When Can a Soldier Disobey an Order?

In March 1968, a U.S. infantry platoon under the command of 2nd Lt. William “Rusty” Calley conducted a raid of a hamlet called My Lai in Quang Ngai Province of South Vietnam. After taking the hamlet, Calley ordered his men to round up the remaining civilians, herd them into a ditch, and gun them down. Somewhere between 350 and 500 civilians were killed on Calley’s instruction.

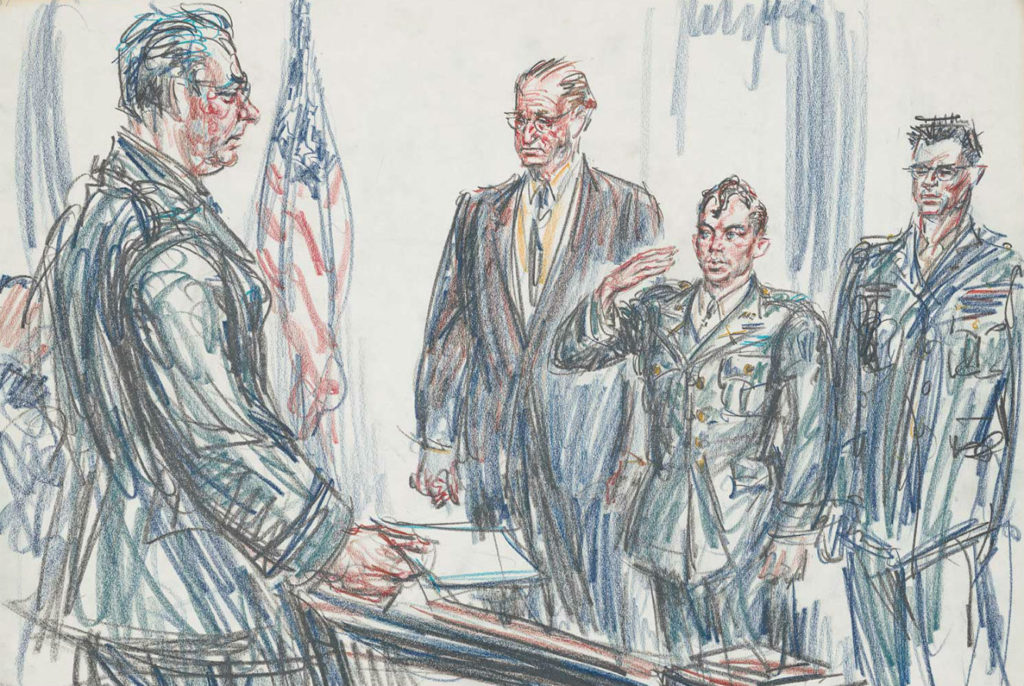

Calley was court-martialed for his actions and charged with 22 counts of murder. At his trial, he testified that his company commander, Capt. Ernest Medina, had ordered him to kill “every living thing” in My Lai, telling him there were no civilians there, only Viet Cong. When Calley radioed back to Medina that the platoon had rounded up a large number of unarmed civilians, he claimed Medina told him to “waste them.” Essentially, Calley defended gunning down hundreds of civilians by saying he was just following orders from his superiors (It should be noted that Medina denied giving these orders).

But Calley was unable to hide behind this defense. Every military officer swears an oath upon commissioning. That oath is not to obey all orders. It is to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” It is simply wrong to say Calley had an obligation to follow any order no matter what. His first obligation was to obey the law, and the law prohibits the deliberate killing of unarmed civilians.

But it’s not enough to assert that soldiers must follow all lawful orders and disobey unlawful ones. Not every case is clear-cut. Soldiers taking orders in combat must act quickly and don’t always have time to calmly deliberate on every decision. Asking soldiers to make fine legal distinctions in combat or else face court-martial is akin to asking them to sail between Scylla and Charybdis.

This tension is resolved by rules contained in the Manual for Courts Martial. The manual is an executive order that augments the Uniform Code of Military Justice by setting forth procedural rules and providing guidance based on case law for interpreting the code. Rule 916(d) of the Manual for Courts Martial says:

It is a defense to any offense that the accused was acting pursuant to orders unless the accused knew the orders to be unlawful or a person of ordinary sense and understanding would have known the orders to be unlawful.

Calley was convicted under this rule. The court found that “whether Calley was the most ignorant person in the United States Army in Vietnam or the most intelligent,” he would have to have known that it was illegal to slaughter civilians who were “demonstrably unable to defend themselves” and that the order was “palpably illegal.” The court noted that, “For 100 years, it has been a settled rule of American law that even in war the summary killing of an enemy who has submitted … is murder.”

So the order Calley tried to use as a shield against criminal liability – the order to slaughter civilians – was so clearly illegal that any reasonable person would have known it was illegal. But what other, less clear-cut orders might give rise to an obligation to disobey?

It is obvious that a soldier could not refuse to disobey an order simply because he disagreed with its tactical wisdom. An order to advance along one route rather than another is obviously legal, even if the subordinate thinks it is a bad idea. What if, however, if a soldier’s objection is raised sooner, well before he reaches the battlefield, and what if that objection is rooted in a debate about the powers of the presidency? Can a soldier refuse an order to deploy in support of a military operation that Congress has not approved?

The president’s authority to use military force is a hotly debated legal topic. In recent years, presidents have used force against al-Qaeda and associated groups, and more recently against ISIL, in places as far-flung as Yemen, Somalia, Iraq, and Syria. These presidents relied for their authority on the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force, a reading that stretches the meaning of the authorization to its logical limits, and arguably well beyond. In 2011, President Barack Obama went even further, launching a major military action in Libya without making any effort to get congressional approval or attempting to cite the Authorization for the Use of Military Force. Instead, he relied on a U.N. Security Council vote to create a no-fly zone as legal authorization for what became a forcible change of Libya’s regime. At any rate, the fact that the president’s war-making powers are hotly debated is why it would be virtually impossible for a servicemember to refuse to deploy because he believed the war was improperly commenced. When both sides have a plausible argument in their favor, the order is not “palpably illegal.”

A few servicemembers have tried unsuccessfully to disobey orders to deploy in support of these operations. In 2006, 1st Lt. Ehren Watanda refused to deploy to Iraq because he believed the war was illegal. His arguments fell on unsympathetic ears. In fact, Watanda was not even permitted to present his preferred defense because

[t]he order to deploy soldiers is a non-justiciable political question … an accused may not excuse his disobedience of an order to proceed to foreign duty on the ground that our presence there does not conform to his notions of legality.

Courts are not empowered to second-guess policy decisions made by the political branches. In the end, Watanda was administratively discharged under other than honorable conditions for his refusal to deploy.

In 2016, Capt. Nathan Michael Smith deployed to Kuwait to support the fight against ISIL, but he also filed a lawsuit in federal district court challenging the legality of the order. The suit was rejected for the same reason Watanda’s defense failed: The judge ruled that the decision to wage war was reserved for the political branches. The fundamental problem in both the Watanda and Smith cases was that the order to deploy was not palpably illegal.

As My Lai shows, however, there are cases where an order would clearly violate the law. An order to torture a detainee would be one. Every soldier is trained to know that torture is illegal. The U.N. Convention Against Torture, to which the United States is a party, prohibits cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment of detainees. Army Field Manual 2-22.3, which governs human intelligence collection, also bans torture. It permits 19 types of interrogation techniques, none of which could be considered torture, and two of which require special authorization to use. Under the McCain amendment to the 2006 National Defense Authorization Act, no Department of Defense employee may use any interrogation technique not authorized under the Army Field Manual. Torture is also explicitly prohibited by DoD Directive 3115.09.

It would be palpably illegal to give an order to torture a prisoner. There is no defensible legal argument that interrogation techniques such as waterboarding are permitted. No soldier, sailor, or airman would be in a position to plead ignorance of the law. Any member of the military who received such an order would not just be allowed to disobey it – they would be required to do so. Otherwise, they would face the threat of criminal charges under Article 92 of the UCMJ, for dereliction of duty in failing to follow lawful regulations and for cruelty and maltreatment, and Article 134, for general misconduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline. The officer would also be at risk of being charged for conduct unbecoming under Article 133.

This is exactly what happened after the conditions at Abu Ghraib prison were made public in 2004. The lurid details of widespread abuse of prisoners, including sexual abuse and humiliation, are by now well-known. Eleven soldiers were found guilty of various charges at court-martial for their involvement in prisoner abuse. Two senior officers who had overseen the prison, Lt. Col. Steven Jordan and Col. Thomas Pappas, also faced disciplinary action for their dereliction in supervising the facility.

Some of the soldiers involved in the abuse tried to assert superior orders as a defense, though none were successful. It was true that Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, the commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, had authorized the use of dogs, sleep deprivation, and extreme temperature exposure as interrogation techniques. None of these were permitted by the Army Field Manual in place at the time, FM 34-52. They should not have been authorized and Sanchez’s memo was an illegal order, though he ultimately faced no disciplinary action for it. Because the soldiers involved in the scandal were assigned to detainee operations, they would have been expected to know what techniques were and were not authorized by the manual. The only way they could defend themselves from the charge of dereliction in knowingly failing to follow the rules would be to admit they committed the crime of dereliction by not bothering to learn the rules.

Further, most of what went on at Abu Ghraib went far beyond anything authorized in any memo or order. Guards urinated on detainees, forced them to simulate oral sex on each other, forced them to remove their clothes and lie naked in piles together, and sodomized them with broomsticks. There were even instances of U.S. soldiers raping female inmates. None of this was authorized at any level, nor could it have been authorized. Any soldier who was ordered to do any of this should have immediately understood that the order was illegal and would have been obligated to disobey and report the abuse.

This same rule would apply in the case of any clear law-of-war violation. In combat, commanders must make difficult decisions to launch strikes that risk civilian casualties. The law of war does not require that commanders avoid any risk of civilian casualties, but it does mandate that strikes meet the tests of necessity and proportionality, meaning the value of destroying the target outweighs the risk of civilian casualties. When a commander makes a judgment call that destroying a particular target is worth the risk of collateral damage and his judgment is reasonable, his subordinates have to carry out the order, although they themselves might have made a different judgment.

Still, certain strikes might be palpably illegal. The Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits a wide array of attacks against protected persons. For example, attacks targeting civilians are explicitly prohibited under Article 27. So are attacks on hospitals, pursuant to Article 18. Reprisal attacks are also barred under Article 33, so if a commander orders his soldiers to harm the relatives of a terrorist or to destroy their property in retaliation for attacks on U.S. troops, that would be clearly illegal. His subordinates would be required to disobey the order. Recall that My Lai was a reprisal attack: Members of the unit later said the motivation was revenge for the recent killing of a popular sergeant by enemy forces.

The defense of superior orders in cases of reprisal attacks is so weak that it is hardly ever attempted. In the spring of 2008, soldiers of Alpha Co, 1-18th Infantry lined four Iraqi prisoners up near a canal and executed them. The Iraqis were captured during a raid of a house found to contain weapons. They denied knowing anything about where the weapons came from, which was almost certainly a lie. The company’s first sergeant ordered that the Iraqis be transported to a nearby canal, where he instructed his men to shoot them, saying it was revenge for fallen comrades. Some of the men in the unit balked and refused, but others participated in the killings. When the incident was finally exposed, those involved in the killings were tried by court-martial. One soldier simply pleaded guilty. Another fought the charges, but did not attempt to defend himself by saying he was under orders. Rather, he said he was under so much stress because of combat that he could not be held accountable. That soldier was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. The first sergeant who gave the order denied the killings had happened at all. He, too, was convicted. No one involved pretended that the first sergeant’s order excused their conduct because that defense had no realistic chance of success.

The military is a hierarchical organization. Some degree of obedience to the orders of superior officers is required for the organization to function. But those who serve in the U.S. military are not automatons, and they are not asked to surrender all independent moral judgment when they sign their enlistment papers. American servicemembers are defending a nation of laws, not of men. Their obligation to obey the orders of their superiors does not include orders that are palpably illegal.

John Ford is a former military prosecutor and a current reserve U.S. Army Judge Advocate. He now practices law in California. You can follow him on twitter at @johndouglasford.