‘Quality Infrastructure’: Japan’s Robust Challenge to China’s Belt and Road

Editor’s Note: This is the 26th installment of “Southern (Dis)Comfort,” a series from War on the Rocks and the Stimson Center. The series seeks to unpack the dynamics of intensifying competition — military, economic, diplomatic — in Southern Asia, principally between China, India, Pakistan, and the United States. Catch up on the rest of the series.

Italy recently became the first major European economy to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the massive program to finance and build “connectivity” infrastructure across Eurasia. This development served as a reminder that the initiative remains a major source of controversy even as it could cement China’s status as the center of gravity of the world economy for decades.

However, while China seeks to extend the Belt and Road Initiative to new members and fend off concerns about its lending practices, it faces a capable rival in its own backyard for infrastructure investment in South and Southeast Asia. For the past seven years, Japan has competed against the Chinese initiative, not only by reforming its lending practices and increasing funding for development assistance, but also by articulating a vision for what Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has called “quality” infrastructure investment and seeking international partners to advance these principles.

Japan has acknowledged that it cannot prevent China from using its economic might to help the region’s middle-income countries meet their infrastructure needs. Yet by articulating new principles for investment, enlisting new partners, and bolstering its financial commitments, Japan has developed an alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative that could limit developing countries’ dependence on Chinese lending. These efforts could even influence China’s own practices, as Japan has made its quality infrastructure program the basis for bilateral development cooperation with China.

Abe’s approach to meeting Asia’s “infrastructure gap” looks increasingly like the gold standard, making Japan an essential player in financing and building the infrastructure Asia needs to grow. Japan’s methods should serve as a model for U.S. policymakers for more constructive economic engagement in the region, which will be necessary if the United States is going to have staying power in the competition for influence with China.

Japan and regional development

Decades before the recent vogue for economic statecraft, Japan pioneered the use of foreign investment and development assistance to advance its national interests. Since Japan emerged from the U.S. occupation after World War II, it has used the tools of economic diplomacy to promote the development of non-communist Asia in order to strengthen its own economic prospects. Japan’s postwar approach to reparations, official development assistance, and public-private investment in Asia’s developing countries arguably anticipated what China is trying to accomplish through the Belt and Road Initiative. Tokyo recognized that promoting industrialization in Asia’s less-developed countries — particularly by building energy and connectivity infrastructure — could create market opportunities for Japanese firms, strengthen political influence in strategically valuable countries, and facilitate resource-poor Japan’s access to energy and other natural resources needed to fuel high-speed growth. As articulated in the “flying geese paradigm” of development, Japan would help its neighbors transition to more lucrative industrial sectors and, in the process, grow wealthier itself.

While Japan’s “lost decades” and China’s rise have led most observers to overlook Japan’s role in Southeast and South Asia, the country has remained an important source of development assistance, public lending, and private investment across the region, particularly as Japanese companies have extended their supply chains deeper into Asia. At the end of 2016, Japan’s stock of foreign direct investment in major Asian economies (excluding China and Hong Kong) was nearly $260 billion, exceeding China’s $58.3 billion. It is undeniable that Japan has increasingly had to jockey with China for high-profile projects as China’s footprint across Southeast and South Asia has grown. But Japan’s longstanding relationships and its long record of private and public investment across the region make it a worthy competitor with China.

Abe pursues “quality infrastructure” investment

Japan beat the Belt and Road to the punch not only by advancing and financing a large-scale Asian connectivity endeavor, but also by emphasizing the role of quality for more sustainable growth. Japan’s financial position in Asia provided a solid foundation for an upgraded approach to infrastructure investment. Even before President Xi Jinping unveiled what would later become the Belt and Road Initiative in late 2013, Abe signaled his government’s intentions to develop a new approach to infrastructure investment as part of his “Abenomics” program.

In March 2013, the Abe administration established an advisory council to develop a strategy for infrastructure exports and create new tools for supporting Japanese exporters. But as Japan developed its strategy and as the scale of China’s investments became apparent, Abe began articulating a new line: “quality infrastructure.” In order to compete with China, support new growth opportunities for Japanese companies, and promote regional development, the Japanese government promulgated a new set of principles to guide its public investments and its support for private investment while also increasing the scale of its investments. “Quality” investment means considering a wide range of factors when making investment decisions, including environmental and social impact, debt sustainability, the safety and reliability of the construction, and the impact on local employment and technical expertise.

In 2015 and 2016, the Abe government issued a series of policy statements that amounted to a comprehensive new approach to Japan’s infrastructure investment and development across Asia. First, in the February 2015 revision of Japan’s Development Cooperation charter, the administration called for “quality growth,” meaning growth that is inclusive, sustainable, and resilient. Japan would focus on “physical and non-physical infrastructure including that which is needed for strengthening connectivity and the reduction of disparities both within the region and within individual countries” and help Southeast Asian countries escape the “middle-income trap,” something China is struggling to do itself.

Three months later, the government announced the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, by which Japan would increase its investment in Asian infrastructure to ¥13.2 trillion (roughly $116 billion in current U.S. dollars) between 2016 and 2020, a 30 percent increase over the previous five-year period. The partnership included reforms to streamline the process of making loans and provide additional guarantees against losses to encourage private companies to participate in infrastructure projects.

The Abe administration would further refine this program in 2016, when, as the chair of the G7, it unveiled the “High-Quality Infrastructure Export Expansion Initiative.” From 2017 onward, Tokyo would nearly double its annual support for infrastructure exports from ¥110 billion to ¥200 billion (roughly $1.8 billion in U.S. dollars), make it easier to secure loans denominated in yen and possibly also in euros, and increase Nippon Export and Investment Insurance’s coverage for overseas projects to 100 percent.

As a result of these initiatives, Japan — still, after all, the world’s third-largest economy — remained a major alternative source of development finance even as China ramped up the Belt and Road Initiative and stood up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. As Abe himself suggested when he announced the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, Japan was not calling on Asian countries to reject China but rather offering an alternative source of funding (and set of principles) for filling the region’s infrastructure gap. “We should seek ‘quality as well as quantity,’” he said in May 2015. “Pursuing both ambitiously is perfectly suited to Asia.” In other words, as the Obama administration was struggling to keep U.S. allies from joining China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Congress was letting the U.S. Export-Import Bank’s charter expire, Japan was opposing the Chinese initiative but also significantly upgrading its tools for economic statecraft.

Internationalizing “quality infrastructure”: co-optation, not competition

The Abe administration has not only articulated its approach to infrastructure finance and ramped up its lending, it has also sought to export its “quality infrastructure” concept.

Japan and India have made the concept a central theme in their bilateral relationship and, increasingly, their cooperation in other countries. Abe has built on a longstanding affinity for India — the Indo-Pacific concept was arguably born from Abe’s “Confluence of the Two Seas” address before India’s Parliament in 2007 — to forge closer political, military, and economic ties between the two Asian democracies. Growing Japanese investment in India’s economy has complemented closer links between the two governments and India has consistently been among the largest recipients of Japanese official development assistance, totaling $1.8 billion in gross disbursements in 2016.

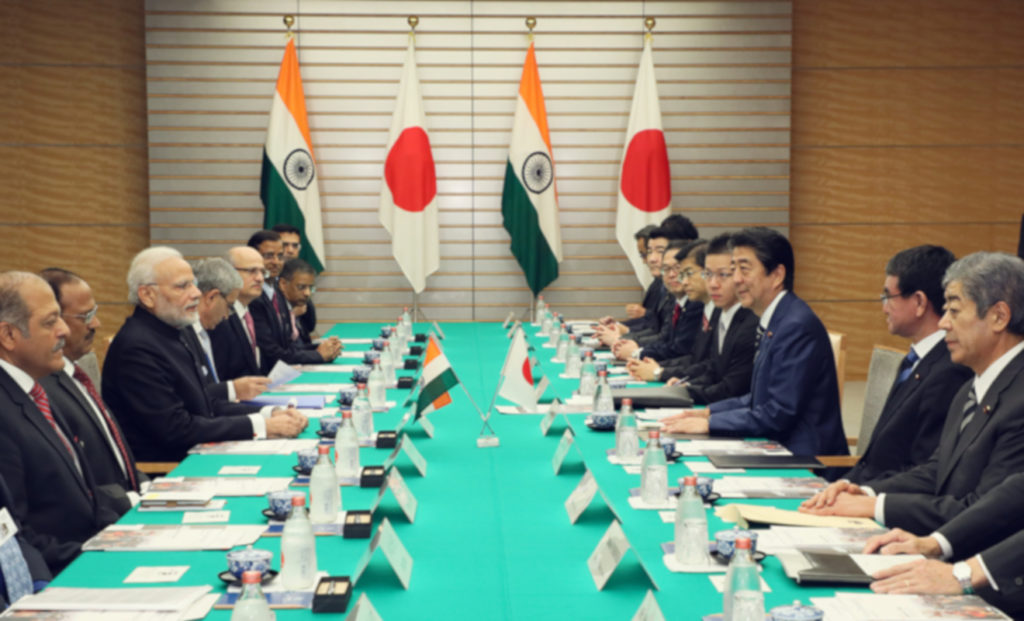

But it was in 2017 that Tokyo and New Delhi placed “quality infrastructure” at the center of their bilateral relationship. When Abe visited India for a three-day trip that included Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home province of Gujarat, Abe and Modi signed a joint statement that strongly endorsed the principles of quality infrastructure investment. They also signed a long list of memoranda regarding Japanese investments in Indian growth according to these principles. These projects included infrastructure development in India’s northeast (which, following the military confrontation between India and China at Doklam, was opposed by China); rail projects, including the Mumbai-Ahmedabad high-speed rail and a technical assistance program sponsored by the Japan International Cooperation Agency for the National High Speed Rail Corporation; subway projects in six major cities; and energy, sanitation, and “smart city” cooperation. Abe and Modi also agreed to work together to use quality infrastructure investment to integrate the Indian Ocean basin, building up “connectivity infrastructure” to link Asia with the east coast of Africa through the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (although the corridor is still an abstract concept, and both governments may be de-emphasizing the idea.)

Perhaps counterintuitively, Japan also cooperates with China on infrastructure investment in third countries. Abe has explicitly framed his government’s talks with China on infrastructure cooperation as a bid by Japan to internationalize “quality infrastructure” principles through cooperation with and perhaps even the conversion of skeptical partners. As Abe said in December 2017, “Under this Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy, we believe that we can cooperate greatly with the Belt and Road plan touted by China.” In the months since the Abe government began talking with China about cooperation on the Belt and Road Initiative, Japan has made clear that any official support would be limited and conditional, dependent on projects satisfying the “quality infrastructure” principles.

As a further indication of how Japan is prepared to use cooperation with China to advance its own priorities, the phrase “Belt and Road” has increasingly given way in bilateral communiqués to the vaguer “cooperation in third countries.” (For example, new vehicles for promoting private-sector cooperation have been given the unwieldy names of the Committee for the Promotion of Japan-China Business Cooperation in Third Countries and the related Japan-China Third Country Market Cooperation Forum.)

To be sure, advancing Japan’s vision for infrastructure investment is not the sole reason for Abe’s outreach to China. Japanese corporations, for instance, have been particularly eager to tame the intense competition with China for big-ticket projects and participate in profitable Belt and Road projects. Still, Abe’s pursuit of cooperation with China highlights the fact that “internationalizing” quality infrastructure investment is a crucial part of Japan’s regional development strategy. Given the size of Asia’s infrastructure gap, if China is willing to aspire to higher standards that are more sustainable fiscally, environmentally, and socially, everyone wins (although Japan could possibly face even fiercer competition to land high-prestige projects).

What the United States can learn from Japan

In November 2018, development finance institutions from Japan, the United States, and Australia signed a memorandum of understanding on infrastructure investment. In the context of Japan’s ongoing efforts to promote “quality” infrastructure investment, this memorandum should not be viewed as a bid to sharpen competition between China and the Quad (Japan, Australia, India and the United States). Rather, it is another step toward making Japan’s principles the gold standard for regional development, particularly as the United States ramps up its development assistance after President Donald Trump signed the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act. Once implemented, the legislation would create a new United States International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC) to streamline the management of development finance. As the United States increases its lending and pursues new opportunities for cooperation with other Indo-Pacific democracies on infrastructure development, there are three lessons the Trump administration can learn from Japan.

First, as the BUILD Act acknowledges, it is impossible to beat something with nothing. If the United States wants to provide Asian countries with an alternative to Chinese investment, it needs to be willing to spend the money, whether directly on loans and equity investments in emerging-market economies or indirectly on insurance to private businesses to minimize the risks of investment. The new USIDFC will have $60 billion to invest, up from the $29 billion allocated to its predecessor, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, though not all of this will go to Asian projects. While these funds may not match the resources China has committed to overseas investment, the funding does signal that the U.S. government, including Congress, recognizes that it needs to be willing to commit more public money to Asia’s infrastructure gap.

Second, the United States, like Japan, should articulate the principles that will guide its commitment to the region rather than launching rhetorical broadsides against the Belt and Road Initiative. The backlash against the initiative across the region suggests that China’s neighbors are capable of figuring out the risks and dangers of Chinese investment — and pushing back against them — for themselves. China may already be scaling back its ambitions in the face of criticism at home and in borrowing countries. The United States should take this as an opportunity to articulate its own principles and offer Asia’s middle-income countries a meaningful choice without forcing them to pick a side.

Finally, Japan’s engagement with China to encourage it to embrace higher standards suggests that at least in some areas, it is still appropriate to cooperate with China to nudge it toward acting as a “responsible stakeholder.” Notwithstanding the concerns about China’s lending practices, Chinese investment can make a real difference for poor and middle-income countries, and in any case it is unlikely that the United States and its allies could push China out of development finance altogether. Therefore, the United States should be more welcoming of China’s willingness to promote the economic development of its neighbors and seek opportunities to shape its development strategy away from financially unsustainable, environmentally harmful, and economically dubious investments. Maybe the United states and other countries will only be able to influence China’s efforts on the margins, but, as Japan shows, even limited engagement could challenge China and its businesses to aspire to higher standards.

Both the BUILD Act and the November U.S.-Japan-Australia memorandum suggest that the Trump administration is increasingly willing to compete with China by offering Asian countries more freedom of action as they pursue economic development. Indeed, the United States can and should upgrade its approach to infrastructure investment and development across the Indo-Pacific region. But the reality is that Japan, with its willingness to invest and its extensive relationships across South and Southeast Asia, will likely continue to be the Quad member spearheading efforts to promote quality infrastructure investment. Still, if the United States can learn from the Abe administration’s example, it may make cooperation between the United States and its regional partners more effective as American leaders seek to promote economic development in the Indo-Pacific region in a free, open, and sustainable manner.

Tobias Harris is a senior vice president and Japan analyst at CEO advisory firm Teneo and economy, trade, and business fellow at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA.