Why Natural Catastrophes Will Always Be Worse than Cyber Catastrophes

Cyber attacks have been characterized as “borderless” threats. The seeming lack of geographic constraint implies that one skilled hacker, presumably in a hoodie and Guy Fawkes mask, could take down the internet in its entirety. It even happened once, in 1988, with Robert Tappan Morris’ eponymous “Morris Worm.” But that was back when there wasn’t much internet to take down. A lot’s changed since then, but the fear persists — so much that the U.S. government is even contemplating a backstop mechanism for the economic effects of truly catastrophic cyber attacks. That might be a bit hasty, though. Despite the fact that cyber attacks are said to be on the rise, they’ve fallen short of the “mass effect, including casualties and destruction” described by James Lewis as a necessary feature of catastrophes. His claim that there hasn’t been a cyber catastrophe in 25 years is debatable because his definition is so strict, but its spirit is unimpeachable. Lewis’ high-level comparison of the damage from cyber events to those of natural catastrophes got my attention — in part because it’s correct and in part because nobody has taken a slightly deeper dive into the data. Having developed platforms and led teams focused on estimating the economic and insured loss consequences of both natural catastrophes and cyber attacks at the data and analytics firm Verisk, I’ve seen the differences in economic destructive power between them.

Although natural catastrophes are believed to be limited in their potential economic impact because they are confined by geography, the characteristics of such events make them much more impactful economically than their cyber counterparts. The reversibility of cyber attacks is an important part of the reason why. Damage from natural catastrophes is far more difficult to unwind. This article reflects some of my findings from recent research on how to better understand the economic damage from recent cyber catastrophes and what the size of those losses relative to the economic losses from natural disasters suggests about economic security threats via the cyber domain in general. The findings can inform discussions about a federal backstop for cyber catastrophes. Given that the effects of natural disasters have been so much more severe and pronounced than those from cyber, it is clear that the economic losses from cyber events should be relatively absorbable.

By the Numbers

One of the reasons why cyber catastrophes and their economic effects are so often misunderstood is that the sector lacks a reliable scorekeeper. There’s no easy place to go to find out how much cyber catastrophes have cost over the years, which were the most expensive, and whether there have been pockets of unexpectedly high loss activity. For natural disasters, the situation is much different. We understand the effects of hurricanes and earthquakes, for example, because we have plenty of data from reliable. Munich Re NatCatSERVICE and Swiss Re sigma are robust databases covering both economic and insured losses for natural catastrophe events and offer half a century of history. The databases come from the two largest reinsurance companies in the world. They are not just resources for the insurance community, but also for broader research purposes, and they are well respected in both commercial and academic communities.

Munich Re NatCatSERVICE collects data from a wide range sources — to include “government agencies, scientific institutes, associations, the insurance industry, the media, and other publicly available sources” — and uses it to develop estimates of insurance industry and economic losses from natural disasters using the company’s in-house data and expertise. The methodology used by Swiss Re for sigma is largely similar, with economic loss estimates culled from publicly available sources, although some estimates are calculated using data the company collects through the normal course of its reinsurance business. The data from these sources has been accepted widely for both academic and research use, not to mention robust adoption by other stakeholders. For cyber events, it’s not so easy. There is no equivalent to Munich Re NatCatSERVICE or Swiss Re sigma. Overall, there has been little to consult for past events, which has fueled the belief that there is little in the past to consider.

I first started looking into the economic losses associated with cyber catastrophes in 2019, when I published an informal collection of historical losses, and I updated that list in an article published four years later on the principle of reversibilityin cyber attacks. For both pieces, the data set was incidental to their core purposes — a helpful resource, but not the result of a disciplined, rigorous research effort.

Since then, my conversations in policy, security, and insurance circles have increasingly made clear the need for a historical data set on the economic losses from cyber catastrophes. Not only would the reference point be useful, but it would also address the belief that there’s no relevant precedent for cyber catastrophes. The past exercises offer a decent starting point for formal and more rigorous data collection and analysis. The process I developed and implemented isn’t all that different from those used by Munich Re and Swiss Re, relying on publicly available data qualitative analysis of economic loss estimates to determine the best estimate for each historical event.

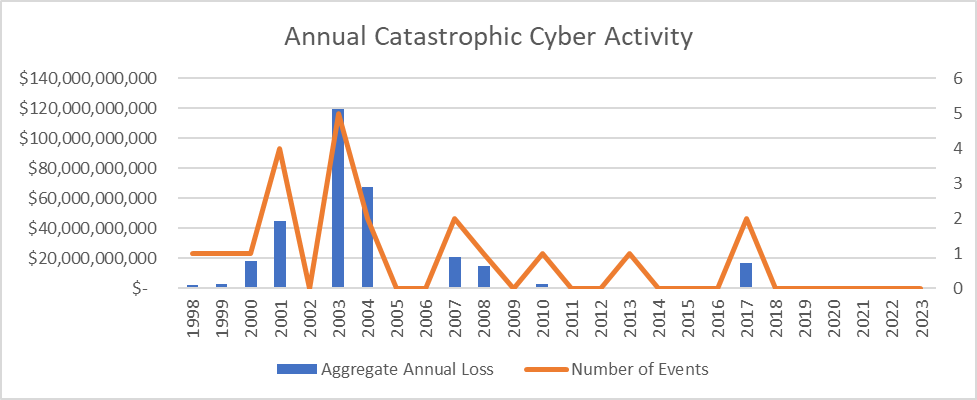

I found 21 cyber catastrophe events since 1998 with attendant economic losses adding up to a total of $310.4 billion. The reporting standard I’ve employed isn’t as severe as Lewis’ in that it doesn’t require mass injury or physical damage. It does, however, require mass impact. An attack on a single company, like Equifax, isn’t a catastrophe, even if the economic loss is comfortably above the threshold. In Property Claim Services (PCS) parlance, an event would have to affect a “significant number” of companies. Finally, the economic threshold for an event to qualify is $800 million, adjusted to 2023 for inflation at 3 percent per year.

Absent any context, these big numbers may seem meaningful. The total of $310 billion breaks down to $12.4 billion per year, with 2003 alone showing nearly $120 billion in aggregate economic loss from cyber catastrophes. At the time, some even felt the high estimates being publicized were unnecessarily alarmist. Interestingly, they likely were neither alarmist nor exaggerated. When compared to the economic impacts of natural disasters during the same period, the economic effects of cyber catastrophes don’t seem terribly catastrophic.

From 1998 to 2021, the last year for which data is available on the platform, sigma puts aggregate economic losses from natural disasters at approximately $4.3 trillion. That’s nearly 14 times the size of aggregate cyber catastrophe economic losses during the same period. The total cyber catastrophe loss is roughly the size of the economic loss from the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011. The economic losses from natural disasters in 2005, which included Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma, reached $326.1 billion. The difference in scale makes natural disasters and cyber catastrophes almost literally incomparable.

This probably feels counterintuitive. Cyber attacks are borderless, right? WannaCry is believed to have infected computers in around 150 countries, yet it only caused economic losses of $4 billion. Meanwhile, Hurricane Ian was largely limited to Florida and the Carolinas, and it led to economic losses of around $100 billion. If it feels like something isn’t adding up, it’s because we’ve been looking at these two threats the wrong way. What matters most is reversibility — i.e., how easy it is to undo the damage from an event.

Damage Undone

When it comes to disaster, reach is far less important than physical impact. Lewis noted that mass physical damage from cyber events hasn’t been realized, and the contrary is observably true for natural disasters. Reversibility is an important and often overlooked aspect of physical impact, as it defines the longevity of damage. Small-arms damage, for example, is generally reversible, while nuclear attacks are not. Cyber attacks have been demonstrably reversible, given their transitory nature. U.S. institutions and communities have become quite adept at reversing the damage from natural disasters, but their widespread physical impact makes the process much slower and labor-intensive than remediation after cyber attacks. A comparison of two events makes this clear.

In 2015, a cyber attack on the power grid affected 230,000 people in Ukraine. Due to what has often been characterized as an act of cyber war (a questionable use of that expression at best), the lights were out for as long as six hours. This came as part of a wave of cyber attacks on the grid in 2015 and 2016, none of which had any further meaningful impact. The 2015 cyber attack-induced blackout tends to be seen as the “success story” for offensive cyber against power grids, even despite the lack of sustained impact. Natural catastrophes, on the other hand, have had no trouble depriving millions of people of access to electricity for days at a time. One of the most interesting cases for closer study, though, is Hurricane Ida.

Hurricane Ida challenges the belief that natural catastrophes, due to geographical constraint, are limited in their potential impacts. First, the storm was hardly limited by geography. It made landfall in Louisiana and ultimately affected more than a dozen states directly or indirectly before leaving the northeastern United States in its wake. The overall economic loss from the storm exceeded $65 billion, according to Munich Re NatCatSERVICE. Yet, you don’t need to view the storm as a whole to understand the challenges associated with reversibility.

Let’s go back to Louisiana, where 1.1 million people went without power for more than a week. Compared to the 2015 cyber attack in Ukraine, the depth and breadth of the outage is incredible. However, the week-long outage should be seen as brief, given the effort required to bring the lights back. Hurricane Ida “destroyed more than 22,000 power poles, 26,000 spans of wire and 5,261 transformers — that’s more poles damaged or destroyed than hurricanes Katrina, Zeta and Delta combined.” Cyber catastrophes could thus be seen as more geographically constrained than natural catastrophes, when viewed from the perspective of remediation efforts. The need to engage directly with what has been damaged is far more concentrated. The relative speed and ease with which cyber catastrophe damage can be reversed appears to have created an upper limit for economic effect, while the need to go out and fix broken equipment after a natural disaster necessarily takes more time, people, and expense.

Neither a Cyber Andrew nor a Cyber 9/11

Past results don’t matter, of course, when the “Big One” is right around the corner. Yet, such an event would have to be of seeming unimaginable magnitude, given not just the size of past losses but the fact that their economic effects have largely been forgotten. In the insurance industry, the ghost of Hurricane Andrew is often summoned. The society-changing cyber attack that many fear is often referred to as “Hurricane Andrew of cyber.” Hurricane Andrew was massive. If it happened today, the storm would cost the insurance industry approximately $100 billion, suggesting the economic loss would likely approach $300 billion. The event resulted in 11 insurer insolvencies and cost 44 people their lives.

More relevant to cyber catastrophe risk, Hurricane Andrew changed behavior. If it were to happen today, the financial impacts — to the insurance industry and society as a whole — would be more easily absorbed through increased risk management sophistication and deeper pools of capital. Hurricane Andrew also led to the mainstreaming of catastrophe models. The terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 had a similar effect. They changed how insurers and reinsurers view and analyze political violence risk and led to increased actuarial and modeling rigor. The most prominent development, though, was the development of a terror insurance backstop.

The Terrorist Risk Insurance Act provided support for an insurance industry reeling from a profoundly expensive loss event and filled an important economic security gap for society. Perhaps the best indicator of the success of the backstop is that insurance is widely available, suggesting that the backstop served its purpose by giving the industry breathing room to come back into the sector. The notion of a similar solution for the cyber insurance sector has been raised, but the situation is much different from the cases of Hurricane Andrew and the Sept. 11 terror attacks.

First, there has been no transformative cyber attack. If scale alone were sufficient, then one could argue the Andrew of cyber likely came in 2003 or 2004, whether as a single event or pocket of peak activity. Beyond scale, interest in improved cyber catastrophe models has come mostly from potential capital providers, not from a necessary sea change in threat or loss activity. There hasn’t been a loss large enough yet to rethink the risk. And it seems that such a loss is itself unlikely.

Speculation has filled the gap left by experience, with fantastical cyber catastrophe scenarios offered for contemplation. One recent example is the prospect of a $3.5 trillion scenario recently published by insurance marketplace Lloyd’s of London. Even with that economic impact spread across five years, the case strains credulity. It would require a single event more than 10 times larger than all cyber catastrophes of the past 25 years and more than 80 percent of the cost of 23 years of natural disaster losses. To hedge for such an unrealistic possibility is to divert resources and focus from where they could be more productive.

A Dose of Reality

Cyber catastrophe risk tends to be treated as bigger than it is, the natural consequence of uncertainty over past experience. Improvements to scorekeeping show that the economic effects of cyber catastrophes are utterly manageable. Given how small they have been relative to natural disasters — the effects of which have been managed well — there is clearly precedent. The potential effects of cyber catastrophes that have been left either to guesswork or to extrapolation from thin sources ought to give way to a deeper understanding that more fully contemplates the rich history of cyber catastrophe economic loss data that has largely been ignored. While there may be a role for backstops and other means of support for economic security in the face of major cyber threats, such measures should reflect the realities of the risk.

The direct comparison to natural disasters goes a step further. We understand hurricanes and earthquakes — and lately wildfires and winter storms — as major economic events. There have been plenty of them for decades, and they have decent economic loss estimates assigned to them that have been largely accepted for as long as they’ve been published. The development of historical cyber loss estimates not only provides a reference point for cyber itself, but also allows for the natural comparison of two kinds of catastrophe. We’re starting to get to know cyber catastrophes the way we know natural disasters. It’ll take more time, but we should stop lamenting the perceived lack of data and experience and start putting what we now have to work. We may still be in the dark, but light is starting to shine through the cracks. Lewis identified an interesting and important point of comparison for cyber catastrophe, and the discussion above remains superficial compared to what is possible with further research. With more eyes on the problem, our understanding of cyber catastrophes as an economic security problem will only improve.

Tom Johansmeyer is a POLIR Ph.D. candidate at the University of Kent, Canterbury. Based in Bermuda, where he also works in the reinsurance industry, he was previously the head of Property Claim Services (PCS) at data/analytics firm Verisk, which provides data on industry-wide insured loss events for both natural and man-made disaster events. In this role, he developed the first such tools for global cyber risk. Tom proudly pushed paper in the U.S. Army in the late 1990s, and if you were in the 2nd Infantry Division in 1998, you might have bugged him for your reassignment orders.

Image: Master Sgt. Michel Sauret