Building An Open-Source Intelligence Buyer’s Club

The Ukraine conflict has blown open the door on how open-source information — broadly defined as publicly and commercially available data — can be a game-changer in war and peace. The broad array of unclassified tools now allows anyone to pore over satellite imagery, monitor tank convoys, listen to troops chatting over unsecured communication devices, watch ship movements, and determine the location of Russian oligarch-owned superyachts. Governments are still trying to catch up with the amount of data flowing in all directions across hundreds of platforms, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Despite the current glossy appeal of open source, both democratic and authoritarian governments alike have struggled to collect, make sense of, and then provide relevant information to their end-users. Those in U.S. national security circles yearn for a technical solution — a database to sort and categorize this vast amount of data. The tech challenges are certainly complex, and the problems with data integrity and validation remain vexing and require real solutions to categorizing, verifying, and then sharing this information.

But the United States’ decades-long romance with technological fixes to complex national security problems takes the wrong perspective. The government’s challenge with open source isn’t just a technical one; it’s a political science one. And once Washington asks the right questions, it can begin to solve the collective action problem that lies at the heart of the open-source intelligence question.

Yet to achieve progress, then an able leader must both exploit a crisis and then muscle it through a bureaucratic, often-political system resistant to change. But there might be a better way: government agencies and departments could work with America’s colleges and universities to devise a “buyers club” of open-source tools and databases, which government agencies can collectively purchase from a decentralized or a loosely centralized database. The best part: several Washington DC-area university libraries have already figured out how to collect vast amounts of public information, make it easily searchable, and provide assistance when needed, yet allow every university library to maintain its own holdings and identity. It’s a win-win for academics, and it could be a win-win for the government as well.

Old Wine in New Bottles

Exploiting open sources to craft intelligence is nothing new. President Richard Nixon famously told Director of Central Intelligence James Schlesinger what he thought CIA’s employees were doing all day: “Get rid of the clowns. What use are they? They’ve got 40,000 people over there reading newspapers.” (Schlesinger then cut ten percent of the CIA’s workforce during his 17-week tenure.)

Two decades later, in 1992, Deputy Director of Central Intelligence William Studeman said over 80 percent of CIA analyses came from open sources — although it’s unclear if he was referencing an actual analysis of CIA sources or a back-of-the-envelope guess. A few years later, in 1996, before the term “social media” was even coined, the Congressionally-commissioned Aspin-Brown Commission found, “open sources do provide a substantial share of the information used in intelligence analysis…with more and more information becoming available by electronic means, its use in intelligence analysis can only grow.”

Longtime editor of Intelligence and National Security Loch Johnson argued in Foreign Policy in 2000 that some “90 to 95 percent” of information contained within finished intelligence came from public sources; in 2007, Director of National Intelligence Michael McConnell held an Open Source Conference where he noted some 600,000 terabytes of “open source” data moved through the Internet every day (for context, the Library of Congress makes up about 100 terabytes of data). The challenge was to make sense of it all. Even now, in 2022, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) is formulating a new open source intelligence plan for the future to do just that and to grapple with the vast amounts of data available for government analysts to use.

America Has the Money, But Not the Strategy

Open-source efforts nowadays are a frustrating “collection of cottage industries,” as my Applied Research Lab for Intelligence & Security colleagues former National Intelligence Chair Neil Wiley and Defense Intelligence Agency Director Robert Ashley wrote in mid-2021. The whole system is hobbled by the fact that open-source government analysts must bootstrap their way into using it, noting, “The conspicuous absence of common standards, community coordination, and enterprise governance make [open source] more difficult to use in all-source assessment than classified information produced by the [intelligence community’s] more established disciplines.”

Washington certainly spends significant tax dollars purchasing data, databases, and various technology platforms to meet its needs. But the government has long realized that much of its expensive work is duplicative. Even now, the U.S. government still appears to have only a dim idea of what open-source tools and databases it is using, buying, or supporting. Based on anecdotal conversations I’ve had over the last several months, the Department of Defense has the same problems that its Inspector General identified almost half a decade ago: namely, various parts of the Pentagon appear to still purchase identical, or similar, open-source databases despite working for the same organization. Across the nation, federal entities continue to struggle to communicate clearly with state and local authorities, while these organizations don’t share information or licenses with each other.

Complicating issues are age-old issues of turf and bureaucratic control. Resources controlled by one organization sometimes just become unavailable to others by unilateral decision. Perhaps the most well-known was when the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) — the U.S. government institution that collected, translated, and disseminated news stories from across the world since the 1940s — became unavailable to the public. Researchers outside the government who then informed the government and policymakers lost a vital resource that helped with analysis and writing.

The reason: the CIA — which sponsored the service — simply cut off access in 2014. The Agency claimed at the time, somewhat unbelievably, that it was “cost prohibitive” to maintain the service and that other publicly available information was now readily available on the internet. This was despite, as one FBIS Deputy Director noted in the 1990s, the fact that the intelligence and policy communities valued the work of private scholars who “contribute[d] significantly to the national debate on contemporary issues.” There’s also a conscious or subconscious view that classified information is superior to unclassified material simply because it was difficult, expensive, dangerous, or all three to generate it. As such, fewer people have access to them, giving those with access the perception that the information they possess must be “better” than open-source information.

Finally, this challenge is further compounded by a smothering fog of various rules, guidelines, regulations, classifications, funding mechanisms, and of course, the peculiarities of individual entities and personalities. Thus, these variables would perplex the most stalwart supporters of government efficiency.

Leadership in a Crisis Still Makes a Difference

It’s not as if overwhelming bureaucratic inertia and changing fundamental mindsets are new concepts in the national security space; the United States has seen this dynamic play out repeatedly over the last several decades. Here are three examples of how progress came about via crisis and effective political leadership:

The Defense Intelligence Agency was founded in 1961 because the Eisenhower Administration wanted to centralize the Pentagon’s unwieldy intelligence efforts. But this agency was also born from the late 1950s “missile gap” crisis, amidst sharp Congressional critiques and conflicting military service estimates of the Soviet missile arsenal. After John F. Kennedy was elected, his new Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara then midwifed this new organization over the bitter feelings among military officers.

Over forty years later, two major bureaucracies emerged from the ashes of 9/11: the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. While there had been previous efforts to centralize intelligence work — the “Central Intelligence Agency” was one such effort — the Director of National Intelligence is now the titular head of the U.S. intelligence community, while the Director of Homeland Security is responsible for issues related to natural and man-made disasters inside the U.S.

Homeland Security’s creation was a herculean effort to merge 22 federal departments in the shadow of 9/11 and the desire for the White House to thwart Senator Joe Lieberman’s proposed legislation for a vast new homeland bureaucracy following the 2001 attacks. At the time, the Bush White House was lukewarm on his idea, but then developed a plan, mostly in secret, and muscled it through without informing many department heads until the new organization’s design had been solidified. The corresponding legislation was then jammed through Congress as a White House priority over the objections of some senior Senate Republicans; as Sen. Fred Thompson told Lieberman, “I’ve been having a great time explaining my enthusiastic support for a proposition I voted against two weeks ago.” The Homeland Security Act became law in November 2002.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence had a more thoughtful trajectory toward creation since it stemmed from the 9/11 Commission’s recognition that sharing intelligence across different entities might have stopped the 2001 attacks. Like Homeland Security, overhauling the intelligence community was a Bush Administration priority, but it faced pushback from many who viewed the proposed organization as a new layer of intelligence bureaucracy. Former national security advisor Brent Scowcroft was further concerned with “moving the boxes” during several global conflicts.

While the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act passed 96 to 2 in the Senate, it faced far rougher waters in the House, losing 67 Republicans and 8 Democrats in the final vote. The Director of National Intelligence concept could have died but for the crisis of 9/11 and aggressive efforts by the Administration and its allies to push the unwieldy, complicated legislation through Congress. Of course, had a devastating follow-on terrorist attack occurred in the years following the organization’s founding, a further radical ‘reformation’ of America’s national security bureaucracy would have likely been in the cards.

America’s Heroes: Librarians

RAND in 2022 and Harvard’s Belfer Center in 2020 both argued for a stand-alone open-source entity that would collect and disseminate unclassified open-source information. But inertia is a powerful force, bureaucratic inertia doubly so.

Whatever its merits, establishing yet another government organization — an open-source center to rule them all — will require an enormous investment of the White House’s political capital to move comprehensive legislation through a politically-polarized process where less than ten percent of bills become law. Each agency will inevitably maintain its own indigenous capability to meet its own needs, creating some redundancies. That is normal.

But one way to solve the government’s open source collective action problem without upsetting any bureaucratic fiefdom would be to develop a loose university “consortium” or “buyers club” model. This would create more efficient, more productive, and cheaper outcomes for the U.S. government than trying to build vast, duplicative, expensive open-source organizations within existing agencies.

A consortium could maintain all the open-source materials, databases, and platforms for the national security apparatus. It could ingest other open-source data from other parts of the government — census data, agricultural yields, labor statistics, etc. It could even collect open-source information from other countries’ governments and nongovernmental organizations. What the national security agencies then do with this information is up to them.

Hosting open-source capabilities at a large institution outside of the government such as a large university would sidestep much of the occasionally sclerotic government processes. A network of universities could further serve as the information and technology backbone of this open-source consortium, as well as tap into a deep well of individuals affiliated with them to bring perhaps radically different perspectives to the government.

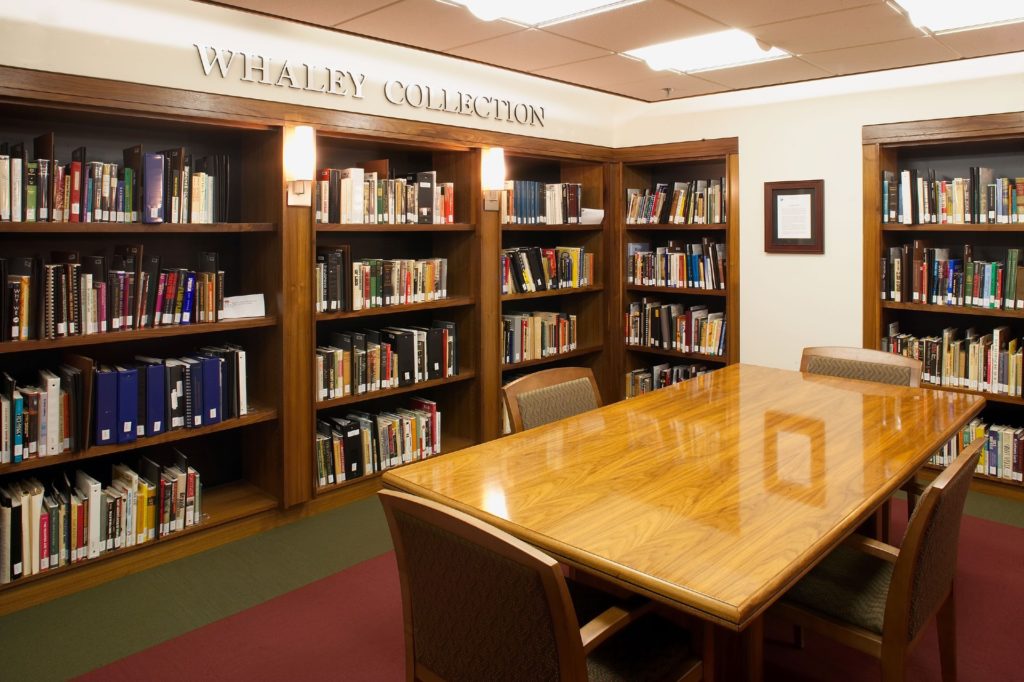

The government doesn’t even need a crisis to make this happen. There’s at least one crisis-less example of solving this problem, involving some of America’s unsung heroes: university librarians. In the 1980s, several universities in the Washington DC area realized the advantages of pooling collections and sharing discounted rates on electronic resources. Capitalizing upon a 1960s-era interlibrary loan system, in 1987 these universities founded the Washington Research Library Consortium. It’s now a virtual library across the region, with over 5 million shared volumes. As the Consortium’s Executive Director Mark Jacobs noted in an interview with me, this arrangement allows its libraries to move its physical collections into a shared facility, “which is much less expensive storage than an on-campus library.”

Beyond cost savings, these universities mitigated many of the collective action problems by structuring the Consortium in such a way that each library maintains its own catalogs to meet the needs of its host institution — its “identity.” As American University librarian Melissa Becher noted, “It has been a situation where we cooperate on things that we can agree on and which are advantageous to everyone while remaining quite separate libraries whose individual interests do not suffer too much from the arrangement.” Everyone has an incentive to work together. In other words, the benefits of cooperation far outweigh the costs.

It’s devilishly hard to solve technical problems, and the government should help fund and solve those thorny challenges. However, it is perhaps even more difficult to solve collective action problems because there is often no clear path against entrenched interests. The government can certainly continue down the fragmented path, as it has done for decades. However, just because we have followed this road doesn’t mean we have to stay on it for the foreseeable future.

Aki Peritz is an Associate Research Scientist at the University of Maryland’s Applied Research Lab for Intelligence and Security (ARLIS). He is the author of “Disruption: Inside the Largest Counterterrorism Investigation in History.” His bylines can be found in the New York Times, Washington Post, Politico, The Atlantic, and Rolling Stone.

Image: Wikimedia Commons