The Faultline Between Futurists and Traditionalists in National Security

It’s been boom times for national security and technology futurists. The dozens of articles on AI in War on the Rocks over the past few years are the tip of the iceberg. In the book market, P.W. Singer and his co-authors have published numerous titles on national security and modern technologies: robotics, cybersecurity, social media, and AI. Georgetown University’s new national security research institute, the Center for Security and Emerging Technology, not only honored the times with its apt name but also placed AI at the top of its research agenda. Researcher Elsa Kania’s writings (see her reports on the “Battlefield Singularity” or “Quantum Hegemony?”) have also helped to make the futurist discourse prominent, to give one example. Most importantly, the leaders and thinkers of this futurist camp have built a consensus that victory in great-power competition, especially between China and the United States, depends upon technological dominance and the mastery of emerging technologies.

National security and technology traditionalists, on the other hand, believe that the futurists misunderstand the purpose and sources of American power. In their view, the fundamental goals of American power relate to security, prosperity, and politics, and technological dominance is simply one means to these ends. Furthermore, traditionalists hold that the implications of emerging technologies have been overstated and that these nascent capabilities should be only one part of a broader national security and technology portfolio. For instance, a reader influenced by Stephen Biddle’s research on the relationship between technology and military power would have to strain to believe that that AI will “transform the way America’s military safeguards our nations.”

Both sides can agree on at least this though: This disagreement is not an intellectual exercise. It is better thought of as an intellectual faultline across which the push and pull of the tectonic debate will guide the attention and future decisions of senior leaders in the military, intelligence, and homeland security agencies. Leaders and their advisers will need to navigate the claims and counterclaims of these camps, and this piece is meant to serve as a high-level map — but not a compass — for these parties. This article explains each camp’s claims and perspective, and suggests broad methods for leaders to find balance and avoid an exclusive focus on either worldview. Without a map of this kind, senior leaders and analysts will govern over an unproductive debate between futurists and traditionalists in which scarce dollars are spent without the benefits of civil discourse.

The Futurists

Based on their reading of the technological trends, futurists worry that America is at risk of losing the emerging great-power competition with China, which they assert is based on technological advantage, itself underpinned by emerging technology. Technological dominance, argue the futurists, will ensure America’s ability to achieve all, or at least many, other strategic goals.

Great-Power Competition 2.0

A recent Council on Foreign Relations task force on “Innovation and National Security” enjoins the United States to “once again make technological preeminence a national goal.” The task force’s report contends that if America succeeds in accomplishing that goal, “the United States will continue to enjoy economic, strategic, and military advantages over potential rivals and would-be challengers.” A recent Center for New American Security report also channels the futurists when it argues that the United States “will steadily lose ground in the contest with China to ascend the commanding technological heights of the 21st century” unless it nurtures an “alliance innovation base.” Thinkers in this camp tend to de-emphasize war and conflict and instead see nontraditional threats from new technologies — misinformation fueled by Chinese and Russian bots or intelligence advantage gained by Chinese 5G networks — and technology-enabled opportunities.

Emerging Technology

Futurists frequently advocate for investment in a fourth industrial revolution that includes AI, robotics, quantum computing, 5G networks, 3D printing, virtual reality, synthetic biology, and other technological domains. Thinkers like T.X. Hammes and P.W. Singer have come to define this emphasis on emerging technologies. Futurists often believe that innovation in the modern era arises from commercial firms competing in a consumer market, not from yesteryear’s capital-intensive, military-focused industrial titans. Should the United States not invest in these technologies (a dangerous possibility because of organizational inertia), it could find itself losing the global race to technological superiority.

Prediction Based on Technological Writings

Futurists often cite technological writings drawn from scientific and business literatures. A reader is likely to find references to arXiv, an online repository for scientific articles, and to magazines and news sites such as Wired, Science, and Ars Technica. This choice of sources reflects a worldview that emphasizes the rapidity of technological change, the belief in the possibility of “revolutionary” technology, and the potential for “discontinuities” — that is, massive, non-linear shifts. These strategists therefore tend to rely on disciplined forecasts and prediction based on technological trends. Of note, some in this camp also champion science fiction as a vehicle for anticipating and preparing for the future.

The Traditionalists

Traditionalists view the futurists as zombie banner carriers for a mix of 1990s Revolution in Military Affairs thinking and the technological utopianism of Silicon Valley. These thinkers believe that the traditional goals of international politics endure, that the transformative aspects of emerging technologies have been overstated, and that the work of historians and social scientists makes these facts clear.

International Politics 1.0

To traditionalists, the trinity of security, prosperity, and freedom — not technological dominance — continue to be essential goals of American statecraft. In contrast to the futurists, the traditionalists also believe that war (or, more precisely, the threat or employment of military force) is still central to international politics. Leaders still want to achieve deterrence — preventing adversaries from challenging the status quo — or effect tangible battlefield outcomes such as taking and holding territory or killing or capturing a human enemy. Of course, interstate war has become an increasingly rare event, but American military preponderance, as noted by past RAND research, may itself be the cause of this decrease in conventional war. A traditionalist might also argue that preparing for war, including nuclear war, is the best way to keep war at bay.

The Limits of Emerging Technology

The traditionalists argue that the utility of emerging technologies for international competition and their importance to military superiority have been exaggerated. In this vein, Michael Mazaar and his RAND colleagues assessed recent Russian and Chinese information warfare activities and found “little conclusive evidence about the actual impact of hostile social manipulation to date.” This finding should surprise those strategists who believe that the internet and social media have transformed international politics and created an age of virulent state-sponsored disinformation. Academics Nadiya Kostyuk and Yuri Zhukov similarly find that cyber weapons — perhaps the emerging technology par excellence — have had a surprisingly small effect on battlefield events in Ukraine and Syria. A recent article by political scientist Jon Lindsay even takes aim at the supposedly revolutionary implications of quantum computers for signals intelligence and argues that the effect will be less than decisive given the organizational difficulties of implementing robust cryptosystems. Instead, writers such as David Ochmanek and Elbridge Colby and Stephen Biddle emphasize more traditional military technologies and rigorous training in the modern system of war, respectively, as keys to American military advantage.

Understanding Based on History

This different worldview has its origins in a disagreement over the best way to understand the future. Traditionalists look to the past, employing the tools of a historian or a social scientist. It’s no coincidence that the sources in this section tend towards the empirically rich study of the past with a focus on politics and organizations. Furthermore, skeptics avoid information sources such as Wired or Ars Technica that fixate on the latest gadgets and gizmos, preferring instead to wait for when these widgets have been put to the test of battle.

Navigating the Futurist-Traditionalist Faultline

First, senior national security leaders making technology-related decisions ought to ask questions that force futurists and traditionalists to confront their conflicting assumptions. Is achieving technological supremacy essential or even sufficient for achieving other important foreign policy goals? What is the contribution of emerging technologies versus traditional technologies for achieving broad geostrategic goals? What methods and evidence should the two sides of the debate use?

Otherwise, national security and technology thinkers will simply strawman or ignore each other. For instance, one recent writer, who might be placed in loose agreement with some of the traditionalist arguments, claims that Project Maven, a Pentagon AI initiative, aims to “take the guesswork out of the future by sucking in every email, camera feed, broadcast signal, data transmission — everything from everywhere — to know what the world is doing, with the omniscience of a god.” He labels the effort “hubris.” Our own reading of public coverage suggests that Project Maven actually intends to apply computer vision to overhead imagery. To us, this is a clear example of traditionalist thinking gone too far — his criticism, if taken seriously, would damn a range of current security-related AI experiments.

Second, leaders should acquire information — not in the sense of buying large datasets, but in terms of the “full exploration of new technology,” as described by Tom McNaugher’s Top Gun-era classic “New Weapons, Old Politics.” In other words, leaders should not drown out the disagreement but should let the two sides engage in high-stakes debate: There should be technology pilots, exploratory research, experiments, and wargames to better understand the opportunities, limits, and risks of new technologies. Towards that end, the national security establishment needs technology feedback channels to complement the growing number of acquisition channels. The Joint Artificial Intelligence Center’s recent open job postings for machine learning test and evaluation engineers indicates that it agrees.

Third, researchers ought to create methodological tools that will generate scientific evidence that both sides will find compelling. For instance, one promising avenue includes “synthetic history” research methodologies. These are methods that simulate military and foreign policy decision-making environments and use human actors, not models, as decision-making agents. For instance, Erik Lin-Greenberg employs wargames to study the effect of using unmanned technologies on crisis escalation, finding that the use of unmanned aircraft might actually lead to less escalation during future crises. One of us has done past research that uses a scenario-based survey of foreign policy elites to study nuclear weapons and conventional escalation in a hypothetical war between the United States and China. Futurists can use synthetic history to study untried technologies and traditionalists can appreciate the systematic evidence such methods create.

Fourth, schools of public policy or international relations and engineering programs will need to move onto each other’s turf to train a generation of “public-interest technologists.” This idea, popularized in part by cryptographer and information security thinker Bruce Schneier, is not just more software engineers working for the government, though that would likely be beneficial. Schneier defines public-interest technologists as “people who combine their technological expertise with a public-interest focus.” It’s a call to revamp education by training a cadre of civic-minded persons with hands-on technical experience, a broad understanding of technology, a commitment to asking and answering questions of societal importance, and a keen appreciation for the institutions of modern government. Some schools have already embraced this trend. It’s public-interest technologists who can help future leaders navigate this divide.

This faultline between traditionalists and futurists, which is often obscured from view, deserves more focused attention and further debate. Imagine a future episode of Intelligence Squared, the popular debate series, in which participants discuss this motion: “Emerging technologies are the key to 21st century power.” Eric Schmidt — former executive chairman of Alphabet, current chairman of the Department of Defense Innovation Board, and outspoken advocate of innovation in the Defense Department — or other commissioners on the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence could publicly debate this topic with futurists and traditionalists alike. The aftershocks of such a debate might be felt for many years to come.

John Speed Meyers holds a Ph.D. in policy analysis from the Pardee RAND Graduate School at which he wrote a traditionalist-leaning dissertation on U.S. military strategy towards China. David Jackson served as an officer in the United States Marine Corps and is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Their opinions are theirs and theirs alone.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technologies. In fact, it is the Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

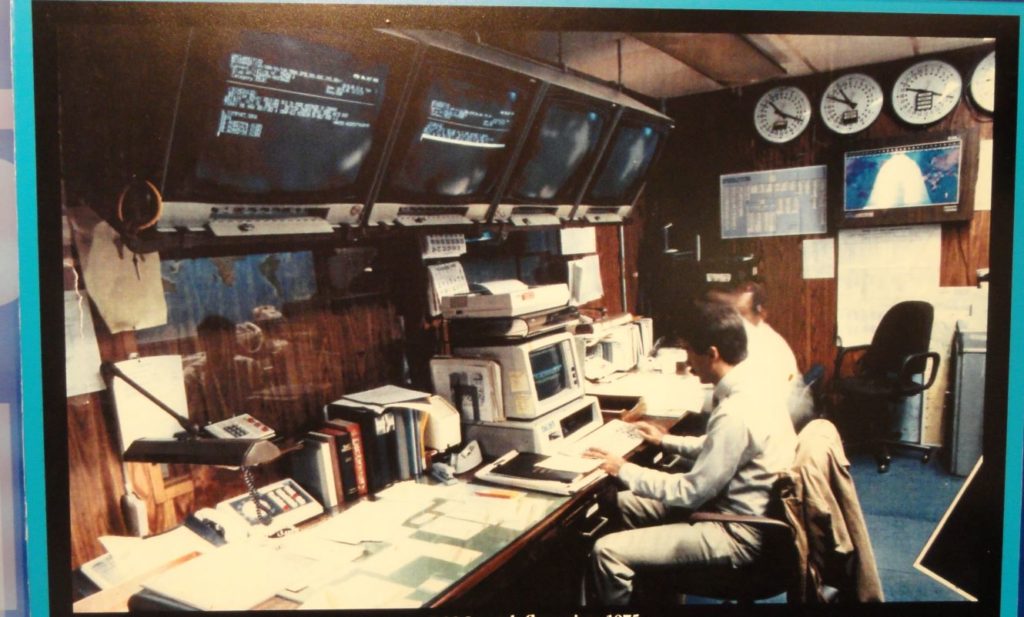

Image: U.S. government photo