The Abiding Relevance of ‘Heart of Darkness’ for Those Who Wage War

Joseph Conrad had a long career as a merchant mariner before he ever ventured to write fiction. Born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in 1857 to Polish parents in Ukraine, his journeys to the far corners of the earth gave him a firsthand view of late 19th-century European interaction with many foreign cultures in the colonized world. His treatment of this relationship in his fiction is keenly incisive, yet contains flawed and insensitive portrayals of indigenous peoples. Indeed, perhaps his most well-known and widely read work, the classic novella Heart of Darkness, is problematic, to say the least, because of how he depicts the Africans in the story.

Against this backdrop, and during a time of renewed focus on social and racial justice in America, Heart of Darkness could be rejected as not worth reading or as unhelpful to military leaders today. It should not be. The novella is relevant to those who lead or may lead military operations overseas and to those senior policymakers who send them there. In the story, Conrad wrestles with the moral and ethical implications of Western involvement in foreign lands — a subject with which many U.S. military leaders will come face-to-face in the course of their careers. Heart of Darkness also bears directly on the challenge U.S. military leaders confront in ensuring the lawful, ethical, and moral conduct of war. Just as with the story’s mysterious ivory trader, Mr. Kurtz, military personnel have breaking points. Are they at times placed for too long in environments where it is unreasonable to assume none of them will reach theirs? And of these breakdowns, is the environment itself the primary cause or are we indulging a naïve understanding of human nature?

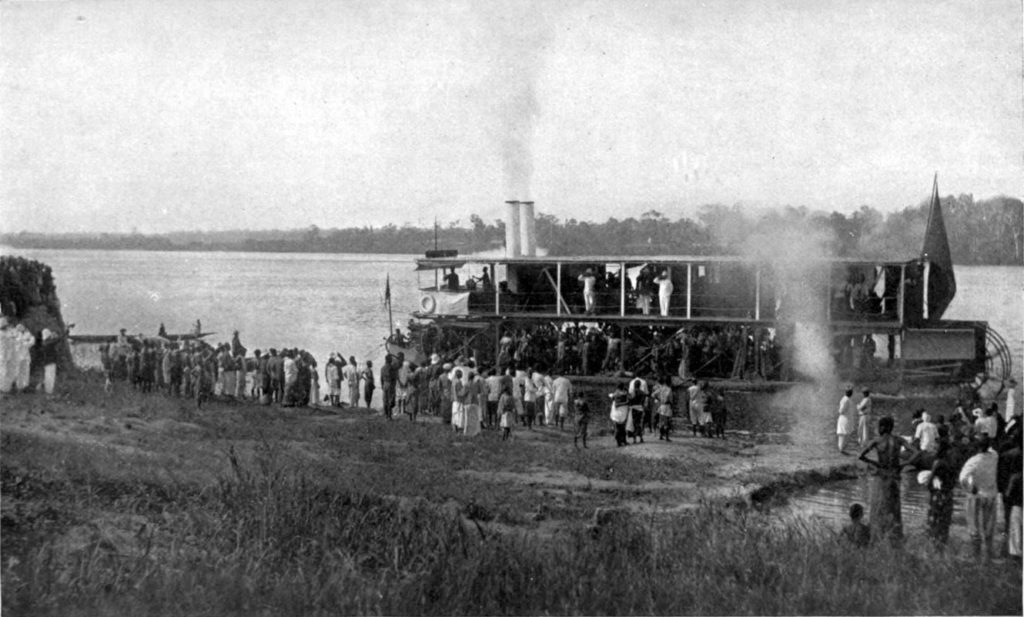

Heart of Darkness is told in retrospect from the cruising yawl Nellie anchored on the Thames. The narrator is Conrad’s alter ego, the merchant seaman Charles Marlow, first introduced four years earlier in Conrad’s story Youth. Marlow recalls to shipmates what he experienced in the Belgian Congo, where, at the behest of a Belgian trading company, he was sent to replace a river steamer captain, a Dane called Fresleven, who was killed by a local chief over “a misunderstanding about some hens.” As Marlow travels up the Congo River, he learns of Kurtz, with whom the company had lost contact and whom the company suspected had gone far into the jungle and found trouble. In my memory of reading the novella in high school in the early 1980s, it was taught as a story about the corrupting influence of the entire European colonial project. No mention was made of the controversy surrounding Conrad’s depiction of the Africans in the story.

Yet, it was just a few years prior that the award-winning Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe ignited this very controversy in leveling a scathing attack on Heart of Darkness, to the point that he labeled Conrad a “thoroughgoing racist” and refused to count it as a great work of literature. For Achebe, only clever, postcolonial literary criticism can look past this serious flaw while claiming the book contains universal lessons — a sort of literary rearguard action meant to protect Conrad’s reputation as a great writer. Conrad may have achieved an artistic, clear-eyed skepticism of man’s true nature, but in Achebe’s telling, that does not absolve him for the offense of perpetuating a racist image of Africa.

Achebe was not the first prominent scholar or person of letters to criticize Conrad’s “colonial” writings. The debate on whether Conrad supported or opposed colonialism had been raging for some time. For example, as Hunt Hawkins noted in his 1979 PMLA article “Conrad’s Critique of Imperialism in Heart of Darkness,” Robert F. Lee, in his 1969 book Conrad’s Colonialism, wrote that “one of the major directions of Conrad’s colonial fiction is a recognition of and accord with the conception of Anglo-Saxon superiority.” Other Conrad scholars, such as Eloise Knapp Hay (The Political Novels of Joseph Conrad, 1963) and Wilfred Stone, believed Conrad was adamantly opposed to the European imperial project and attempts to prove otherwise were, in Stone’s words, “a misreading of Conrad so gross as to be, at times, simply ludicrous.”

As a visiting professor at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, in February 1975 Achebe delivered the lecture “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” (the lecture was later updated and published in The Massachusetts Review in 1977). While the novella may portray Africans sympathetically as people suffering from colonial cruelty and deserving compassion, they were still “savages” from a dark and inhospitable place, and their plight paled in importance to the real problem — the diseased state of the European mind. Marlow recalls the journey on a French steamer to the mouth of the Congo River as traveling “all along the formless coast bordered by dangerous surf, as if Nature herself had tried to ward off intruders. … It was like a weary pilgrimage amongst hints for nightmares.” Africa is a nightmarish place a European enters at his own risk. When Marlow switches to a smaller steamer to take him the first 30 miles upriver, the Swedish captain hints of trouble for those who venture too far into the jungle and wonders why they do it “for a few francs a month. I wonder what becomes of that kind when it goes up country?” When Marlow says he aims to find out, the captain replies that the last man he took up the river wound up hanging himself.

When Marlow arrives at his company’s first station where a railway is being built, he describes a “scene of inhabited devastation. A lot of people, mostly black and naked, moved about like ants.” As he wanders through the camp, he sees at almost every turn evidence of the sheer brutality with which the natives are treated in the service of the trading company’s commercial bottom line:

Black shapes crouched, lay, sat between the trees leaning against the trunks, clinging to the earth, half coming out, half effaced within the dim light, in all the attitudes of pain, abandonment, and despair. … They were dying slowly — it was very clear. They were … nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confusedly in the greenish gloom.

Conrad reinforced a stereotype of a primitive people devoid of their own rich traditions of language, art, and culture. They and the continent of Africa are background props in the story. The black characters barely utter more than a word or two in the whole text. They are nothing but “black shapes” and “black shadows.” They are from the “earliest beginnings of the world,” which for Conrad was not some blissful Garden of Eden where innocence had yet to be corrupted, as Rousseau imagines in Emile, but a time of darkness where man’s base instincts ruled. Achebe writes, “Heart of Darkness projects the image of Africa as ‘the other world,’ the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality.”

Achebe credits Conrad for trying to work out, through Kurtz’s mysterious mental breakdown, what colonization was doing to the European mind and soul, but he rejects the dehumanization of an entire portion of the human race to do it. This powerful rebuke hit like a thunderbolt, sending Conrad admirers and scholars into a defensive crouch. Achebe’s essay, not to mention his debut 1958 novel Things Fall Apart about a fictional southeastern Nigerian tribe that can be read as a response to a European impression of Africa still prevalent in the mid-20th century, makes reading Heart of Darkness today quite uncomfortable, particularly in light of the recent racial justice protests. One cannot ignore some of Conrad’s grimace-inducing descriptions of the African characters and thus could be forgiven for not finishing the novella.

Twenty years after Achebe’s lecture, film and literary critic David Denby revisited the controversy with the essay “The Trouble with ‘Heart of Darkness.’” Denby had just retaken Columbia University’s core literature humanities course (some three decades after he took it as an undergraduate) and later published a book about the experience. In addition to providing an update on the aforementioned controversy, including noting that the Columbia scholar Edward W. Said had joined the roster of critics questioning Heart of Darkness’s place in the canon, Denby pivots to discussing the abiding allure of the classic. He recounts the joy and exhilaration of rereading a text that “has lost none of its power to amaze and appall: it remains, in many places, an essential starting point for discussions of modernism, imperialism, the hypocrisies and glories of the West, and the ambiguities of ‘civilization.’” Denby makes a strong case for rereading Heart of Darkness later in life, perhaps closer to impending experiences for which this particular work may have more direct relevance.

Yet, despite this ongoing literary storm, Conrad’s reputation as an important and unique voice in 20th-century literature seems no worse for the wear. I count myself among those able to reconcile Achebe’s criticism with Conrad’s reputation as a great writer and Heart of Darkness as great literature. Conrad was not Rudyard Kipling, who was perhaps European colonialism’s most eloquent champion, but he still was a product of his day. His blind spots must be weighed in the context of his times, as with any artist. In her widely acclaimed 2017 book The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World, Harvard history professor Maya Jasanoff goes even further, recalling,

When I read [Heart of Darkness] and Achebe’s essay with my own students at Harvard, I came to value Conrad’s perspective … not just despite its blind spots but because of them. Conrad captured something about the way power operated across continents and races, something that seems as important to engage with today as it had when he started to write.

In 2003, the British writer Caryl Phillips, who is black and originally from St. Kitts, ventured to Achebe’s home in upstate New York (by then Achebe was teaching at Bard College) to interview him on his long-standing opposition to Conrad as a great artist. Phillips, a self-described admirer of both Conrad and Achebe, found Achebe thoughtful but unyielding on the subject. In an essay in The Guardian recounting this experience, Phillips writes,

The problem is I disagree with Achebe’s response to the novel, and have never viewed Conrad — as Achebe states in his lecture — as simply ‘a thoroughgoing racist.’ Yet, at the same time, I hold Achebe in the highest possible esteem. … Conrad’s brutal depiction of African humanity, so that he might provide a ‘savage’ mirror into which the European might gaze and measure his own tenuous grip on civilization, is now regarded by some, including Achebe, as deeply problematic. But is it not ridiculous to demand of Conrad that he imagine an African humanity that is totally out of line with both the times in which he was living and the larger purpose of his novel?

Given the ongoing struggles over race in America, including inside the military itself, reading Achebe’s essay carefully and then reading or rereading Heart of Darkness confers a special benefit to military leaders beyond the reasons for which it is usually taught. Achebe’s critique is a perception of the book that I was never taught in school and that I did not appreciate.

That does not diminish the value to military leaders and civilian national security professionals of reading Heart of Darkness in search of Conrad’s larger purpose. But what exactly is it? Military leaders will find Heart of Darkness a helpful and enjoyable aid in navigating the complex ethical and moral terrain of warfare in two important ways.

First, there is the question of America’s role in the world and how that underpins the ostensible reasons for overseas military operations, both in peace and war. Conrad was a severe critic of European colonialism at a time when very few of his contemporaries seemed bothered by it at all. Heart of Darkness was first serialized in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1899, the same year Kipling published the poem The White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands, a draft of which Kipling shared with his friend Theodore Roosevelt, who would, just two years later, become the 26th president of the United States. The poem is Kipling’s call to America to do her duty in civilizing the uncivilized world, which included the Philippine Islands just “liberated” from Spain in the Spanish-American War. For Kipling, colonialism had a noble, even biblical, purpose.

The poem is offensive today, but the belief that the United States has a moral obligation to vanquish tyranny and advance democracy abroad is hardly a thing of the past. Both successful foreign ventures and tragic misadventures have sprung from this well of idealism. The democracy promotion agenda has been derided by many on the left as neocolonialism and on the right as naïve adventurism — different in nature from the rapacious European 19th-century version but still either fundamentally corrupt or just plain stupid and wasteful.

I find both positions extreme and simplistic. Nevertheless, neither should be thoughtlessly rejected any more than one should uncritically hold faith in American exceptionalism. The success of military operations abroad, especially those that last for years, rests in no small way on troop morale, and troop morale rests in no small way on belief in the purpose of the mission. When the troop members stop believing in it, they stop trusting the leaders that sent them into harm’s way, and — as happened in Vietnam — the mission suffers, and there are long-lasting political and societal consequences. Heart of Darkness speaks directly to how misplaced or disingenuous foreign adventurism entrains these consequences. In the case of colonialism in Africa, European populations were fed and largely believed a story about the need to Christianize and civilize native peoples, when the primary objective was exploiting the vast natural resources.

Second, the story bears directly on the challenge of ensuring U.S. military operations are conducted as lawfully and ethically as possible. Perhaps the most enduring puzzle of Heart of Darkness is whether the writer viewed the colonial experience as a causal factor in European man’s corruption and almost inconceivable capacity for brutality or as a consequence of a corrupt and dark nature that simply manifests most vividly in the colonial environment. When U.S. military personnel in war zones lose their way, as happened at My Lai, Haditha, Abu Ghraib, and Bagram, for example, military leaders search for answers, wondering who could be capable of such atrocities and why the system failed to identify them sooner.

But perhaps the better question is, who is not capable of committing a war crime under any conceivable context? Are these instances really the result of “a few bad apples?” The less one believes so, the greater the burden on senior leaders to avoid putting military personnel in morally treacherous environments. What if we are all really savages at heart and the refinements of civilization are tenuous at best at containing the savagery? What if the journey to becoming Mr. Kurtz is far shorter than we care to believe? As Denby notes, his Columbia professor strongly suggested such an interpretation: “‘Savagery’ is inherent in all of us, including the most ‘civilized,’ for we live, according to Conrad, in a brief interlude between innumerable centuries of darkness and darkness yet to come.” Hunt Hawkins too favors this interpretation: “We might suppose that Conrad approved the civilizing mission and objected only when it was subverted by material lust. Conrad makes clear, however, that Kurtz’s immorality is not a contradiction of his morality but an extension of it.”

Conrad’s own experience on the Congo River in 1890 lasted less than six months. He had signed on with a Brussels-based company for three years as a steamboat captain but quit after one round trip between Kinshasa and Kisangani, so traumatizing was the experience.

In his 1998 book King Leopold’s Ghost, Adam Hochschild vividly chronicles the merciless brutality with which the Belgians were administering the Congo Free State by the time of Conrad’s employment there. The Belgian Congo was neither free nor a state, but a vast region for exploitation and murder on a scale shocking even for European imperialism apologists. Leopold’s government largely ran the Congo with criminals and degenerates who enjoyed employing without fear of sanction the most sadistic methods to ensure they met their rubber, copal, and ivory quotas. That Conrad was shocked by this is not in doubt. Heart of Darkness can be read on one level as “one of the most scathing indictments of imperialism in all literature.”

However, Conrad’s critique of colonialism does not adequately explain such an enigmatic text. Conrad, by 1890, had for many years seen “the dirty work of Empire at close quarters,” to quote George Orwell from his 1936 essay on British imperialism, Shooting an Elephant. Yet Conrad did not seem too troubled by British imperialism, as, for example, Hawkins shows by analyzing Conrad’s somewhat conflicted letters on the Boer War in South Africa. He held financial interests in its vast enterprise (by the late 1890s he held an investment stake in a gold mine in South Africa) and was an enthusiastic apostle for his adopted land, an anglophile who believed that “liberty … can only be found under the English flag all over the world.”

Kurtz was not a criminal or a degenerate when he arrived in the Congo. He was an idealist who believed European civilization was a force for good in the world. He studied the native people and wrote a 17-page report for the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs. Kurtz was raised in high society and went to the best schools. It was not until he was long in the jungle and an unwitting tool of a most unholy engine of avarice that his “savagery” gained the upper hand. What happened to Kurtz? Marlow comes to learn that Kurtz had, at some point, scribbled “exterminate all the brutes!” at the end of his report to the Society. As the story unfolds, Marlow and the reader (us) become fellow travelers, increasingly bewildered over the nature/nurture question. We hope that when Kurtz is finally found, he will shed some clarity on this puzzle.

Alas, he does not. Was it just a case of a man cracking under the pressure of living in an inhospitable environment and going insane? Indeed, in describing his 1979 film adaption of the novella on the Vietnam War, Apocalypse Now director Francis Ford Coppola explained that the United States went into Vietnam and went insane (ironically, by many accounts Coppola and some of the cast practically went insane making the film). The implication was clear: Do not go into the jungle. Better to just stay away.

Or was Kurtz complicit in his own descent? Did he yield to a temptation to go where most civilized Europeans dare not go — face-to-face with their own natural amoral savagery, a place where one can make oneself into a god to others and indulge in any desire? Going there and realizing one’s true nature is the ultimate horror — hence Kurtz’s final words, “the horror, the horror,” before dying in the hold of Marlow’s steamer. In Ken Burns’ 2017 documentary on the Vietnam War, novelist and war veteran Karl Marlantes (Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War) seemed to hold this view of human nature: “People talk a lot about how well the military turns kids into killing machines, and I’ll always argue that it’s just finishing school. What we do with civilization is that we learn to inhibit and rope in these aggressive tendencies, and we have to recognize them.” Conrad’s story is a journey into the savage wilderness of our own nature, where Marlow, while searching for Kurtz, discovers the lie “civilized” man indulges to justify the entire colonial project — a lie Mark Twain described as “the white man’s notion that he is less savage than the other savages.”

There’s a case to be made that the U.S. military in recent decades has by many estimates prosecuted war (jus in bello) more justly than at any time in history. Smart weapons may minimize collateral damage, and military personnel observe fairly restrictive rules of engagement. Young military professionals today should not despair but be confident that — if put to the test in the most demanding combat environments — they will serve with dignity, honor, and moral courage. But neither should they nor the leaders that will send them to war take that prospect entirely for granted. When I served in East Africa in 2006, we had to initiate a command investigation of a servicemember in charge of a remote camp accused of selling medical supplies to villagers on the local black market and of illegally hunting rare, protected game. He abused the power he had been given to exploit the local population. While he wasn’t cutting off heads, left alone and relatively unsupervised for months, did he yield in a lesser way to a temptation to make himself into a god like Kurtz had? I think so.

Marlow’s journey up the Congo and Kurtz’s journey into madness retain a metaphorical reach into modern warfare. In reading Heart of Darkness, military and national security professionals should always be mindful that Kurtz is not just a fictional character — he is a warning sign.

Bill Bray is a retired U.S. Navy captain and the deputy editor-in-chief of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine.

Image: Photograph by unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons