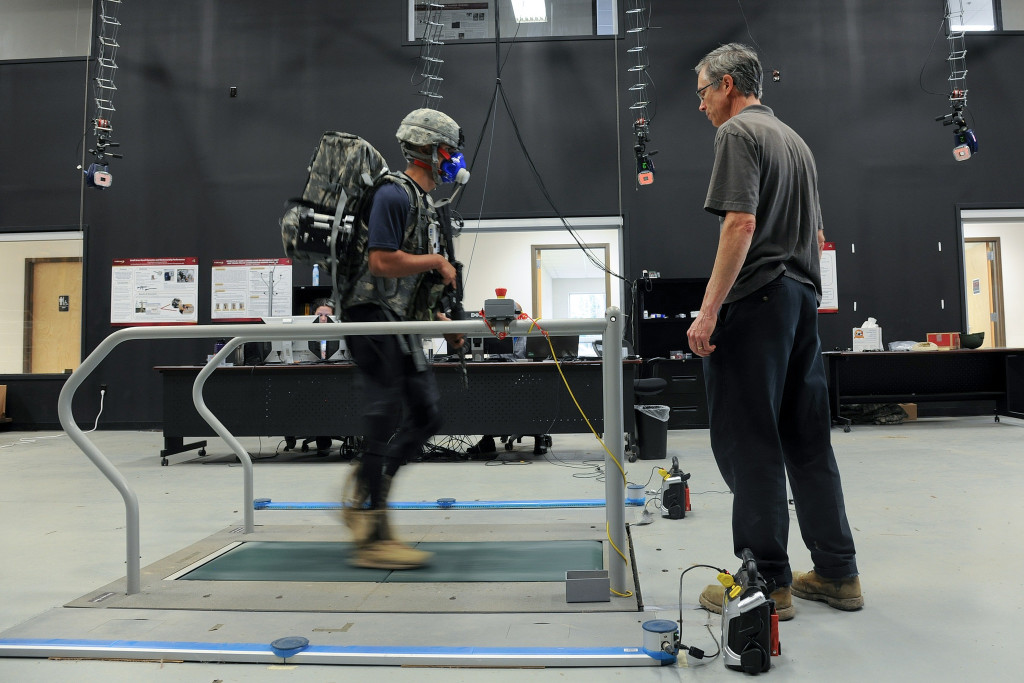

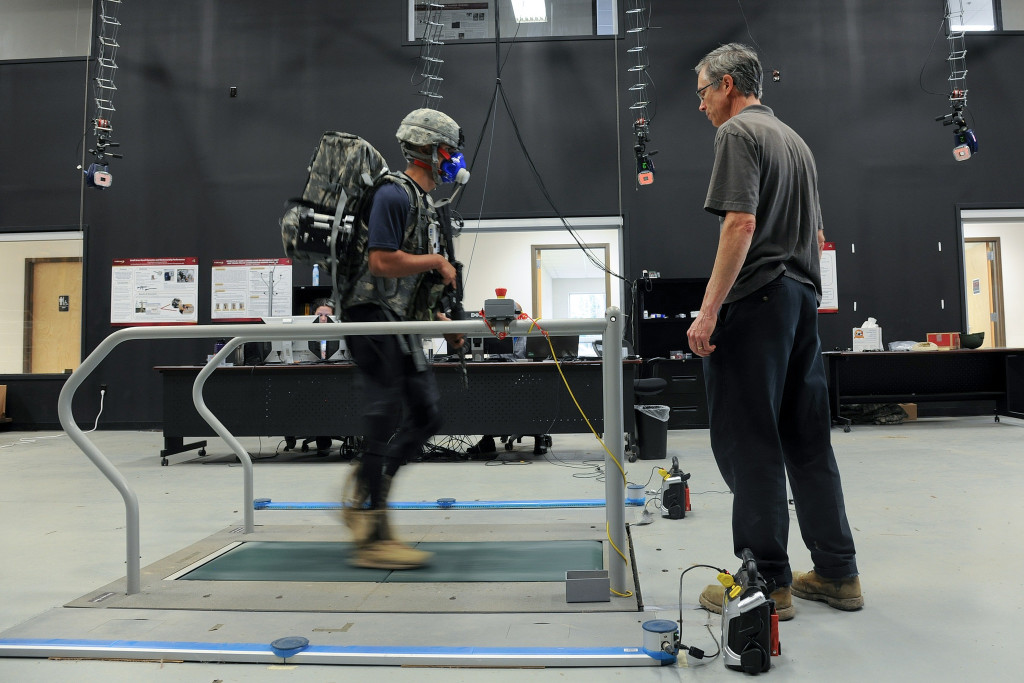

Supporting this focus on draining tasks is a key component of most exosuits: an external frame known as an exoskeleton. Exoskeletons transfer the load a wearer otherwise bears from their own body to the ground, increasing the endurance of the wearer, which among other benefits lowers risks of injury, increases work quality, and can reduce the number of required workers. As demonstrated by Navy shipyard tests of the MANTIS (a Lockheed Martin suit upgraded last year to the FORTIS), exosuits geared towards these types of tasks can use passive, unpowered load-bearing exoskeletons to achieve marked capability enhancements, thereby limiting technological complexity and expense.

But exosuits’ potential value is not limited to mundane tasks. They in fact hold the promise for increased capabilities in other maritime mission areas as well. In part in recognition of the simultaneous development of robotics, whose capability gains in some of the same fields serves as a comparison, we focused on environments in which, and tasks that are aided by, on-scene human situational awareness and judgment, human dexterity and movement, and beyond-human abilities.

This emphasis highlighted damage control, humanitarian assistance/disaster response, and amphibious operation support functions such as those performed by beach master units as ripe for exosuit development. While force protection; visit, board, search, and seizure; and Marine Corps amphibious operations also fall under this rubric, exosuit design for these missions would likely be similar to their ground combat counterparts, requiring such features as armor that could be minimized in the designs we explored.

The cumulative benefit of a range of current technologies and their likely developments over five years will also accrue more to human-enabled exosuits than robots. Advances in low-powered sensors, communications, augmented reality, and embedded medical treatment systems can be integrated for capability enhancements. Human-operated modular attachments can add versatility to mission sets. And in designing powered exosuits for maritime operations, the challenges of supplying that power can be mitigated by tethering to a ship’s supply or through the ready availability of replacement batteries. As Patrick Tucker at DefenseOne notes, a realistic version of the exosuit ground combat in Edge of Tomorrow based on current technology might be closer to “two hours of Tom Cruise hunting for a wall outlet.”

It can be easy to dismiss exosuits as a permanent fixture of fiction. But initial testing suggests that very real capability improvements are attainable now and further gains achievable in the near future. It is time for the Services that operate vessels and sealift, as well as civilian agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to take a serious look at the potential of exosuits in maritime operations.

This in itself involves an investment of time and money, and in the current fiscal environment any proposal for new investment faces strong headwinds. But all budgets are matters of priorities, and the announcement of the Defense Innovation Initiative last November signaled that investing in innovative approaches is a high priority for the Department of Defense. Additionally, some exosuits might even prove cost-savers. As exosuits increase users’ endurance, jobs might require fewer workers or recovery breaks, trained workers can work in the profession longer, and the pool of potential workers can expand to include those not previously physically able – these in turn can lower compensation, overhead, and training costs. Rework costs could be minimized as a result of longer sustained quality. Reduced risk of injury means likely reduced disability payments and lost time. That said, the suits themselves represent an upfront initial cost, require training time, and become more expensive as they move along the spectrum of more advanced, powered suits.

Recommendations

The Navy and seagoing elements of the other services should explore the immediate benefits that low-powered maritime exosuits appear to offer for physically draining tasks like maintenance and begin working out details required for quick adoption, such as storage, training, and required analysis for potential sources of acquisition funding. While powered exosuits appear to offer additional advantages compared to existing approaches for tasks like damage control, delivering a cost-effective powered suit in a reasonable time frame is necessary for the effort to prove worthwhile. This requires a targeted research effort, concrete specifications tailored to the unique and more limited needs of maritime operations, and smart design trade-offs. Further, to guard against creating an unnecessarily technologically complex project, it must be continuously compared with non-exosuit solutions. Exosuits cannot be a $1,000,000 solution to a $10,000 problem, but they look ready to deliver real benefits in maritime operations.

Scott Cheney-Peters is the co-author of CNAS report “Between Iron Man and Aqua Man: Exosuit Opportunities in Maritime Operations.” He is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve, founder and president of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), and a member of the Truman National Security Project’s Defense Council. The views above are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense or Navy.

Photo credit: U.S. Army RDECOM