What Napoleon Can Teach Us About the South China Sea

In trying to understand America’s “great power competition” with China, observers have offered a range of historical analogies. Graham Allison invoked the “Thucydides Trap,” referring to Athens and its war with Sparta, while a recent compilation asked, in reference to World War I, if a U.S.-Chinese clash could be the next great war. But perhaps the Napoleonic Wars offer a better analogy.

Britain ultimately defeated Napoleon because it maintained its alliances better than France. During the long conflict from the 1789 French Revolution to the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, Britain understood that alliances were central to maintaining economic strength, naval dominance, and a favorable balance of power on the continent. These are lessons that would serve the United States well in the South Pacific today. Ideally, by studying this history, the United States could do one better than Britain and avoid the need for a decades-long world war entirely.

Britain Tested

In their 18th century geopolitical competition with pre-revolutionary France, British leaders focused on two strategic pillars: preserving naval superiority on the seas and a balance of power on the European continent. Naval superiority was crucial for the British economy since it secured Britain’s colonies and its lucrative global trade network. A balance of power on the continent was crucial to ensure that one power did not emerge to dominate Europe. Since Britain could not simply place an army on the continent and expect success, this strategic pillar required cultivating and cooperating with a host of European allies.

Against this backdrop, the French Revolution initially appeared to be a boon for Britain. Crippled by internal convulsions, London’s long-time foe was left in no position to challenge British power. But the crisis within France soon turned from boon to bane. Once Napoleon surfaced, that same turmoil was transformed into an expansionist impulse that directly threatened Europe and therefore British strategy on land and sea. Napoleon’s dramatic military successes upended the balance of power on the continent and tested Britain’s reliance on naval power.

In the initial stages of the Napoleonic Wars, a stalemate of sorts emerged, where Britain prevailed at sea and France on land. In the course of two major battles, Adm. Horatio Nelson preserved Britain’s naval dominance. In 1798, at Aboukir Bay near the mouth of the Nile River, Nelson and his fleet destroyed 11 French warships. Then off Cape Trafalgar in southwest Spain in 1805, Nelson’s command sunk or captured 19 French and Spanish ships. Not a single British ship was lost in either engagement. But these naval victories did little to help Britain on the continent. Napoleon devasted a combined Austrian and Russian army at the Battle of Austerlitz at the end of 1805. He then repeated this success in 1806 and 1807, first at the expense of Prussia and then by crushing another Russian army.

Britain succeeded in turning the tables on land only with the help of a broad coalition of allies, brought together by British statecraft and Napoleon’s own overreach. Britain also sustained the fight because its economic system offered more to neutral powers and belligerents than Napoleon’s. Napoleon attempted to counter Britain’s advantage by enforcing a continent-wide trade embargo of British goods and by forbidding British access to European ports. It was the effort to enforce this unpopular embargo, the Continental System, that pushed Napoleon to invade Spain and Russia, thereby dooming his empire. When Napoleon occupied Spain in 1808, he prompted an ugly guerrilla war that enabled the British army under the Duke of Wellington to come to the support of the Spanish resistance. Then, more dramatically, Napoleon’s 1812 campaign in Russia destroyed his army.

It was in this context that Britain was able to put together the coalition that eventually brought France down. In the last stages of the Napoleonic empire, Austria, Prussia, and Russia teamed up with a British army advancing from Spain and moved in unison to box in France. Pressuring France on all sides, the allies seized Paris in April 1814 and deposed the emperor. When Napoleon returned from Elba a year later and tried to resurrect his empire, Britain resurrected the same coalition and defeated him again at Waterloo.

Pivot to Asia

So what does this history mean for America’s competition with China today?

The good news is that the United States currently enjoys many of the advantages Britain did. Most importantly, the United States enjoys more support from allies in the Pacific than does China. Traditional allies such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore look to Washington for leadership. Even recent foes such as Vietnam have been turned into partners. While U.S. relations with the Philippines have frayed, a bond endures. Moreover, there are deeply rooted ties between the United States and Australia, and both nations are seeking to forge a new Quad partnership in the Pacific with India and Japan. Certainly, this array of diplomatic successes dwarfs China’s reach across the Pacific.

In the economic realm, the United States also enjoys a similar advantage to what Britain had in its contest with France. It is easy to imagine which would cope better with the interconnected world of today: a closed system seeking economic dominance or an open system attempting to foster economic growth to reward its allies. Washington should build on the benefits of its system — much as Britain was able to do to when facing an authoritarian France.

Like Napoleon, China may discover that its efforts to reverse America’s advantages can backfire. China’s entry into the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership signed in November 2020 will test its compatibility with 15 Asia-Pacific nations, including Japan and South Korea. If they prove incompatible and China takes a more coercive approach, this reaction could actually push countries in the region closer to the United States. And, like Napoleon’s Continental System, China’s One Belt One Road has risks too. This initiative appears to be a far-reaching economic answer to U.S. dominance, a push on land to evade established shipping lanes at sea. But it can also alienate allies. The one-sided nature of One Belt One Road rewards nations for doing China’s bidding with contractual, financial obligations designed to advance subservience, not parity. Moreover, the One Belt One Road initiative has been accompanied by a massive Chinese military buildup to challenge the United States. Yet this military build-up itself risks undermining China’s drive for economic growth.

All these factors mean that it is unlikely China will win its competition with the United States. China is renowned for its long-term strategizing and for thinking 100 years out. Napoleon, too, boasted that he had found the antidote to British supremacy in the future United States. That rising nation, he thought, would someday contest British sea power and trade, opening the way for France to further challenge its rival. Napoleon’s direct contribution to this plan came by way of the Louisiana Purchase, a vast territory comprising about one-third of the size of the present-day continental United States. Of course, with the help of the Louisiana Purchase, the United States eventually became a superpower. But the results were not what Napoleon anticipated, and it was too late for him anyway.

The real risk, by contrast, is that an isolated but expanding China might replicate the other aspects of revolutionary and then Napoleonic France. Should internal woes cripple China, it might lead the regime to embrace expansionist impulses as a means of saving the state. The threat of regime change in China could prompt Chinese President Xi Jinping to play the role of Napoleon in rapid fashion.

No Need for a New Napoleon

This brings us to the most important potential lesson from the Napoleonic Wars. Britain won, but at an enormous cost. The United States still has the potential to avoid war entirely. The United States embraced global hegemony after World War II but lost sight of the need to eventually move toward a balance of power as international circumstances changed. Britain only slowly made this determination when confronting Napoleon, and the result was a long, drawn out war testing British power to the utmost. And even when Britain won, its leaders were quickly forced to side with their recently defeated foe to bring a new balance of power to the continent. A much earlier accommodation with Napoleon may have achieved this same end without the loss of lives and resources. Had Britain been less quick to prioritize economic advancement at Europe’s expense, Napoleon could not have rallied as much European support by claiming to oppose British financial tyranny. Instead, by sharing the bounty of global trade, Britain could have stripped Napoleon of this rallying call and brought the house of Europe down upon him long before 1814.

Rather than pursuing superpower status at the risk of war with China, Washington should learn from this and instead pursue a balance of power. Both sides stand to benefit from greater accommodation. The United States should accept China as a partner in the Pacific. China should reject the lure of global hegemony and accept responsibility for its actions as a regional power. This reorientation would make a balance of power possible and avoid the kind of devastating struggle that defined British and French relations at the turn of the 19th century.

Matthew J. Flynn is a professor of war studies at Marine Corps University. He specializes in the evolution of warfare and has written on topics such as preemptive war, revolutionary war and insurgency, borders and frontiers, and militarization in the cyber domain. The opinions expressed here are his own and do not represent those of Marine Corps University, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.

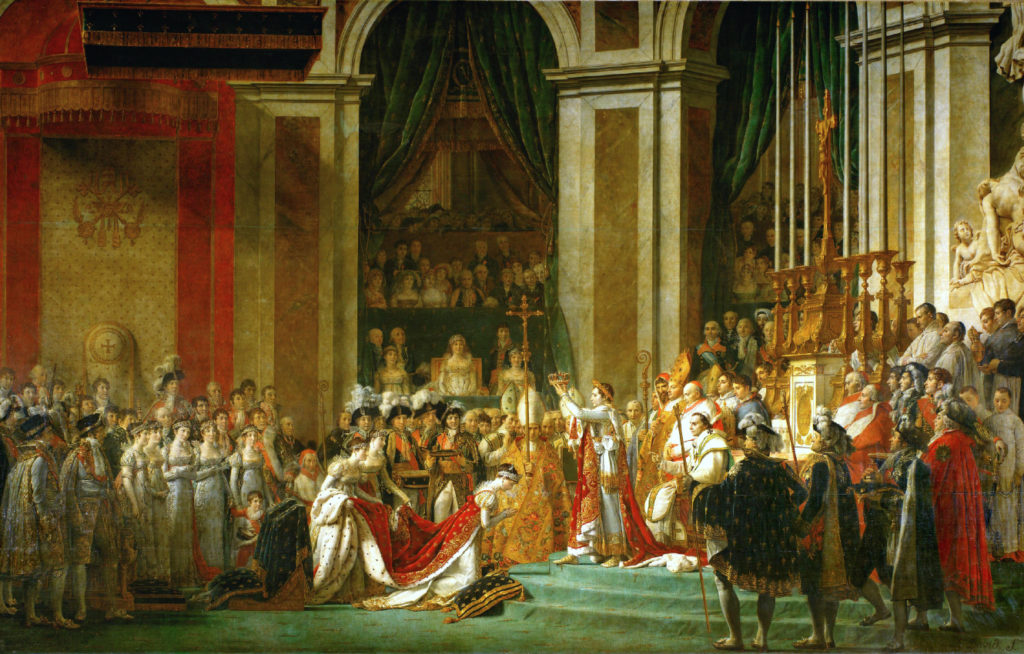

Image: The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David (1804)