(W)Archives: A Civil War Surgeon’s Thoughts on the Eve of a Bloody Battle

On this date in 1862 the Second Battle of Bull Run started. It lasted until August 30. The clash was the culmination of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s effort to bring the Union’s Army of Virginia under Gen. John Pope to battle before it could be reinforced by the Gen. George McLellan’s Army of the Potomac. McLellan’s troops were at that time evacuating the Virginia Peninsula and heading back north by sea, having been bamboozled and defeated in the Peninsula Campaign. The battle was a tactical victory for the Confederates and, as a contemporary sketch in the Library of Congress shows, Pope’s army was forced to retreat. Two weeks later Pope was relieved and his army was absorbed into the Army of the Potomac. The Confederates’ string of victories continued.

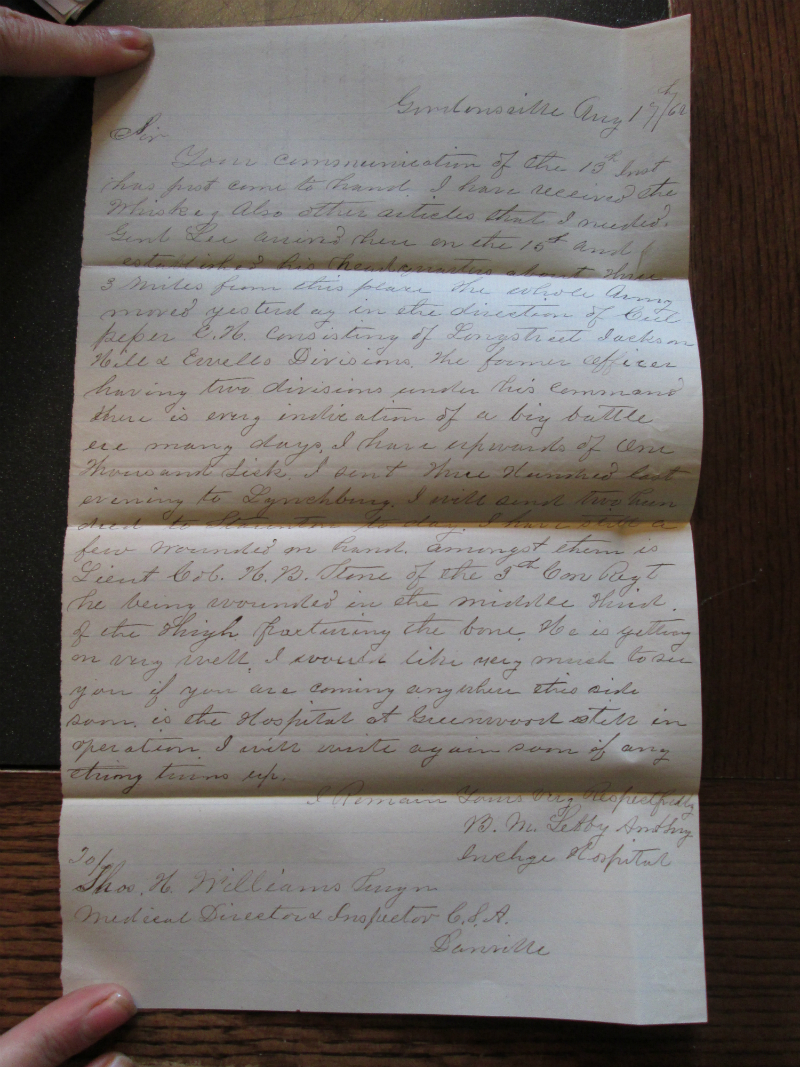

One low-level Confederate saw the battle coming. On August 17, 1862, a Confederate Army surgeon whose name appears to be Lefby Anthony wrote to Thomas H. Williams, the Confederate Army’s Medical Director and Inspector of Hospitals in Virginia. The neatly written, brief letter, held at the U.S. National Archives in Washington, DC, reported that Anthony was in Gordonsville, Virginia, had “received the whiskey,” and had “upwards of one thousand sick,” even after having dispatched 300 to Lynchburg the day before. By contrast, he had only a few wounded on hand. In addition, the letter noted almost matter-of-factly that Lee had arrived and set up his headquarters in Gordonsville on August 15, and that the whole army — including Gens. James Longstreet, Stonewall Jackson, A.P. Hill and Richard Ewell — had moved toward Culpeper on August 16. “There is,” Anthony wrote, “every indication of a big battle ere many days.”

Anthony was right. Though a sketch drawn from a safe distance makes the Second Battle of Bull Run look like a grand affair, the butcher’s bill was high. Union casualties were some 10,000 and the Confederates lost approximately 1,300 Confederate dead. In addition, there were 7,000 Confederate wounded for Anthony and his colleagues to look after. Lee, meanwhile, used this bloody victory as a springboard for an advance across the Potomac, into Maryland, and toward an even bloodier battle, the Battle of Antietam, after which McClellan would be relieved.

The Civil War ended slavery and restored the Union. But it can be more difficult to find any silver lining in the cases individual, bloody battles. If there is one to be found in the carnage of Second Bull Run and Antietam, however, it is alluded to in the figures laid out in this surgeon’s letter. Before the war, doctors suffered from a shortage of cadavers to study. The war solved that problem. Because the Confederacy had such a small population, its surgeons focused their efforts on getting the sick and wounded fit for a return to duty. By contrast, the Union army also used the opportunity to gather data about the dead, wounded, and sick. New scholarship suggests that research based on that data allowed the post-war reform of American medicine, setting the stage for a modern, more scientific understanding of medicine. Not only does war make states, but out of bloodbaths like Second Bull Run and Antietam can come useful knowledge, the effects of which can be seen well beyond the battlefield.

Mark Stout is a Senior Editor at War on the Rocks. He is the Director of the MA Program in Global Security Studies and the Graduate Certificate Program in Intelligence at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Arts and Sciences in Washington, D.C.