Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

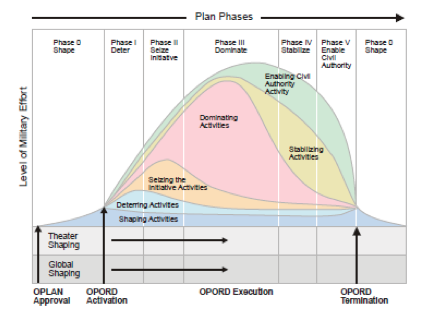

The diagram below, drawn from U.S. Joint planning doctrine (JP 5-0), graphically depicts America’s current model for designing military campaigns, its way of battle. The diagram first appeared in U.S. doctrinal publications in the early 2000s, but it was under development during the 1990s. It represents an ideal campaign or battle; and one can detect traces of Desert Shield and Desert Storm in the way the division and sequence of activities are portrayed. It is risky to take any ideal as a model for reality, particularly a misleading one. Yet, for more than a decade that is exactly what we have done.

This planning construct was developed during an era in which the U.S. military reduced its force structure by more than a third, and withdrew its presence overseas substantially. As one might expect, the model reflects the prevailing assumptions of that period. It assumes, for instance, the U.S. military would deploy as part of a “crisis response” force into an uncertain and complex strategic or operational environment, and would likely have to do so with little or no warning. Many analysts make similar assumptions today. However, the model also supposes the intensity of military effort would peak in Phase III with the neutralization of the adversary’s combat power (hence, a way of battle). The model further assumes the United States would have little need (or desire) to retain troops in the crisis area for an extended period of time in order to maintain dominance and establish stability. The latter two assumptions were dashed to pieces by the recent campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

American strategists and doctrine writers are now working to revise this planning construct. Their main goal is to ensure what we currently refer to as Phases IV and V are better represented in a manner that reflects their obvious importance. We should support their efforts in any way possible.

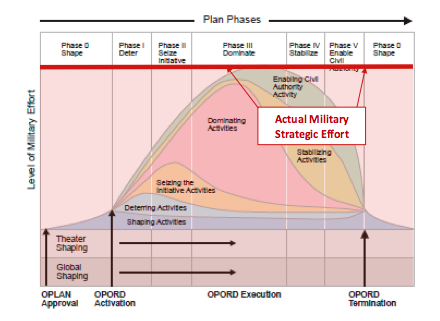

At the same time, if the left half of the diagram remains unchanged, the revision will have fallen short. With Iraq and Afghanistan in their minds, pundits often claim wars are won in Phases IV and V, but that is not necessarily the case. Wars are usually won in what the model depicts as Phases 0 through II; that is, they are often won before the first shots are fired and well before decisive operations and stabilization efforts. When conflicts must be won in Phases IV and V, military strategists have neglected a critical part of their task: conduct a sound net assessment. This failure typically stems from faulty assumptions, which in turn lead to their closely related kin, inadequate preparations. The intensity of the military strategist’s effort should thus peak well before major combat operations, if it peaks at all.

History’s great strategic thinkers — Sun Tzu, Clausewitz, Jomini, and others — have said as much. To be sure, each defined strategy and war differently, based on their experiences and the influences of their times. Yet, when we strip away the rhetorical flourishes and the barriers erected by historical distance — and when we read not just select chapters of canonical works on strategy, but the treatises themselves holistically — we find more than nominal agreement. One major point of consensus concerns the importance of strategic thinking and analysis done well forward of the first clash of arms.

For instance, readers might recall Sun Tzu’s adage that subduing the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill. The broader meaning of this saying is to neutralize threats before they arise or, short of that, acquire so many advantages (politically, economically, culturally, informationally, and of course militarily) before hostilities commence that the fighting itself is merely a follow through. That, in a nutshell, is the core task of the strategist. Naturally, even such advantages can never guarantee victory. They can, however, increase its odds tremendously or, at the very least, they can put us in a better position for a negotiated settlement.

Thus, our conception of “military effort” should include more than kinetic force. It should refer to the sum of all activities, military and otherwise, necessary to out-position our foes in ways that facilitate getting what we want. Accordingly, our military effort should always be at least as high before major operations as during them. Even so, as Clausewitz reminds us, a strategist’s work is never done. Our strategic activities must remain continuousthroughout the conflict, leveraging victories and defeats, consciously and actively, for the purpose of the war. Hence, the level of military effort, as more than kinetic force, must be adjusted, as depicted in this next diagram.

In sum, America’s way of battle errs not only because it attempts to realize an ideal (which by definition cannot exist), but also because it strives to achieve the wrong ideal. Our model for military planning should not be based on heady abstractions or wishful thinking, but on inductive analyses covering a wide variety of campaigns and operations. The goal of such research ought not to be another catchword, but rather greater understanding of how armed conflicts tend to unfold, which is ultimately more valuable. The data for such analyses already exist. Analyzing them might take time, but the effort is clearly worthwhile and in the long run “cheap at twice the cost.”

Our new model for designing campaigns must bring our strategic thinking and our campaign planning closer together. That in turn might make it possible to move from an overwrought way of battle toward a genuine way of war.

Dr Antulio J. Echevarria II is currently the editor of the US Army War College Quarterly, Parameters. He is a former US Army officer and author of four books, to include most recently Reconsidering the American Way of War: From the Revolution to Afghanistan (Georgetown 2014).

Photo credit: U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. James J. Vooris