How Plummeting Fuel Prices and Reduced Operations Could Free Up Billions of Defense Dollars

The U.S. Department of Defense is one of the world’s largest consumers of petroleum, yet it relies on an industrial-era system to plan for volatility in global oil markets. Prioritizing stability over efficiency, the system is not designed to respond nimbly to shocks in the oil market like the one happening right now due to COVID-19. As global oil prices have dropped from $60 a barrel to the $20s, billions of dollars are becoming available within the Pentagon’s fuel operations for the remainder of fiscal year 2020 and potentially heading into FY2021 — a rare positive in a time of significant uncertainty.

However, who sees this cash — and how much of it — is largely at the discretion of the under secretary of defense (comptroller) and what happens with the Pentagon’s internal “standard fuel price” for fuel products.

To provide insight into this decision, we first describe how the system works by reviewing the energy costs and consumption patterns of the Department of Defense. We move on to discuss how internal pricing and financing occur. And finally, we examine ways in which excess cash may be allocated moving forward. The bottom line is that due to lower fuel prices and reduced operations, the Pentagon is looking at between $2 and $3 billion in excess cash for the remainder of FY2020, shared between the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund and the operations and maintenance accounts of the military services.

Defense Energy by the Numbers

There are significant amounts of money at work in order to support the U.S. military’s fuel and power consumption. The Defense Department’s annual fuel and utilities bill is larger than the of all but 15 countries, putting it in the ballpark of the individual defense budgets of countries such as Iran, Spain, and Turkey. In the last ten years, as the price of oil has fluctuated, the U.S. defense fuel bill alone has ranged from a high of $17 billion in FY2011 to a low of $8 billion in FY2017. The Pentagon also spends around $3.5 billion per year on its utilities bill.

By its own reporting, the U.S. military services estimated they will consume approximately 88 million barrels of fuel in FY2020. Based on its energy-intensive aviation mission, the Air Force is the largest consumer at roughly 52 million barrels a year, or 60 percent of the total. The Department of the Navy — the Navy and Marine Corps — comes in as the second highest user at approximately 26 million barrels a year, about 30 percent of the total. The Army, with little fixed-wing aviation, consumes about 9 million barrels per year.

How the Pentagon Purchases Fuel

The Department of Defense buys both commercial-grade and military-grade petroleum products from the commercial market like everyone else. This means the Pentagon is not financially immune to fluctuations in global oil prices. In order to gain economies of scale and realize operational efficiencies, the Defense Department buys all of its petroleum products centrally through the energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency. By department directive, the director of the Defense Logistics Agency, a three-star officer, is the department’s executive agent for bulk petroleum and can delegate that authority to the commander of the Defense Logistics Agency’s energy branch, a one-star officer. The Defense Logistics Agency oversees the purchase, refinement, transport, storage, and delivery of petroleum products to its military customers throughout the world through a working inventory of about 20 million barrels of fuel. It also keeps a wartime reserve of another 34 million barrels.

The energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency, along with several other agencies, finances its operations through a unique government mechanism known as the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund. According to the Congressional Research Service, a working capital fund functions as a “type of revolving fund that is intended to operate as a self-supporting entity to fund business-like activities.” The Army, Air Force, and Navy also have their own working capital funds. The aim of a working capital fund is to complete the mission while recovering its own costs from customers without pursuing a profit or generating a deficit. The Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund recorded roughly $52 billion in transactions in FY2019 with $12 billion from energy sales, which generated a positive cash balance of $882 million due to lower than anticipated fuel costs.

The fund needs to maintain a revolving cash balance, which totaled $2.1 billion at the end of FY2019, in order to purchase products from the commercial market before charging its military customers upon delivery. As noted in a 2017 U.S. Government Accountability Office report, if cash in the fund is low (below $1 billion), organizations may not be able to make the purchases that are needed. Similarly, in times of excess (above $3 billion), cash can be transferred out by the comptroller or can be rescinded by Congress.

The Standard Fuel Price

While the Defense Logistics Agency buys refined fuel on the open market, it sells fuel to internal defense customers at a constant price, known as a standard fuel price, for each type of product. The use of a standard price mitigates the regular up and down movements in global oil prices. This means the Air Force, Navy, and Army are shielded from volatility in oil markets and have budget stability. It also provides price stability for the Pentagon’s global operations in locations with different delivery costs — from Germany to Afghanistan to Japan.

The standard fuel price is developed from projected fuel prices and from estimates of non-product costs incurred by the Defense Logistics Agency. This latter component ensures the energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency can finance global operations and provide capabilities (storage and distribution operations, transportation, and personnel) that were forecasted to run over $2.5 billion in FY2020. To recover these costs, a “non-product cost” of $25.75 was added to each barrel of oil the Defense Logistics Agency sells in FY2020.

The system works well when prices fluctuate within, say, 20 percent in a given year. But when there are significant and sustained price movements in the oil markets, like this year, the difference between the standard price and actual costs can begin to result in large cash deficits or surpluses. In order to maintain a healthy cash balance in Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund, the comptroller will sometimes change the standard fuel price within a fiscal year.

For example, in FY2018, the standard fuel price was raised from $90 to $115 per barrel midway through the fiscal year. Despite the raise, the energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency posted a cash loss of $1 billion due to higher than anticipated fuel prices that was offset by a $690 million cash transfer via the comptroller. In contrast, in FY2016, there was a reduction in the standard fuel price from $124 to $109 and eventually to $79 per barrel. Despite the two reductions, there were transfers out of the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund of over $3 billion in large part due to a drop in fuel prices that year. The Pentagon experienced similar price volatility from 2009-2013, where it was over or under its original estimates by more than $2 billion per year. In response to a 2014 U.S. Government Accountability Office report, the Defense Department noted,

The challenge remains that rate setting process takes place a budget cycle in advance of execution.[…]The Department does not have storage capacity to hold a year’s worth of fuel purchased in advance, so fuel is purchased in real-time throughout the execution year and sold at a price set 18 months prior.

This places the drop in global oil prices amidst COVID-19 within the context of volatility: The standard fuel price methodology is essentially a clash between the Pentagon’s industrial-era budget planning methodology and a volatile oil market, replete with geopolitical competition and numerous supply and demand variables.

How $2-$3 Billion Will Become Available for the Defense Department

The Pentagon’s annual “revenue,” in the form of the congressionally appropriated budget, is still fully funded. However, the comptroller is facing a high degree of uncertainty in executing the budget for the remainder of the fiscal year due to unplanned COVID-19 related expenses and modifications to operations and training, including reducing large-scale international exercises such as Rim of the Pacific and postponing the Navy’s Large Scale Exercise 2020 for one year. This highlights the difference between budget planning and budget execution, which is where we find significant funds available from fuel.

We can expect two different types of available funds for the remainder of FY2020 and potentially into FY2021. One is the difference between the estimated costs of refined fuel built into the standard fuel price and their lower actual costs today, which is deposited into the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund. The second are unused appropriated funds, primarily with the Air Force and Navy, from not purchasing fuel because of reduced operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. These funds stay with the military services and are not deposited into the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund.

Excess Cash from Internal Fuel Sales

The difference between the budgeted cost of refined fuel products and the actual costs results in excess cash arriving into the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund. Because the Defense Logistics Agency’s average purchase costs were roughly $11 per barrel lower than expected for the first five months of FY2020 prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, we estimated that this resulted in $400 million in cash excess from sales (based on estimated sales of 37 million barrels for that time period). For the last seven months of the fiscal year (March to September 2020), we estimate the average difference between $15 and $40 per barrel. At the low end, this could result in a cash excess of $615 million. At the high end, we found a potential cash excess of $1.64 billion while taking into consideration reduced operations due to COVID-19 (estimating 41 million barrels sold for the remainder of FY2020). When combined with $400 million from the first five months of the fiscal year, this formed a range of total excess cash from $1 billion to $2 billion deposited into the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund for FY2020 if there is no change in the standard fuel price.

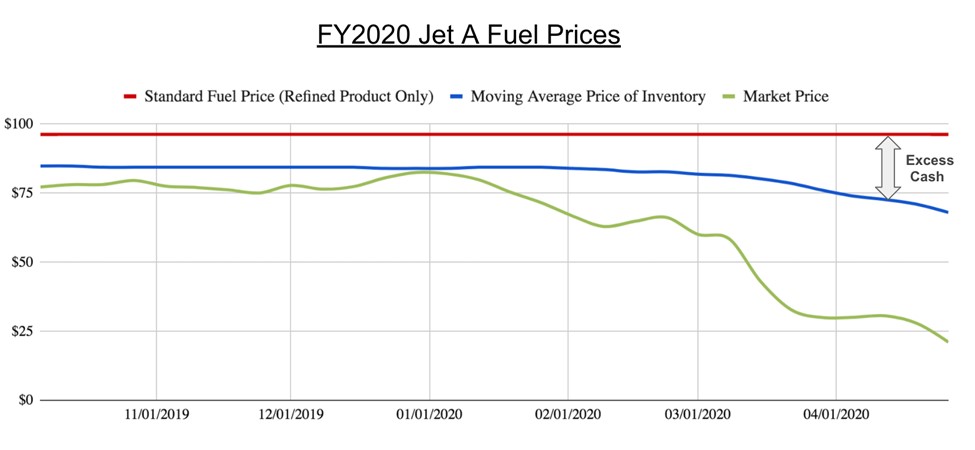

A closer look at Jet A fuel, the largest single fuel product purchased by the Pentagon at 31.2 million barrels in FY2019 and a fuel used by commercial aviation as well as the U.S. military, highlights the potential for excess cash. For FY2020, the refined product cost for Jet A fuel built into the standard fuel price is $96.32. To compare that versus actual costs, we use the moving average price, which is the “average purchase costs of [the Defense Logistics Agency’s] inventory” for each fuel and is updated weekly on its website.

Note: All prices are per barrel, standard fuel price and moving average prices are for Jet A Fuel, Market price is for U.S. Gulf Coast Kerosene-Type Jet Fuel Spot Price FOB. Source: standard fuel price, moving average price, market price.

As illustrated above, the solid red line shows the Pentagon’s forecasted cost of refined product for Jet A fuel at $96.32 (remember, the non-product cost of $25.75 is added separately into the total standard fuel price). The blue line charts the moving average price — the average cost of inventory for the energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency — for Jet A fuel. Through early February, this was around $84 per barrel, producing a cash excess of $12 per barrel. The green line charts the market price for U.S. Gulf Coast kerosene-type jet fuel, one available fuel benchmark. However, with the drop in fuel demand due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we begin to see the market price for jet fuel plummet. As jet fuel prices (green line) fall, this then pulls the Pentagon’s moving average purchase price (blue line) down. At the end of April, this was producing close to a $30 excess for each barrel of Jet A fuel sold by the energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency, and it is expected that the moving average price will continue to decline while market prices remain low. While this example looks at Jet A fuel, the spread between the refined costs within the standard fuel price and the moving average price will be different for each fuel product that the energy branch of the Defense Logistics Agency sells.

Available Funds from Fuel Not Purchased

Fewer fuel purchases due to a reduction in operations means that those appropriated funds remain unspent by the military services. At the beginning of FY2020, for example, the Air Force expected to spend over $6 billion on fuel based on its projected consumption (roughly 52 million barrels) and the standard fuel prices.

We examined what this looks like from an energy perspective, noting that a difference between the projected annual fuel consumption of the military services’ and the actual amount consumed is common, as explained in a 2016 U.S. Government Accountability Office report. In order to estimate the amount of unspent appropriated funds for fuel, we first calculated the amount of barrels not purchased by applying a straight-line 20 percent reduction in operations and associated budgeted fuel burn due to COVID-19 from March through September, the end of the fiscal year. This resulted in 10 million barrels not purchased across all the military services due to reduced operations. Next, we applied a standard price of $124 per barrel for all barrels not purchased, because 85 percent of energy sales to the military services are derived from five fuels (Jet A, Jet A-1, JP5, JP8, and F76), each of which have standard prices within $2 of $124 per barrel.

This resulted in $1.2 billion in available appropriated funds. This included 6 million barrels not needed by the Air Force (saving $744 million), 3 million barrels by the Navy ($372 million), and just above 1 million barrels by the Army ($124 million). A higher pace of operations would increase fuel consumption and reduce available funds, while a lower pace of operations would reduce fuel burn and increase available funds. These funds would remain in their current location, which is generally the operations and maintenance accounts of the military services to which they were appropriated. Therefore, the military services can reinvest these unspent fuel funds into other priorities within their respective operations and maintenance accounts.

Moving Forward: Watch the Standard Fuel Price

The amount of excess cash, and who gets it, largely depends on one thing; the standard fuel price. If the standard fuel price stays the same, it could be for a variety of reasons. One is the total cash position of the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund. Because other organizations, including the supply chain management branch of the Defense Logistics Agency, use the same fund, even if the energy branch’s operations were resulting in large cash flows into the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund, these could be offset by losses in other organizations supported by the same fund. Another is that the comptroller may wish to allow cash to accumulate in the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund to enable flexibility with emerging priorities during the remainder of FY2020, such as paying for COVID-19 healthcare-related expenses. This would be closer to a wait-and-see approach, allowing for flexibility over time.

If the comptroller reduces the standard fuel price and aligns it closer to actual costs, it means that there has been a decision to return cash to the military services, who will pay less for the same amount of fuel. This could also impact competing service priorities as flight qualifications and training would be cheaper to achieve. It also implies that the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund has enough cash reserves to fund its operations as a lower standard fuel price means less excess cash deposited in to the fund.

Given these options, and the drastic drop in oil prices, it would not be surprising to see a modest decrease in the next month to the standard fuel prices with lower moving average prices, shifting some value up front to the services while ensuring financial flexibility for other Pentagon priorities, such as the COVID-19 response, throughout the remainder of the fiscal year.

A Rare Positive

Price volatility in the oil market is responsible for some of the largest variances in the defense budget. As this fiscal year continues, our research indicates that $2-$3 billion — shared between excess cash deposited into the Defense-Wide Working Capital Fund as well as available funds with the military services — will be realized and can be reinvested into other priorities, a rare positive amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. While significant, this is a product of a unique defense budgeting and execution system: The standard fuel price provides budget planning stability and mitigates price impacts to the military services, but in the year of execution, it also dulls price signals along the entire sales and policy chain.

Surprisingly, it does not take a global pandemic to have billions of excess cash appear within the Pentagon’s fuel operations. The system is designed to provide reliability at the expense of cost efficiency. Until it is reformed, the interplay between budgeted fuel costs and what actually happens in the year of execution will continue to cause billion-dollar swings.

Michael Baskin is currently a non-resident fellow at the Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines. He previously served as a fellow in the U.S. Department of Energy, where he was a liaison to the U.S. Department of Defense, and as the first professor of energy studies for the Marine Corps. He holds a Ph.D. from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and served as a U.S. Army infantry officer in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Konrad Gessler is an entrepreneur and former management consultant. He holds a B.A. in international relations from Tufts University.