China and COVID-19 in Saudi Media

“China is the only country that has performed well in dealing with this crisis,” declared Saudi-owned broadcaster Al-Arabiya in a March review of China’s COVID-19 efforts. While nominally independent, the station — reportedly taken over by the Saudi the royal court in 2014 — tends to reflect official Saudi views. These views can change, however. In an April segment that covered mounting criticisms of Beijing, presenter Rufaydah Yassin commented that “it appears that China’s efforts to market its successes with regard to the coronavirus have not yet panned out.”

In the initial weeks and months of the pandemic, a wide range of Saudi outlets offered favorable reviews of China’s response, while finding little to praise about U.S. efforts. These discussions in Saudi Arabia, a close security partner of the United States with considerable press censorship, provide evidence of the damage done to U.S. standing abroad by its “America First, America Only” approach to the crisis, and of the abysmal performance of its government at home.

However, China’s mixed record in boosting its image in Riyadh is a reminder that soft-power competition is not a zero-sum game. Even as Saudi outlets have grown more willing to air criticisms of China, some have derided the efforts of President Donald Trump and his administration to blame COVID-19 on Beijing.

“Blaming China” is a convenient electoral strategy but an ineffective foreign policy, with considerable downsides. If Washington wants to maintain its international standing amid COVID-19 — including in places like Saudi Arabia — it needs to focus first on containing and responding to the virus at home, rather than lodging accusations abroad. The United States should do what it can to facilitate a capable domestic response to the pandemic, while affording its diplomats the funding and political cover needed to offer small but symbolic forms of public health assistance overseas.

Initial Praise for China’s Apparent Success

Within Saudi Arabia, media commentary initially highlighted China’s successes in containing the virus. They cited Wuhan’s strict social controls while avoiding discussion of the lies and lack of transparency from the Chinese government that allowed the virus to spread in the first place. Although media commentary cannot be taken as a direct expression of views by Saudi officials, these statements and articles do reflect the bounds of acceptable public discourse, and as such, an indirect reflection of official sympathies with the Chinese model of durable “upgraded” authoritarianism.

Top columnists in Al-Sharq al-Awsat, a widely-read paper owned by King Salman and his immediate family, offered support for China’s strict social controls in containing the pandemic. On March 16, Salman al-Dosary, former editor-in-chief of the paper, praised China’s success in employing strict quarantines to “lay siege to the disease.” Al-Dosary, along with many Saudi writers, further sought to identify the Saudi government’s response to China’s as an example of decisive action to contain the virus.

Others made it clear that strict controls needed to be backed by a threat of force to keep citizens in line. “The U.S. government does not have enough military force to keep ten million people [in New York] at home, unlike China,” noted Abdel-Rahman al-Rashed, another longtime media figure who is said to be close to the Saudi Royal Court, on April 9. “If China had not done so [in Wuhan], the number of those affected would be in the tens of million.” He also encouraged readers earlier in March to focus on resolving the crisis rather than assigning blame. “Maybe it started in a country before China, but its origin does not concern us as much as overcoming it and returning to ‘normal’ life.”

Evolving Saudi Coverage of China

While favorable views of China’s example of authoritarian rule amid state-led development are hardly new in Saudi Arabia’s media and commentary, these perspectives have historically been balanced by criticisms of China’s “godless” communist ideology and its hostility towards the practice of Islam within its borders. Yet as the two countries’ economic relationship has strengthened, even as the Saudi monarchy de-emphasizes Islamic credentials in its claims to authority, critical views have largely disappeared from the Saudi press.

Mohammed Al-Sudairi, Saudi expert on Sino-Middle Eastern relations, noted in 2013 an “avid admiration” by many Saudi commentators for China’s “economic miracle.” Writing on the occasion of the 2010 Shanghai expo, Saudi columnist Mohammed al-Makhlouf highlighted China’s “enormous strides” in economic development. This article was carried by Al-Watan, a more populist broadsheet that has occasionally championed issues of social or political reform in the kingdom.

In years past, however, this admiration was tempered by concerns about China’s treatment of Muslim minorities — an area of particular concern for citizens of a kingdom that claims leadership of the Muslim world. Despite official silence over a 2009 crackdown on protests and riots by China’s Uighur Muslim minority, Saudi newspapers helped spur popular outrage over treatment of Muslims within China.

Others focused on Chinese repression more broadly. “Chinese citizens cannot object to [state repression] in a country that executes five thousand of its citizens every year, some of them for minor crimes such as tax evasion,” noted Muhammad Alwan in 2011, also for Al-Watan. This pushback contributed to Saudi views of China that were unusually unfavorable for the Arab world.

However, with the recent rise to power of Saudi Arabia Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, criticism of China (among many other topics) has been muted. This reflects a shrinking sphere for political commentary as well as repression of all forms of political Islam within the country.

The Chinese government has thus found a more receptive audience for its efforts to normalize the repression of Muslim minorities as it emphasizes a shared interest of Chinese and Arab autocrats in the subjugation of potentially threatening populations. Indeed, Muhammad bin Salman emphasized China’s “right to carry out anti-terrorism and de-extremisation work” in reference to the country’s crackdown on ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region.

Still, there has been some leeway for Saudis to criticize China’s handling of the pandemic, particularly on social media, but only when it avoids religious interpretations of China’s culpability. Several Saudi individuals have reportedly been arrested for the kind of “divine-punishment” explanations that led some in the Arab world to argue that China’s affliction with the virus results from its government’s mistreatment of Muslim minorities.

Saudi businessman Hussein Shobokshi faced no repercussions, however, for predicting that China would face “difficult” times in being held accountable for the pandemic. Another Twitter influencer, who initially hyped conspiracies of biological warfare being responsible for the virus, charged China with being “a threat to the health of the world” in a racialized attack.

Authoritarian Admiration

The bulk of Saudi commentary in March, however, was not shy about identifying the authoritarianism of the Chinese regime — and, by extension, the harsh measures taken by Saudi Arabia’s absolute monarchy — as a decisive factor in effective COVID-19 responses. Saudi columnists for a more nationalist daily, Okaz — a platform known for frequent conspiratorial accusations along with occasional (and extremely subtle) critiques of state policy — lauded the Chinese response for, among other factors, being free of “political quarrels and partisan controversy.” Others noted that Beijing’s evidently successful management of the crisis lent credibility to China’s efforts at garnering soft power in the region.

These comparisons (largely sidestepping successful responses in democracies like Germany, Japan, or South Korea) feed into a regular line of Saudi commentary — criticism of “Western” notions of human rights and political freedoms. Salman al-Dosary argued that Western democracies’ ineffective responses to COVID-19 was a function of their inability to limit citizens’ freedoms, stating, “The world has discovered that the same principles that protect public freedoms are the same ones that stand unable to protect lives.” European nations have come under particular criticism, with Okaz writer Hamood Abu Taleb accusing the states of the “old continent” of suffering from a different terminal illness — resting on their laurels rather than striving to address new social challenges.

Some of Okaz’s columnists have even adopted the fringe conspiracies popular on Chinese social media, such as the idea that Italy — rather than China — is the true source of the COVID-19 outbreak. “What if it is proven beyond any doubt that COVID-19 is not from China, but that China simply discovered it and helped the world to confront it? Will anyone doubt that China will then be the leader of a new world?” opined Hani al-Dhaheri, one of the paper’s most pugnacious writers.

These media narratives have no doubt been helped along by an effective Chinese public-relations campaign, including collaborations between the China Media Group and outlets across the Arabic-speaking world. China’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Chen Weiqing, has been active on Twitter, promoting Saudi-Chinese solidarity and highlighting instances of Saudi-Chinese medical collaboration to understand and contain the virus. The ambassador has also drawn attention to his Arabic-language appearances on Saudi television shows to explain the Chinese government’s COVID-19 response.

In print media, the consul general of China in Jeddah, Tan Banglin, listed off China’s efforts to contain the virus in an Okaz op-ed, while criticizing those who have wasted time “smearing the reputation of China.” Ambassador Chen gave an interview to the more established Al-Riyadh, emphasizing the importance of trade ties with the kingdom and highlighting China’s efforts to assist in combatting the virus around the world.

This messaging comes against a backdrop of limited but meaningful cooperation between China and Saudi Arabia with regards to COVID-19, as was seen with Saudi Arabia sending a shipment of aid to Wuhan, China (the epicenter of the outbreak) in early March. At the same time, the Chinese ambassador to Saudi Arabia was meeting with the Gulf Cooperation Council to share some of the Chinese government’s accumulated knowledge about the virus. Saudi Arabia also took part in a video conference between Chinese health officials and their counterparts across the Middle East and North Africa.

Whither the United States?

By contrast, U.S.-Saudi cooperation in response to the pandemic appears to have been almost nonexistent. Washington’s primary concern in the bilateral relationship appears to be the falling price of oil. Trump’s priority with respect to the kingdom has been to pressure Saudi leaders to rescue U.S. shale producers from low oil prices, either through unilateral cuts or in cooperation with other producers. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has only mentioned the pandemic in passing before pressing Saudi counterparts on the importance of stabilizing global energy markets. The United States has even undermined Saudi efforts to coordinate greater support for the World Health Organization via the G-20 (which the kingdom currently heads), with Trump suspending payments to the World Health Organization outright.

Washington has largely been spared Saudi criticism, official or otherwise, because of an effective cordon sanitaire in Saudi media around the Trump administration. Saudi authorities are likely aware that they will never deal with a more favorable U.S. leader than Trump, who has consistently blocked or blunted U.S. domestic criticisms of Riyadh. In particular, Trump has wielded presidential vetoes to defend arms sales to the Saudi Arabia against bipartisan legislation, going against Congress and an American public deeply skeptical of arms sales abroad. Saudi officials lobbying for Washington are also unlikely to find a more cooperative counterpart than the president’s advisor and son-in-law Jared Kushner.

While few have gone as far as Muhammad al-Sa‘id in predicting that Trump will emerge from the crisis as the “Abraham Lincoln of the age,” most Saudi commentators have shied away from suggesting that his administration might be to blame for the course of the pandemic in the United States. Abdelrahman al-Rashed excused the slow U.S. response on the basis of “the limited power of the federal state,” while sympathizing with right-wing conspiracy theories in the United States that much of the suffering caused by the virus is a hoax aimed at attacking Trump.

Even in a sympathetic media environment, American efforts at public outreach reflect a persistent underinvestment in its diplomatic capacity compared with Chinese policies. Messaging out of the U.S. embassy in Riyadh has centered around rote repetition of centrally produced content, such as tweeting out an article highlighting the efforts of American distilleries to combat COVID-19 to followers in the nominally dry kingdom. Filling positions that require advanced Arabic-language skills is a constant struggle, making engagement with local media outlets an uphill battle; the U.S. ambassador to Riyadh has thus far only conducted one short interview (even shorter on specifics) with Okaz. This contrasts with a heavy emphasis on regional and language expertise in the Chinese diplomatic corps.

Narratives Without Works Are Useless

Some analysts, like the Hudson Institute’s John Lee, have stressed that this war of narratives is where the United States needs to focus in attention to maintain its standing on the international stage. Yet this underestimates how much U.S. credibility on this issue has been undercut by its failure to mount an effective response at home and abroad. Other experts, like Jonathan Fulton of Zayed University, have argued that China’s effective messaging and outreach have raised its standing among the Gulf monarchies. This is true to an extent, but it overestimates the credibility of Chinese messaging amid new revelations of its COVID-19 obfuscations.

Commentary in Saudi Arabia exposes the folly of official American messaging on COVID-19, which focuses on pinning the blame for the pandemic on China. American criticism of Beijing rings hollow given the obvious failure of the U.S. government to marshal an effective pandemic response within its own borders. For one, China’s initial messaging was rendered credible by its past track-record of state-led development. “Perhaps the successes declared by China are exaggerated or government propaganda,” Abdelrahman al-Rashed conceded on March 30, “but the numbers of its achievements in a decade and a half do not lie.” At the same time, China’s own failings have attracted increasing attention in all but Saudi Arabia’s most avowedly pro-China outlets. Articles in Okaz have increasingly highlighted China’s manipulation of COVID-19 statistics; Abeer al-Fawzan accused China of “attacking the whole world” and Tariq al-Hamid referenced “doubts about [China’s] credibility” in respective op-eds.

Furthermore, even as China falters in its efforts to make soft-power inroads with like-minded autocracies like the Gulf monarchies, the United States will not automatically benefit. Saudi commentators are certainly aware of the Trump administration’s efforts to brand COVID-19 as “the China virus,” but strategic communications in the absence of concrete action damages American credibility. “On social media, the amplified news of the medical achievements and successes from China is matched by a deliberate smear campaign from the United States,” observed Abdelrahman al-Rashed in Al-Sharq al-Aawsat.

Al-Riyadh, probably the most pro-China of Saudi outlets, made no mention of China in a recent editorial on “decisive responses” to the pandemic. Yet it all but mocked Trump and Pompeo for “contenting themselves [in their COVID-19 response] with calling the epidemic the ‘Chinese’ virus” rather than giving the crisis the attention it deserved. Likewise, Al-Sharq al-Aawsat afforded Hussein Shobokshi space to further criticize China’s response, which he compared with the successful democratic model of the Republic of China (no mention of the United States).

Regardless of China’s actions, U.S. domestic failures and an underwhelming diplomatic response the pandemic only reinforce the idea that the United States is both unwilling to provide a semblance of global leadership and unable to set much of an example for other countries to follow. “The West has not shown a itself as a shining example of conduct towards the virus,” noted former Saudi intelligence director Turki al-Faisal in an interview published April 5. “Nor have China, Russia, and Iran.”

A New Approach?

Instead of engaging in a war of words with China, the United States should improve its domestic response to the pandemic and find new ways to deepen international cooperation. At a minimum, regaining the standing to offer credible advice or criticism about the COVID-19 pandemic requires a more effective U.S. response domestically. Foreign audiences are likely to see efforts to cast blame on China as a way to deflect attention from the denial and dysfunction that has plagued the Trump administration’s response to COVID-19.

For now, though, policymakers concerned with shoring up U.S. foreign relations with key states like Saudi Arabia should start with small efforts towards cooperation at the margins — convening information sessions with U.S. health experts, for example, or finding new ways to support global academic and cultural exchange. China’s support for Saudi Arabia amid the COVID-19 virus has been quite limited, yet it compares favorably with the practically nonexistent U.S. engagement. Unfortunately, the Trump administration’s recent decision to defund the World Health Organization suggests that the diplomatic dimension of Washington’s pandemic response may get worse before it gets better.

Andrew Leber is a PhD candidate at Harvard University’s Department of Government, where he researches Saudi policymaking in labor-market reform and regional development. He is on Twitter at @AndrewMLeber and occasionally blogs about Saudi media at “The Bitter Lake.”

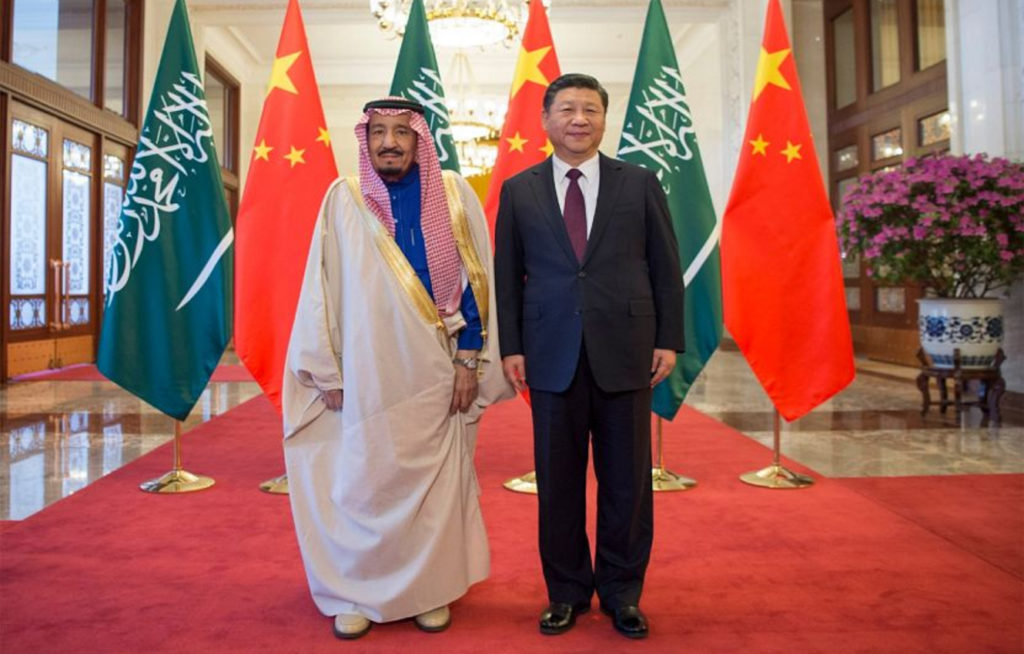

Image: Saudi Press Agency