China Does Not Have to Be America’s Enemy in the Middle East

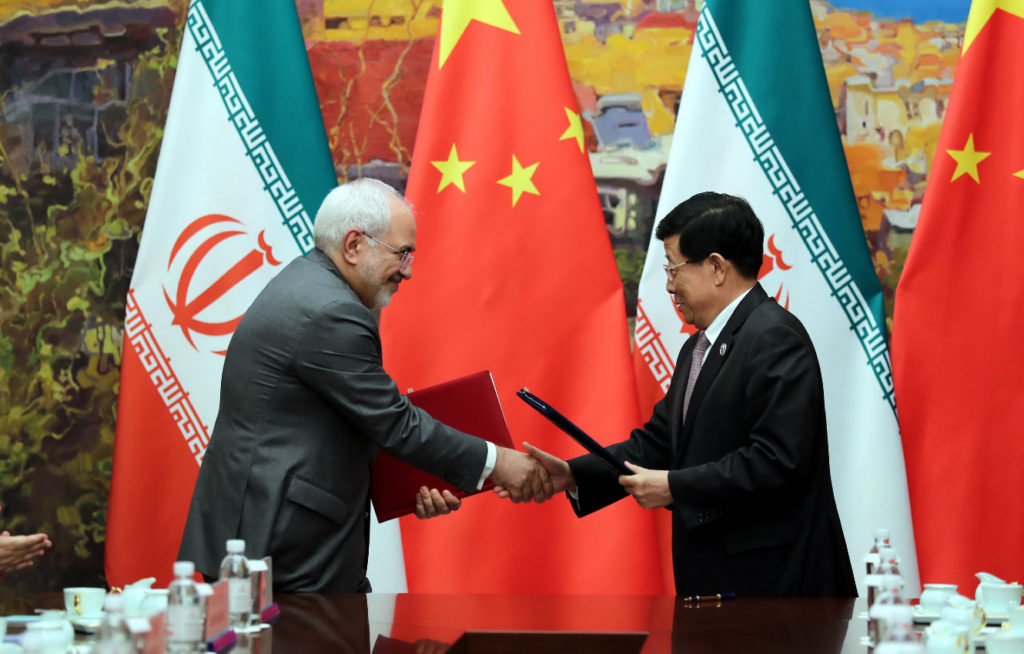

The reporting has been feverish. “China sets sights on Middle East with Iran co-operation deal,” reads a BBC headline. The New York Times reports that “China, with $400 Billion Iran Deal, Could Deepen Influence in Mideast.” Indeed, just in time for the Iranian new year, China and Iran inked a comprehensive strategic partnership deal in which China promised to boost its investment in Iranian infrastructure across various sectors in exchange for a steady supply of oil. With American foreign policy increasingly viewed through the lens of great-power competition with China, it is easy to see how the deal could only be bad news for U.S. interests.

But what’s really going on? Are China and Iran actually joining forces against the United States? Does the recent agreement between Beijing and Tehran signal the start of a new Cold War-style competition in the Middle East? How should U.S. officials think about Chinese influence in the region?

Based on initial reporting, the Sino-Iranian deal is premised on a sizable but unconfirmed amount of Chinese investment in Iran in exchange for a guaranteed and possibly discounted supply of Iranian oil over a 25-year period. If public statements by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi can be taken at face value, the agreement codifies a longstanding informal alliance and lays the foundation for deepened cooperation between the two countries, particularly on the economic front.

But significant Chinese investment in Iran, whatever the scale, does not herald the creation of a “China-Iran axis” as some have posited. Indeed, the level of concern in the United States over this development is overblown and could even be unproductive should it spike U.S. animosity toward China in the region. While China threatens U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific, the United States does not need to consider China an adversary in the Middle East.

Tempting as it may be to brand all Chinese activity as nefarious in nature, China’s actions in the region are not always damaging to U.S. interests. Sometimes, the United States may even find overlapping interests with China given that both countries have a stake in containing conflicts and instability. And, importantly, an uptick in Chinese influence does not necessarily erode U.S. power in the region. As it contends with multiple challenges around the globe, the United States should look for potential opportunities to cooperate with China even as it seeks to compete on other fronts.

China’s Enduring Interest in the Middle East

The deal between China and Iran is not a sudden or unexpected development. China’s involvement in the Middle East has been steadily increasing over the last two decades, and a strategic agreement with Iran has been in the works for years. The U.S. withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal may have further incentivized Iran to expand its relationship with China, but that was likely not the primary catalyst for this tightening in relations. China’s economic boom throughout the 1990s prompted it to turn its attention to the Middle East — both as a source of raw materials to fuel its industrial base and a source of new markets to which it could channel exports.

The Middle East has emerged as China’s most strategically important region beyond its immediate backyard in the Indo-Pacific. It is China’s largest source for oil, of which it consumed 650.1 million metric tons in 2019. But it is Saudi Arabia and Iraq, not Iran, that are China’s largest oil suppliers, accounting for 15 and 9 percent of imports, respectively, in 2019. Iran sent just 17.8 million tons of crude oil to China in 2020 and early 2021, only accounting for about 3 percent of China’s oil imports. (Beijing primarily has its eye on securing Iranian energy resources as a backstop in the event of a conflict with the United States.) The Middle East’s prime location also could provide China with valuable land and sea connectivity to Asia, Europe, and parts of Africa for its Belt and Road Initiative.

Chinese and Iranian officials agree on one important thing: They’d like to sideline U.S. power and influence. Iran opposes the U.S. force presence in the region and supports non-state militia groups that regularly attack U.S. interests, particularly in neighboring Iraq. China, meanwhile, has opportunistically sought to work with any willing partners in the Middle East, regardless of their relations with the United States, in order to deepen its profit and influence.

Limits of Sino-Iranian Cooperation Present Opportunities for Washington

China and Iran do not share enough interests to support an enduring partnership. Iran is just one part of China’s larger interests in the Middle East, and Chinese influence in the region faces some hard limits. China has to balance relationships with multiple countries that don’t see eye-to-eye, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Israel. And China was concerned about a growing anti-Iran regional alignment when Arab Gulf states like the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain agreed to normalize relations through the Abraham Accords. China’s deepening relationship with Israel — which spans diplomacy, trade, construction, education, science, technology, and tourism — creates a particularly difficult context for its expanding relations with Iran.

When assessing the Sino-Iranian relationship, it’s useful to note that Iran is not China’s number one economic partner in the region. China sells more arms to U.S. partners in the Middle East (i.e., Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) than it does to Iran. Iran has never accounted for more than 1.2 percent of China’s total foreign trade volume, behind both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Iran also lags behind the United Arab Emirates as a destination for Chinese foreign direct investment. And Iranians are notably resistant to economic dependence on China and tend to view Chinese products as inferior to Western ones. Indeed, the strategic agreement with China has spurred domestic debate in Iran — and not always in China’s favor.

Not all Chinese economic investments in the Middle East should concern U.S. policymakers. Certainly, some could be used to undermine U.S. interests — China’s pursuit to embed surveillance technologies in so-called “smart cities,” for instance, has worrying implications for human rights throughout the Middle East. But other investments (e.g., in infrastructure, development, and reconstruction) may spur regional growth. Rather than expend energy and scarce resources on infeasible goals such as trying to “push” China out of the region, the United States might try to mitigate the negative aspects of China’s involvement and rebalance its own investments in these areas.

Looking Ahead

The recent deal between China and Iran is likely not a game-changer for the United States, and a Cold War-like rivalry with China in the Middle East isn’t a foregone conclusion. Ultimately, China needs the Middle East to remain stable to feed its oil dependence and reap any rewards from its investments. As a result, the United States might even find opportunities to cooperate with China in the region, even while competing elsewhere.

For instance, China and the United States can cooperate on advancing nonproliferation objectives in the Middle East. Neither country would benefit from Iran developing nuclear weapons, which would raise tensions and could cause a regional arms race. For its part, China showed no signs of resisting renewed nuclear diplomacy in Vienna as the Biden administration seeks a U.S. return to the Iran nuclear deal in a compliance-for-compliance arrangement. Likewise, neither country has an interest in prolonging devastating civil wars in the Middle East or permitting escalation of maritime conflicts that can disrupt global shipping. Humanitarian aid and disaster relief operations and antipiracy patrols present further opportunities for cooperation in the Middle East. There might even be space for cooperation in counter-terrorism efforts specific to that region given Beijing’s professed concerns about the threat global terrorist networks pose to its expatriates and investments abroad. But such potential cooperation would have to be carefully considered given China’s expansive view of the proper use of “counter-terrorism,” most particularly its current persecution of innocent Uyghur civilians in its own country, including mass incarceration of an estimated 1 to 1.5 million people.

U.S. policymakers may find it worthwhile to consider a set of reimagined policy choices in the Middle East, including being strategic about where and how to confront China and leaving openings for cooperation with its global competitor when interests overlap. Doing so will be politically difficult, especially given how unpopular China and Iran are on Capitol Hill and elsewhere. Nevertheless, U.S. officials should remember that not every move by China in the region will undermine American geopolitical interests. Instead, Washington should have a clear-eyed view about what it seeks to accomplish in the Middle East and defend those interests vigorously, but it should also work with China in the region when it’s useful to do so.

Ashley Rhoades is a defense analyst at the RAND Corporation. Dalia Dassa Kaye is a fellow at the Wilson Center and the former director of the RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy. They are co-authors of a new RAND report, Reimagining U.S. Strategy in the Middle East.