How Does the Next Great Power Conflict Play Out? Lessons from a Wargame

The United States can win World War III, but it’s going to be ugly and it better end quick, or everyone starts looking for the nuclear trigger.

That is the verdict of a Marine Corps War College wargame I organized that allowed students to fight a multiple great state conflict last week. To set the stage, the students were given an eight-year road-to-war, during which time Russia seized the Baltics and all of Ukraine. Consequently, the scenario starts with a surging Russia threatening Poland. Similar to 1939, Poland became the catalyst that finally focused NATO’s attention on the looming Russian threat, leading to a massing of both NATO and Russian forces on the new Eastern Front. China begins the scenario in the midst of a debt-related financial crisis and plans to use America’s distraction with Russia to grab Taiwan and focus popular discontent outward. And Kim Jong-un, ever the opportunist, decides that the time has arrived to unify the Korean peninsula under his rule. For purposes of the wargame, each of these events occurred simultaneously.

Investing for War

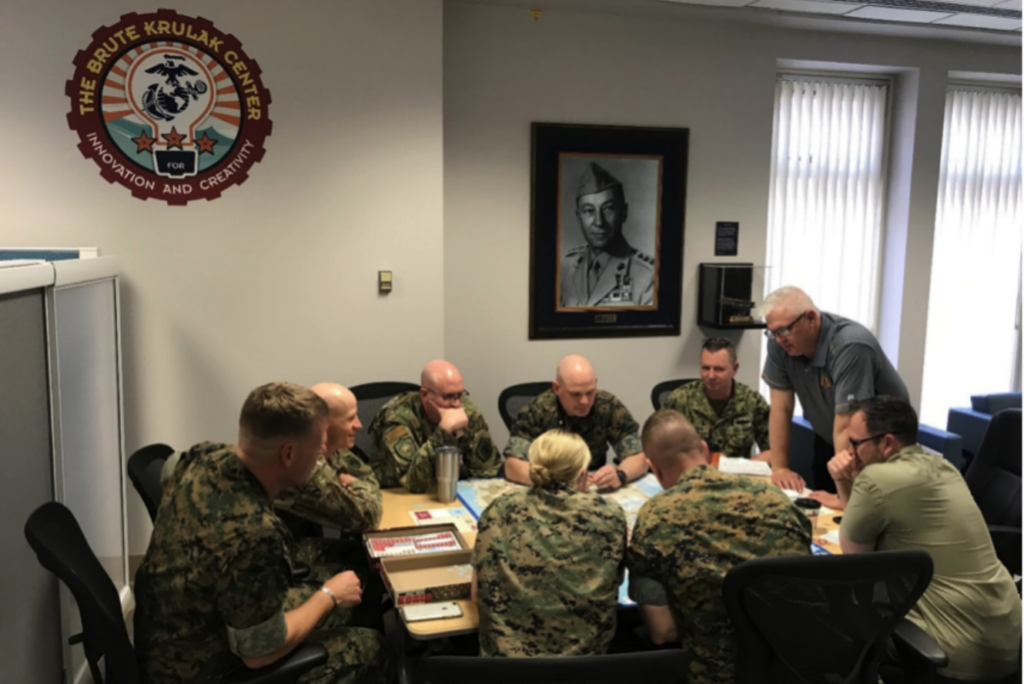

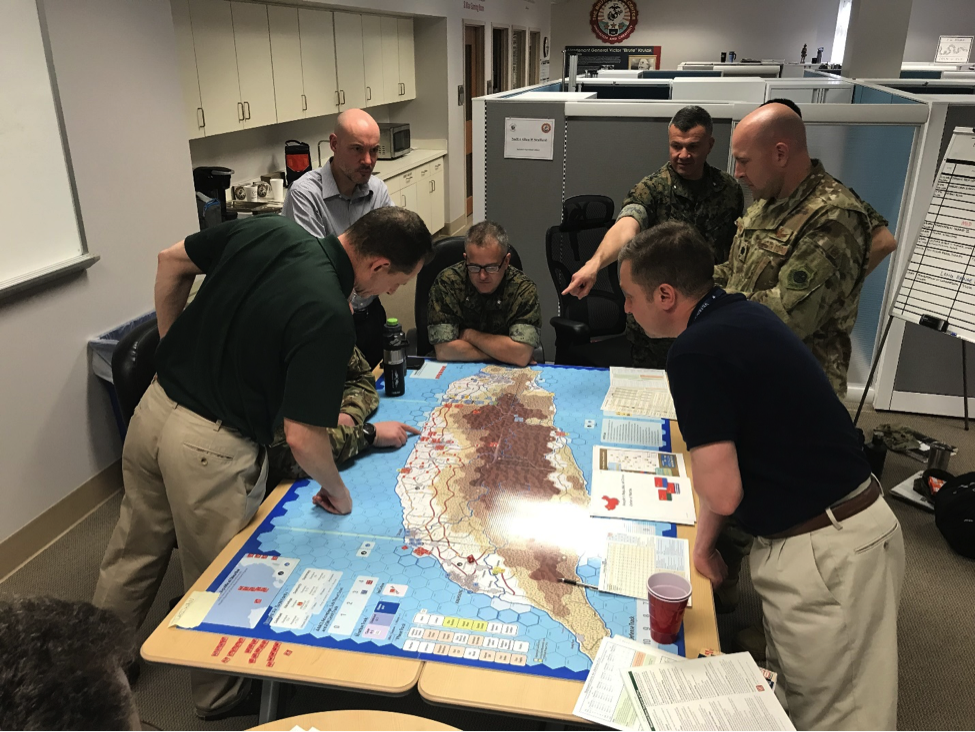

The wargames were played by six student teams, or approximately five persons each. There were three red teams, representing Russia, China, and North Korea; combatting three blue teams representing Taiwan, Indo-Pacific Command (Korea conflict) and European Command. All of these teams were permitted to coordinate their activities both before the conflict and during. Interestingly, although it was not part of the original player organization the Blue side found it necessary to have a player take on the role of the Joint Staff, to better coordinate global activities.

Prior to the wargame, the students were given a list of approximately 75 items they could invest in that would give them certain advantages during the game. Nearly everything was on the table, from buying an additional carrier or brigade combat team, to taking a shot at getting quantum computing technology to work. Each team was given $200 billion dollars to invest, with the Russians and Chinese being forced to split their funding. Every team invested heavily in hypersonic technology, cyber (offensive and defensive), space, and lasers. The U.S. team also invested a large sum in directed diplomacy. If they had not done so, Germany and two other NATO nations would not have shown up for the fight in Poland. Showing a deepening understanding of the crucial importance of logistics, both red and blue teams used their limited lasers to defend ports and major logistical centers.

Because the benefits of quantum computing were so massive, the American team spent a huge amount of its investment capital in a failed bid for quantum dominance. In this case, quantum computing might resemble cold fusion — ten years away and always will be. Interestingly, no one wanted another carrier, while everyone invested heavily in artificial intelligence, attack submarines, and stealth squadrons. The U.S. team also invested in upgrading logistics infrastructure, which had a substantial positive impact on sustaining three global fights.

Early Strategic Decisions

As there was not enough American combat power to fight and win three simultaneous major conflicts, hard strategic choices were unavoidable. The American team quickly decided that losing Taiwan was not an existential threat to the United States, and except for a token Marine Corps force, Taiwan was left to fend for itself on the ground while substantial American air and naval assets challenged China’s access. The U.S. players viewed Taiwan as an economy of force effort that would be reinforced with ground troops once the big fight (Russia) was won. In the meantime, Team America opted to defend Taiwan with air and naval power, which continuously plagued Chinese attempts to reinforce their troops on the island. Similarly, South Korea, while viewed as crucial to long-term U.S. security, was also responsible for its own defense, although the American 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions arrived in force early-on, as did two regiments of American Marines. Still, the bulk of the fighting was left to South Korean forces.

Believing that China and North Korea had no military ambitions beyond their immediate objectives, the U.S. team adopted for a “Europe First” policy, similar to the strategic decisions the nation made during the Second World War. Consequently, eight American Army divisions, most of the Marine Corps, and significant air assets made their way to Europe. Interestingly, the U.S. team decided to send almost all of its naval assets to the Pacific, which made the GIUK gap vulnerable. The scenario allowed for a lengthy strategic build-up in Europe. But because the conflicts in the Pacific were more opportunist, they were mostly “come as you are” affairs.

What Happened When the Guns Started Firing?

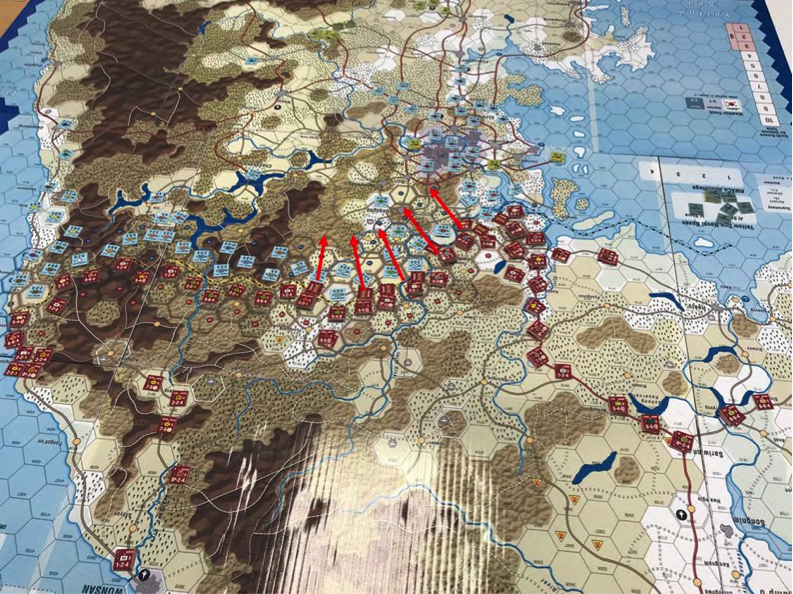

The South Koreans had time to alert their border forces and begin moving troops up from the southern part of the country. But the North Koreans struck before these reinforcements were fully deployed. The original North Korean intent (as shown in the picture below) was to strike hard, bypass Seoul, and drive deep into South Korea.

The North had some initial success in front of Seoul and managed to break through South Korean lines in the center. Fortunately, the North Koreans were unable to exploit this success before U.S. Marines and the Army’s 2nd and 25th Divisions, advancing from the south, built a second defensive line along the Bukhan River.

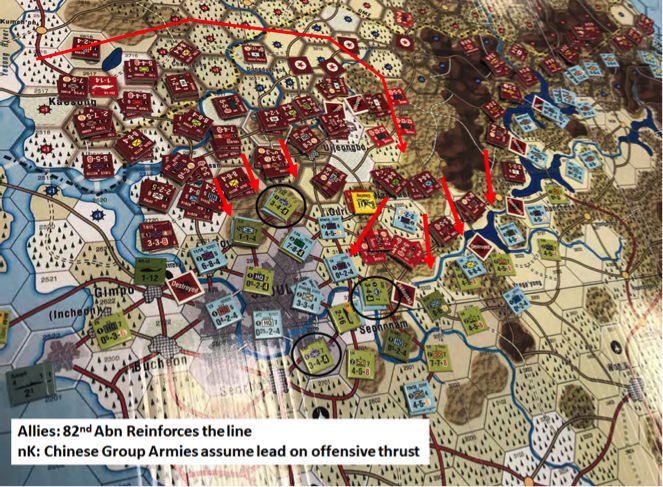

With the center offensive halted by American reinforcements, the North Koreans shifted the bulk of their assaults toward Seoul, which acted like a magnet upon any forces in the area. By now the North Koreans were behind schedule and congestion was slowing the build-up of North Korean combat power along the battle-line. To regain momentum, the Chinese committed their 79th and 80th Armies to the offensive (circled in red below). But with American forces supporting the South Koreans in front of Seoul and along the Bukhan River, the attack’s progress slowed. It is worth noting that much of the American success was due to huge amounts of sorties flown from bases in South Korea, Japan, and nearby carriers. However, when China entered the fight, the carriers were forced to pull back beyond DF-21 and DF-26 range.

With South Korea under extreme pressure, the U.S. team shifted the 82nd Airborne Division from its reserve position in Warsaw, Poland to Seoul. After redeploying to the other side of the globe, the 82nd was immediately injected into the fight. This proved enough to stymie the Chinese offensive, at least temporarily.

In an attempt to get things moving again, the North Koreans resorted to chemical weapons. With no adequate conventional response to chemical strikes, which inflicted tens of thousands of military and civilian casualties, the INDOPACOM commander requested nuclear release authority.

In Taiwan, after a brief but spirited defense of the nation’s beaches, Taiwanese troops were forced, by a successful Chinese airborne assault that captured a port in their rear, to retreat into the nation’s mountainous interior.

As the Chinese consolidated their beachheads, brought in heavier forces, and moved cautiously inland, the Taiwanese fell back on Taipei. Here they intended to launch local counter-attacks and hold at least a portion of the island until the United States came to their aid. The Chinese build-up was severely hampered by U.S. naval and air power, which, despite the retreat of the carriers, was able to inflict serious losses upon the Chinese invasion armada and damage their debarkation ports in Taiwan. On the ground, the resistance of the Taiwanese forces was stiffened by the insertion of Japanese forces into the line — a result of American investments in pre-war directed diplomacy and a Japan concerned that both Taiwan and the Republic of Korea might fall to China. The Chinese, unable to make headway in the rough terrain and suffering from numerous local counter-attacks, as well as drawn out clearing operations in urban areas, soon settled into static positions, while they awaited more combat power to arrive from the mainland.

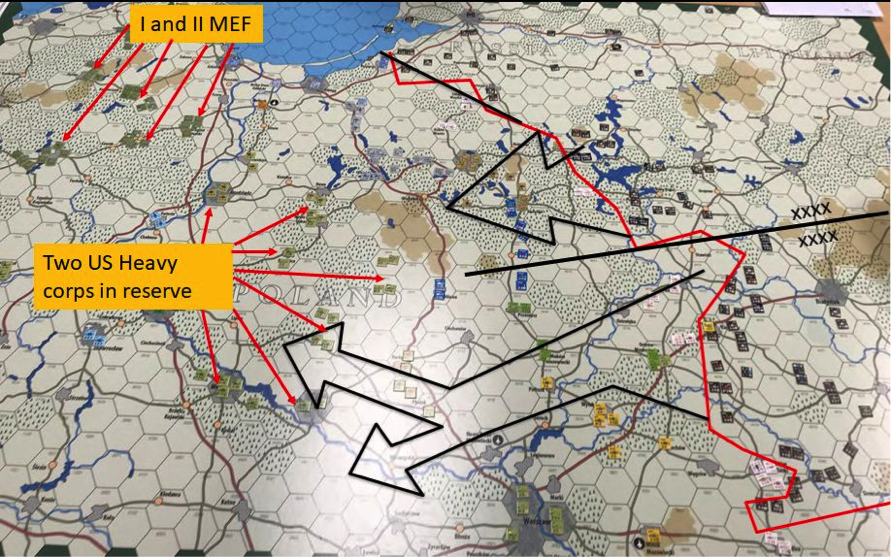

The fight in Poland was beyond brutal. By student estimates, the NATO forces lost over 60,000 men and women on the first day of the fight — shades of the Somme. The Poles, determined to hold as much of their national territory as possible, refused to fall back on the main NATO defense line and were severely handled. As the map below shows, U.S. Army divisions were initially set well back from the line as a counter-attacking force.

Despite the NATO commander’s best intent, it proved impossible to hold the American force together for one massive counter-strike. Due to unrelenting Russian pressure along the front, the American leadership was forced to disperse all its divisions to prop up wavering allies. Interestingly, this led to the third Battle of the Masurian Lakes or Tannenberg — the first being in 1410 and the second in 1914.

To stop the Russians, the NATO Commander was forced to employ 10th Mountain Division to prop up the battered Poles (white units on the map), while the 1st Cavalry and 1st Armored Divisions counter-attacked further south. The result was a bloodbath that left every Allied and Russia unit engaged gasping, with most suffering about 50 percent losses within a 72-hour period.

After days of hard fighting, NATO managed to stabilize its front, making it possible to pull several heavy divisions off the line and launch a devastating counter-attack on the Russian southern flank, while a marine expeditionary force trapped an entire Russian division in the north. At this point, intercepts of Russian communications indicated their commanders were asking for nuclear release.

Observations and Lessons Learned

The post-conflict after action review was informative and left the students with much to ponder. Before listing just a few of the lessons learned, it is important to note that they are the result of only two days of game play. Moreover, these games were designed to help the students think about future conflicts and operational art, and not for serious analytical work. Still, there were several observations that may point the services and Joint Staff toward areas that require more serious analysis.

The high rate of loss in modern conventional combat challenged student paradigms ingrained by nearly two decades of counter-insurgency operations. In just the first week of the war, U.S. forces and their allies suffered over 150,000 losses (World War I levels of attrition) from the fighting in Poland, Korea, and Taiwan. For students, who have spent their entire military lives viewing the loss of a squad or a platoon as a military catastrophe, this led to a lot of discussion about what it would take to lead and inspire a force that is burning through multiple brigades a day, as well as a lengthy discussion on how long such combat intensity could be sustained.

Because of these huge battlefield losses and how long it would take to get National Guard and Reserves into the fight, the decision was made to strip these forces of most of their trained personnel and use their troops as replacements for battered active units.

To ease the students into the complexity of this wargame, logistics was hugely simplified. Still, much of the post-game discussion focused on the impossibility of the U.S. military’s current infrastructure to support even half the forces in theater or to maintain the intensity of combat implied by the wargame as necessary to achieve victory.

Airpower, the few times it was available, was a decisive advantage on the battlefield. Unfortunately, the planes rarely showed up to assist the ground war, as they prioritized winning dominance of their own domain over any other task. Only when the Air Force had completed a multi-week campaign to take down the enemy’s Integrated Air Defense System( IADS) and win the air-battle, were they willing to assist the ground battle. In the Pacific, the unwillingness to risk carriers within the 900-mile range of Chinese DF-21s and 26s made them close to useless, unless they could operate under a land-based air defense umbrella.

Neither America nor its allies had any adequate response to the use of chemical weapons by the enemy, short of requesting nuclear release. It is worth noting that every battle headed rapidly toward total war, as both sides commanders sought to escape restraints on what weapons they could employ within a theater. Every time a theater commander met with a military setback they requested authority to employ nuclear weapons

Neither U.S. forces nor allied forces had an answer to counter the overpowering impact of huge enemy fire complexes, which accounted for most American and allied losses.

Cyber advantages always proved fleeting. Moreover, any cyberattack launched on its own was close to useless. On the other hand, targeted cyber attacks combined with maneuver forces always proved to be a deadly combination.

When NATO is all-in, it can put a huge effective force in the field. But it is important to remember that NATO was only all-in because the students took a huge amount of their investment budget and applied it to directed diplomacy, aimed at rebuilding frayed alliances. Still, the Russian occupation of Ukraine, the Baltics, and Belarus did a lot to focus the attention of NATO allies on the looming threat.

In Korea, the allies must hold for approximately 10 days before the North Korean logistics system collapses. It’s important to note, however, that the fighting remains brutal even after North Korea’s logistics system collapses. Moreover, the restrictive terrain and density of forces leads to particularly intense combat.

How Did We Play?

For those interested, the games used are all part of GMT’s Next War Series, designed by Mitchell Land and Greg Billingsley. I have found these commercial games are far more sophisticated and truer to what we expect future combat to look like than anything being used by most of the Department of Defense’s wargaming community which is often decades behind commercial game publishers when it comes to designing realistic games. In fact, if I was to fault the Next War series for anything, it is that it may be overly realistic and therefore very complex and difficult to master, and time consuming to play. Thankfully, the designer has agreed to produce a simplified rule-set that will allow for more student iterations without sacrificing realism.

The War College was also ably assisted by Col. Tim Barrick and Mark Gelston from the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab’s Wargaming Division, and by some folks from the local gaming community who were indispensable in helping with the mechanics of each game, allowing the students to focus on operational and strategic decision-making.

Thoughts on Wargaming in Professional Military Education

In 2016, I wrote an article on my employment of wargames as part of a larger program of historical teaching at the Marine Corps War College (MCWAR). In that article — which caused quite a stir according to my editor — I said that I hoped to expand MCWAR gaming to include examinations of future war. After some smaller experiments with portions of the class, this exercise represents my first major effort to involve all of the students in a complex global game. It came off far better than I expected, but there remains plenty of room for improvement. The major deficiency is due to it being a stand-alone event. Next year I hope to enhance student learning by making time for serious strategic discussions of options, as well as for extended planning, and turns dealing with the challenges of bringing Reserves and material across the Atlantic and Pacific in the face of a determined peer threat.

After every wargaming event I am bombarded with requests for a second and third iteration of the game, as students always want to try different approaches and strategies. Unfortunately, there is never time to do this. This is tolerable when I am using wargames to teach military history. But the job of any professional military education institution is to better prepare its students to successfully confront the challenges of a future conflict — make them better warfighters. As such, I plan on asking the school leadership for more class hours dedicated to student wargaming reps-and-sets to help develop the instant pattern perception that future conflicts will demand of them. I would argue that mental preparation for future conflicts is best accomplished through repetitive wargaming that allows students to explore operational and strategic options. This is, in fact, how we won World War II, but since then we have lost our way. It is well past time to reinvorgate forward-looking wargaming throughout all of professional military education.

In the three years since my original wargaming article, I have been asked to talk about employing wargames in the classroom at nearly every professional military education school, with the notable exception of those run by the Air Force. And, I can now report it has made no difference whatsoever! Oh yes, some schools have added a capstone type event with hundreds of participants. Unfortunately, such mass-events are useless as learning tools. Only in a few isolated pockets — Ben Jensen at Quantico, Corbin Williamson at Montgomery, and Nicholas Murray at Newport — are wargames being employed on a regular basis in the classroom. And, except for these same three professors, I am unaware of anyone who is allowing students to get multiple “reps-and-sets” to explore the challenges of future conflicts.

Interestingly, many of these schools have entire wargaming departments, divisions, or sections established to support classroom wargaming. Unfortunately, these wargaming groups, despite their strenuous efforts to assist in the classroom, spend most of their time designing games for the Office of the Secretary of Defense or higher senior level staffs. What they are failing to do is increase the amount of classroom wargaming, or experiential learning in their institutions. They do have two get-togethers every year (Connections Conferences) where they happily talk about how great wargaming is, and sometimes they even ask why no one else in their respective schools seems to think so. So for the next Connections get-together, in August at Carlisle, I would like to suggest a panel topic: Why are we failing?

There is, however, hope on the horizon, as drafts of the Secretary of Defense’s professional military education guidance appear to aim at making wargaming a core component of military education, and integrating war games throughout the curricula. The Pentagon staff also appears to want a large expansion of all types of experiential learning to better examine historical and contemporary decision-making to gain a better understanding of how strategy and operations have evolved over time. Presently these directed expansions of experiential learning techniques include increasing not only war gaming, but also the use of the historical case study method, and decision forcing exercise, all of which is aimed at supporting and enhancing critical thinking and operational/strategic analysis.

The chairman’s office appears to be leaning in the same direction. Current draft guidance calls for professional military education institutions to incorporate more “active and experiential learning methods” to help develop their students’ practical and thinking skills. Further, schools will be told to establish curricula that leverages wargames and exercises that allow students multiple sets and repetitions on realistic operational and strategic problems. To make room for these experiential strategy and warfighting programs, the leadership of various school is being encouraged to “ruthlessly reduce coverage of less critical topics.”

This renewed focus on wargaming goes hand-in-hand with demands to greatly increase the amount of military history taught in professional military education, which is found in both sets of guidance. Of course, neither will happen unless these directives are relentlessly and ruthlessly enforced by senior leaders. For example, it has now been nearly eighteen months since the National Defense Strategy stated that professional military education has stagnated, and demanded more history instruction, as well as directed a move to a ‘great powers’ intellectual paradigm. Since then, virtually no changes have been made to professional military education curriculums to meet this guidance, although the Navy’s Education for Sea Power Initiative might break the logjam.

To insure change takes place, the Program for Accreditation of Joint Education inspection teams must start every accreditation visit by demanding “proof” that professional military education institutions have expanded their military history offerings and wargaming programs. If inspection teams do not demand it at every visit, it will not happen.

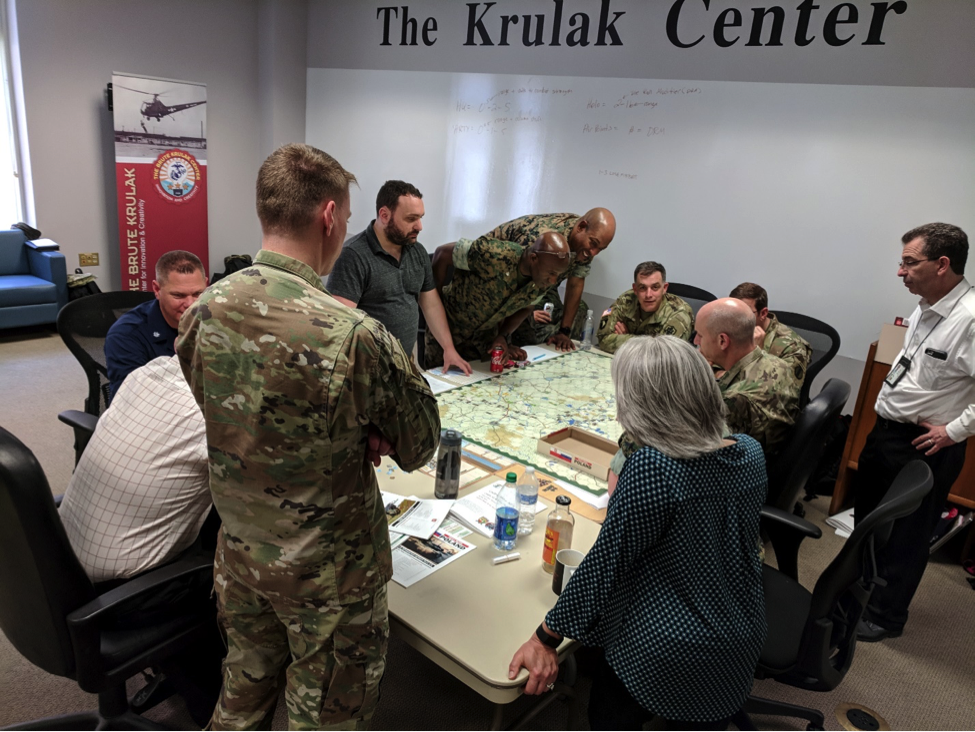

One would think that professional military education schools would do this on their own, but when it comes to teaching activities that are never forgotten and continuing to influence student-thinking for decades, nothing compares to wargaming and other types of experiential learning (such as staff rides). Where else do you get the kind of buy-in and prolonged student involvement seen in the pictures inserted throughout this article? Wargaming works. It is time to force it down the throats of faculties too hidebound to change on their own.

Dr. James Lacey is the Professor of Strategic Studies at the Marine Corps War College. He is the author of Great Strategic Rivalries and the forthcoming The Washington War. This article reflects the opinions of the author and in no way reflects the opinions of Marine Corps University, The U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense or any of its related organizations.