The Great National Destiny: Lessons from Andrew Jackson’s Navy

In January, retired officers debated the future of the aircraft carrier. In May, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus proposed reforms to the personnel system. And in June, the Navy considered the growing presence of a peer competitor in the South China Sea. These and other discussions on the utility of the Navy and how to advance amidst the challenges of the early twenty-first century are not new. The Navy might be reminded of another period from which to draw lessons for this new era. The past is often prologue.

When he assumed the office of the President of the United States in March 1829, Andrew Jackson was known primarily as the hero of the Battle of New Orleans and as a general during the First Seminole War. He had just defeated John Quincy Adams — whose father, as president, created the Navy — in one of the most contentious campaigns in American history. His best known twentieth century biographer argued that Jackson had no interest in the Navy and understood it even less. The reality, however, was different. Jackson’s presidency ensured the right force mix for global operations, instituted personnel reforms, improved the Navy’s finances, and advanced new technology. These factors have been vital to naval operations since that period.

The Influencers

It was easy for Americans — many of whom served in local militias — to understand the need for an army. The results of its work in pushing the country westward were tangible and visible and reportable in the media. However, the maritime environment was less defined, and the Navy was less understood because it often fought largely over the horizon. The War of 1812 was quickly becoming a distant memory and irregular wars such as suppressing piracy in the West Indies in the 1820s received far less coverage. The Navy needed to make the American public understand its global imperative. It needed apostles. It needed a champion. It found the latter in the most unlikely of characters — a former Army general. Although naval historians argue that turn-of-the-century navalists such as Theodore Roosevelt, Alfred Thayer Mahan, Henry Cabot Lodge and others instituted an American mindset envisioning a great maritime power, its genesis really came in the 1830s.

Jackson’s first inaugural address was minimalist in discussing the Navy. He called for a “gradual increase of our Navy” and of “progressive improvements in the discipline and science” of both branches. Because he perceived existing financial mismanagement in the department, Jackson immediately set out with appointing his loyalist, Amos Kendall, as Fourth Auditor of the Treasury, responsible for all Navy accounts. Jackson’s revisions, under proper regulations of the period, of Navy courts-martial set a new standard for officer accountability in the nineteenth century. Any doubt regarding Jackson’s views of the Navy are dispelled by his lengthy assessment of the valued branch in his farewell address in March 1837. The Navy was, he argued, the guarantor of commerce, the force upon which “our respected flag” was proven throughout the world, the country’s “natural means of defense” as well as the “cheapest and most effectual.” It would, he wrote, “not only protect [the nation’s] rich and flourishing commerce in distant seas, but will enable [the country] to reach and annoy the enemy … meeting danger at a distance from home.” Jackson knew what every leader of the nation should: “we shall more certainly preserve the peace when it is well understood that we are prepared for war.”

The second important group of influencers were junior naval officers who launched an insurgency against the senior officers of the 1830s. This new generation of officers was the first to serve largely in peacetime. This enabled them to study other civilizations and cultures, to learn about the world around them, and the role of the Navy in the coming century. They established the Naval Lyceum, the predecessor of the U.S. Naval Institute. The Lyceum was part museum, part library, part lecture hall, and part facilitator of communications between the officers. It established the first periodical devoted to naval issues, The Naval Magazine, which became the source of new ideas, discussing the implementation of steam technology, pushing such issues as a South Seas Exploring Expedition, changing rank structures, professionalizing the officer corps, and advocating a new naval school.

The third group of influencers were the literary giants of the early republic. They were men with ties to the Navy, either having served in it earlier in their careers or with relatives who had served. Some, like James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving, were members of the Naval Lyceum. Others were newspaper editors such as Jeremiah Reynolds. It was the decade that produced Richard Henry Dana, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and James Kirke Paulding, who became secretary of the navy under Martin van Buren. These literary figures were able to move the issues and the romance of the sea and the Navy beyond the confines and echo chamber of the Department of the Navy. They engaged the American public by conveying ideas through naval-oriented fiction such as Joseph C. Hart’s 1834 Miriam Coffin, in which he wrote that the country was “informed by a strident maritime nationalism. Supremacy on the ocean is America’s great national destiny.”

If there is any indication that the American public was receptive and supportive — or at least pre-disposed — it could be found in the observations of a foreign traveler during that decade. “America,” Alexis de Toqueville wrote in his seminal Democracy in America, “was born to rule the seas as ancient Rome was destined to conquer the ancient world.” If the country was born to rule the seas, Jackson ensured its navy began to reflect that imperative by ensuring the fleet was appropriately structured and officers enabled to lead the Navy on distant stations.

Jackson’s Navalism

Right Force Structure. Presence is impossible without platforms. The greater the presence required, the more platforms are needed. At the end of the War of 1812, the United States began building 74 gun ships-of-the-line to compete with the Royal Navy. However, they were completed too late for combat and were used sparingly as flagships on distant stations. The only ship-of-the-line constructed during Jackson’s administration was the 140-gun behemoth USS Pennsylvania. As Congressman Joel Sutherland argued, “It ought to be fitted out and launched and sent to foreign ports, that it might there be seen what American naval architecture was, what the seamen were, and what force we could command in war.” The Committee on Naval Affairs, however, was opposed to it, preferring instead ships of 16 to 20 guns (the schooners and sloops.) Although finally constructed in 1837, the USS Pennsylvania never left U.S. territorial waters.

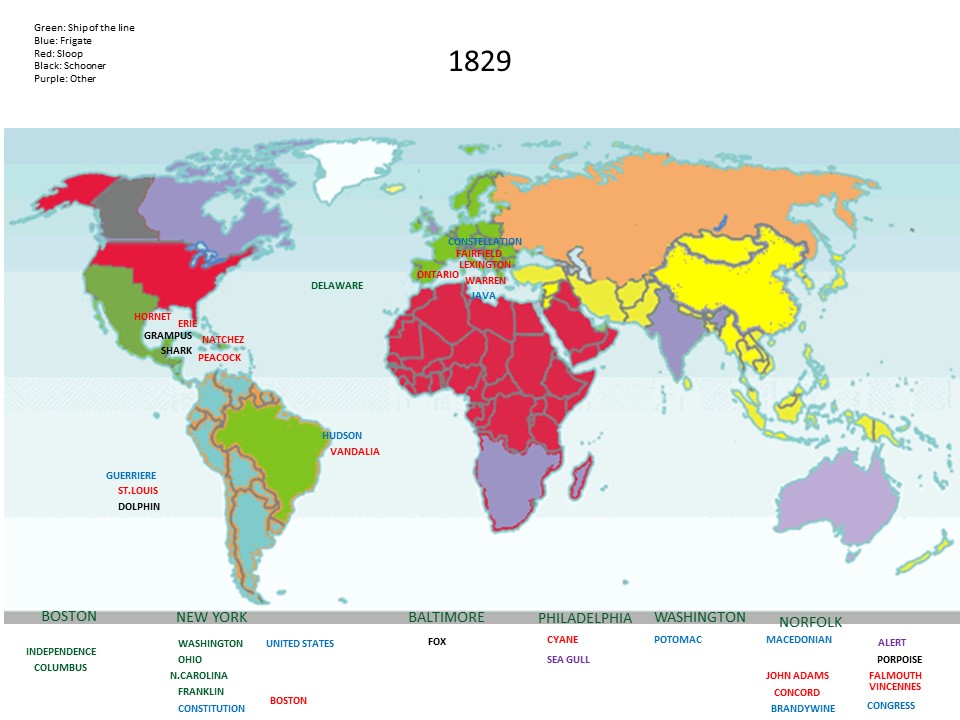

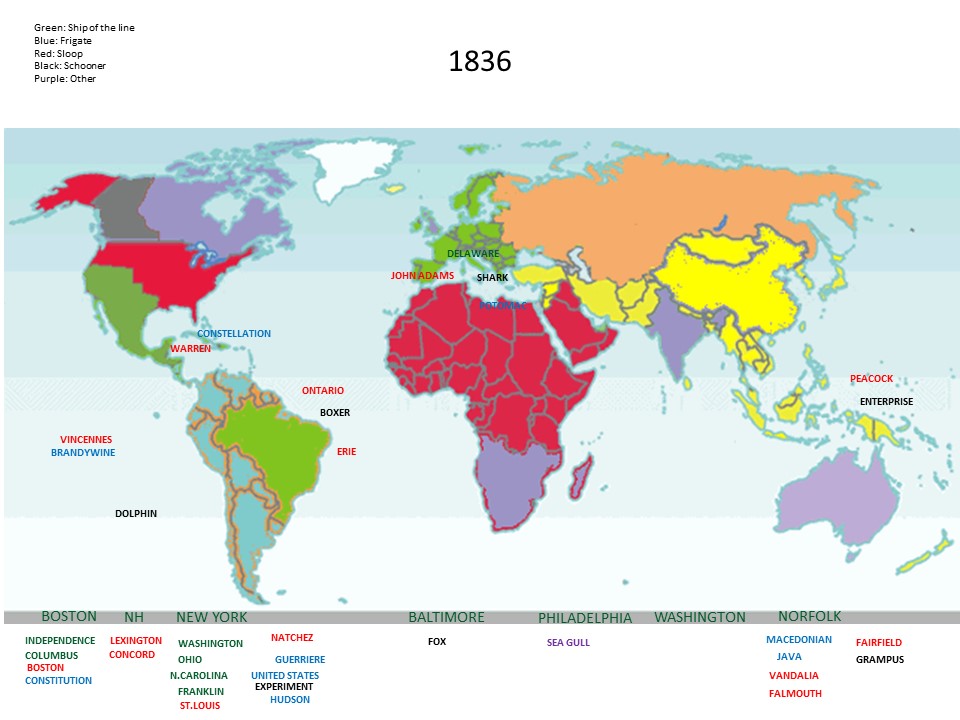

The real work-horses of the Navy in the antebellum period were not the ships-of-the-line nor even the frigates. They were, instead, the trusted sloops and schooners. The Jackson administration understood the cost of maintaining big ships overseas, preferring the small, agile, and more numerous sloops and schooners, though frigates continued to be used in punitive raids. Sloops and schooners were available to interdict illicit slave traders off West Africa, protect the U.S. whaling fleet in the eastern Pacific, conduct patrols off Brazil, and even for survey and exploration at the end of the decade with the South Seas Exploring Expedition. Sloops and schooners were also ideally suited for the anti-piracy missions of the West Indies Squadron because the shallow waters of the Caribbean demanded shallow drafts.

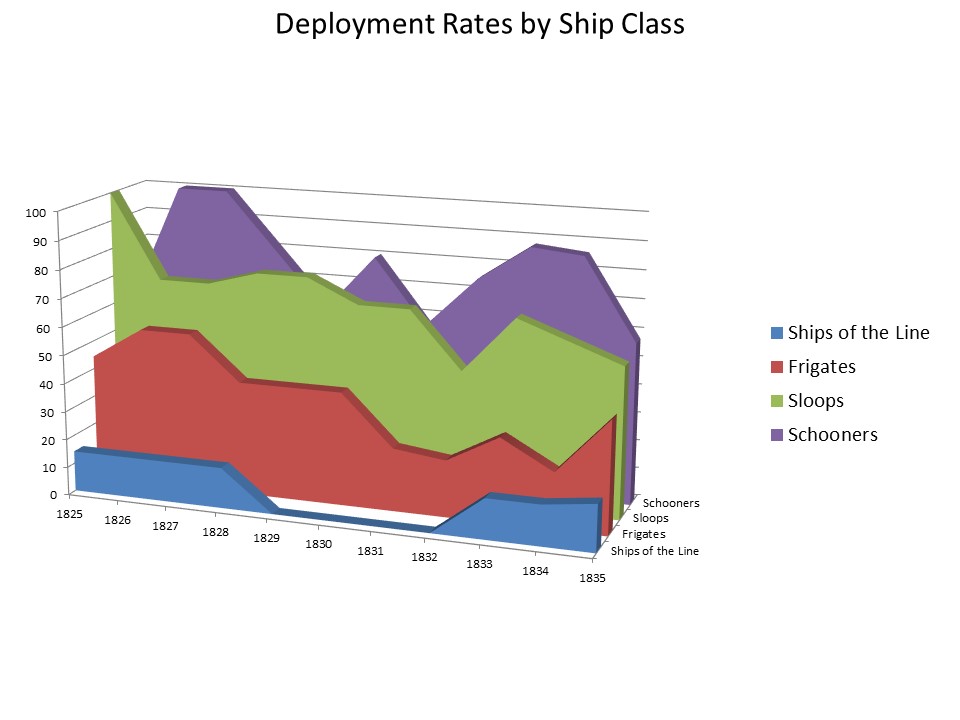

Throughout most of Jackson’s presidency, only one ship-of-the-line out of seven deployed, namely the USS Delaware as the flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron. Only between twenty to forty percent of all frigates were deployed annually. Sloops and schooners on the other hand, had deployment rates of eighty percent or more (see graph). Although sloops and schooners were sufficient for this sort of operation, the Jackson administration understood that there was still a need for larger ships. For example, it sent the USS Potomac to respond to an attack on a merchant ship in Quallah Battoo, Sumatra. They would also be useful in a war with a great power. Frigates and ships-of-the-line already in the yards could be quickly completed generally within three months as many of the materials had already been purchased.

In the end, Jackson’s Navy remained a balanced force whose presence was made able by the number of sloops and schooners as well as the justifiably cautious introduction of steam-driven ships without reducing the fleet size. When it came to naval technology, Andrew Jackson was no Luddite. He was already familiar with the advantages of steam technology on the water. The U.S. Navy had, with Robert Fulton’s Demologos, built the first steamship of war, prior to Jackson’s administration. But Jackson facilitated the travels and introductions in France and England for John Lenthall, apprentice to naval constructor Samuel Humpheys, to learn how Europe was building their steamships of war. Although the Board of Naval Commissioners, comprised of the older, conservative officers, opposed steam technology as new and untried, the Jacksonians pursued it as part of the future Navy. Commodore James Barron proposed a tri-hulled, steam-powered paddle-wheeled ram ship. While that was, in the end, unfunded, Jackson did order two steamships to Florida to support army operations and riverine warfare at the outset of the Second Seminole War.

Evolutionary, Not Revolutionary. As his inaugural address suggested, Jackson undertook, “progressive improvements” in the Navy, tempered by the realities and limitations of the new industrial era. Despite his attempt to combine the Army and Marine Corps — a situation that was rectified by An Act for the Better Organization of the Marine Corps in 1834, securing it within the Department of the Navy — he did not attempt wholesale changes based on sweeping unrealistic expectations.

Personnel reform was an important issue of the day. The movement began with criticism of the number of captains — then the highest naval rank. Of the 37 captains serving in 1828, all had served during the Barbary War and none were required to retire, thwarting advancement of junior officers. Senior officers advocated creating the rank of admiral but there were already more captains than there were ships in the navy. Although it would take nearly two more decades to address retirements, the conversation began during the 1830s.

Nevertheless, some incremental improvements were made with regard to professionalizing the military. For instance, despite the fact that chaplains had served on U.S. Navy ships since the Revolutionary War, a formalized Chaplain Corps did not appear until the Jacksonian Era. Similarly, in 1830, a Jacksonian Congress proposed a Surgeon General of the Navy that led to a medical corps by the end of the decade.

Naval education also experienced positive, incremental changes. In some cases, the Navy and the private sector attempted innovative and collaborative measures. For example, in 1830 the new Columbia College president William Duer offered to Commodore Isaac Chauncey schooling for the local young officers. Chauncey was cautiously intrigued by the offer and wrote to Secretary of the Navy John Branch: “This proposal is a liberal one, not more expensive than the navy yard schools … I certainly should prefer a Naval School, if Congress would authorize one.”

It was, however, the naval school for officers that captured the imagination of the junior officers as an absolute necessity to properly teach science since schools at sea were not conducive to learning. A naval academy could also serve to vet applicants and candidates. “The first examination for admission,” wrote one author “would reject many applicants, and the subsequent years of probation would winnow away all the chaff, all the incorrigibly stupid, all the vicious, all the insubordinate.” Alexander Slidell Mackenzie also suggested a “school ship” for midshipmen. Ironically just five years later Mackenzie commanded USS Somers, the only ship in U.S. history to have had a confirmed mutiny; his actions in responding to the mutiny directly contributed to the creation of the permanent Naval Academy in 1845.

Forward Deployment. The geo-political situation under Jackson’s presidency was little different than the early 21st century. It was a period of global instability and regional challenges. South America had been roiling in revolutions and civil wars for more than a decade when Jackson took office. The Caribbean, in the post-piracy environment, remained comparatively calm but the Gulf of Mexico was problematic, with a newly independent state of Texas and the potential for a Spanish invasion of Mexico. Even Europe, the center of empires, experienced uncertainty with the Revolutions of 1830 in France and the First Carlist War in Spain. A study of individual ship deployments from ship logs and annual reports from the secretary of the navy indicate that during Jackson’s administration, there was a fleet concentration in the Caribbean, but no dynamic “pivot.” Instead, with a fleet of only three dozen ships, Jackson ordered ships and squadrons where they were needed in response to crises, or in order to prevent them, in a more distributed fashion. By the end of his administration, he also created the East India Squadron to protect U.S. commercial interests in China and the broader region.

Conclusion

Every era has its unique challenges. Jackson’s presidency was no different. He needed to clearly set an agenda for the Navy but in so doing had to have an inherent understanding about its constitutional, strategic, and operational role in the world, particularly as the country was on the cusp of unprecedented growth. Although the Navy experienced setbacks in the 19th century, Jackson and his supporters provided a secure baseline for the service’s global presence, adaptability, and professionalization. By identifying strategic interests, Jackson easily shifted assets to respond to growing areas of instability. This was why, by the end of his administration, he had gained a true appreciation for the role of the Navy and its various missions.

Claude Berube is a contributor to War on the Rocks. He is the co-author of three non-fiction books, more than fifty articles, and author of the Connor Stark novels published by Naval Institute Press. He teaches at the U.S. Naval Academy. Follow him on Twitter: @cgberube.