Light Touch, Tight Grip: China’s Influence and the Corrosion of Serbian Democracy

If you visit Belgrade this fall, you may catch a glimpse of Chinese police officers on patrol in heart of the Serbian capital. With little public attention, China’s influence in Serbia has significantly expanded in recent years. Serbia’s fragile democracy allows China’s economic interests to grow relatively unchecked, while support to Serbia’s political elites in turn encourages its undemocratic tendencies.

As concern in much of Europe about China’s economic and political influence has grown, Beijing’s engagement with Serbia, the geographic heart of the Balkans, has increased rapidly. In a recent interview with Reuters, Serbia’s minister of infrastructure Zorana Mihajlović lauded the country’s receipt of almost €5 billion ($5.62 billion) in investment financing and loans from China, while promising a new influx of funds. China’s motivations for this engagement are straightforward: It sees the Balkans as a key door to Europe’s broader market, and Serbia lies at the geographic and strategic heart of the region.

The forging of a Sino-Serbian relationship is made possible by the fact that China and the Chinese Communist Party remain little understood in Serbia. The public maintains a mostly positive view of China, based on Chinese investment in Serbia’s development and a lack of knowledge about the opaque terms of such deals. The public also is largely uninformed about the Chinese Communist Party and how it exerts influence abroad.

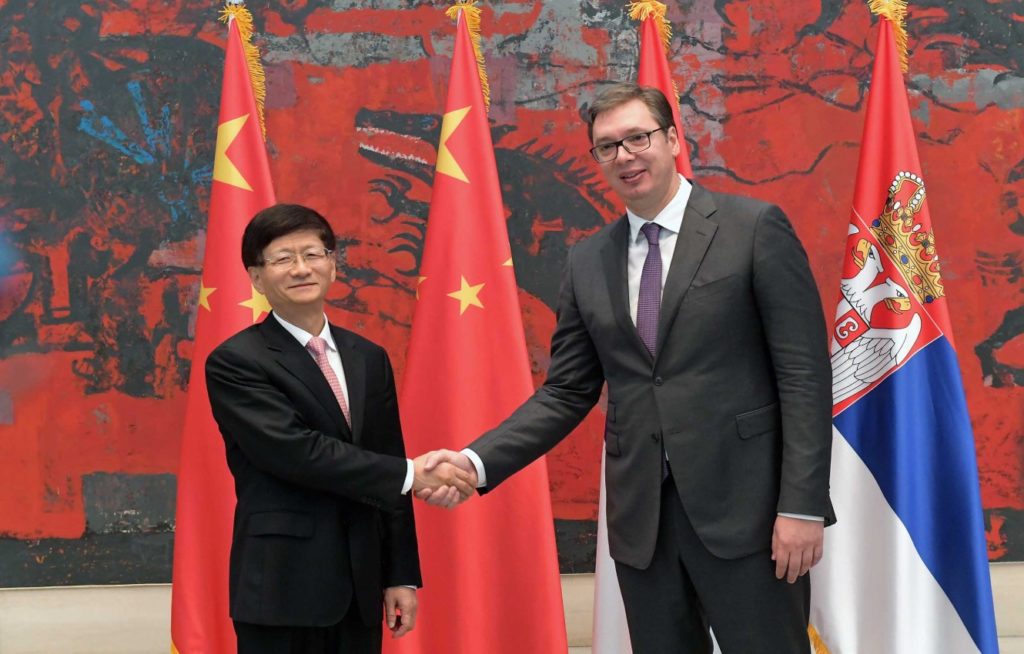

The growing power enabled by this filtered view of China, while beneficial to both parties economically, has spilled over into the political sphere; benefitting from, but also abetting, an increasingly illiberal Serbian government. The current government, led by President Aleksandar Vučić, welcomes Chinese investment as a boon to its political fortunes and controls the media narrative about the bilateral relationship. Vučić and his Serbian Progressive Party increasingly control government agencies, the national security apparatus, and the media, leading Serbian politics in the direction of “soft autocracy.”

Rapidly Increasing Economic Influence

China’s economic engagement with Serbia has grown steadily in response to Serbia’s dire need for financing and infrastructure improvement and China’s drive for strategic investments in the Balkans. China’s engagement with Serbia was limited before 2009, when the two countries signed a strategic partnership agreement. The relationship started to transform in the mid-2010s, when Serbia began receiving significant Chinese financing for infrastructure projects. The Export-Import Bank of China financed the construction of the Pupin Bridge across the Danube River in Belgrade, the first major Chinese infrastructure project in Serbia. The bridge, constructed by the Chinese state-owned enterprise China Road and Bridge Corporation, was completed in 2014.

China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative ushered in a major influx of Chinese financing in Serbia, particularly following Chinese President Xi Jinping’s historic visit to Serbia in June 2016. On that occasion, it was agreed that China’s Hesteel Group would take over from the Serbian government a steel mill based in the city of Smederevo that was at one point also owned by U.S. Steel. In August 2018, the Chinese mining company Zijin Mining acquired a 63 percent stake in debt-ridden RTB Bor, the only copper mining complex in Serbia. RTB Bor, like the Smederevo steel mill, is considered part of the foundation of Serbia’s industrial capacity, and both are major employers in Serbia. In a 2018 research interview I had with him, Branislav Mihajlović, an opposition politician and former employee of RTB Bor, has claimed that “the entire Serbian mining industry was sold to the Chinese for free.” In reality, the acquisition cost China $1.26 billion, but Mihajlović’s statement speaks to the opposition’s concern that the sale was below market value, and suggests a lack of transparency in Sino-Serbian economic agreements. Russian and Canadian firms also bid on RTB Bor but were not selected, further underscoring the closeness of Sino-Serbian ties.

In September 2018, Vučić met Xi at the World Economic Forum in Beijing (their fifth meeting in as many years) to sign commercial agreements worth $3 billion. These included deals for a Chinese company to build a tire factory in Zrenjanin, Serbia, and the purchase of Chinese military drones by Serbia. China Road and Bridge Corporation’s parent company, China Communications Construction Company Ltd., is also currently engaged to construct another bridge over the rivers Kolubara and Sava, financed by the Export-Import Bank of China.

Chinese engagement with Serbia has raised hopes of improved local infrastructure and employment opportunities. However, the opacity of these deals has raised concerns among private enterprise, civil society, and others that Chinese lending could create unmanageable debt loads and future Chinese leverage over the country. Most of the commercial contracts with Chinese entities are not available to the public, with little opportunity for public review and comment.

Unlike in many other Belt and Road Initiative countries, Chinese state-owned enterprises in Serbia have not insisted on using only construction material imported from China, probably due in part to Serbian government conditions. For instance, the contract for the construction of the Pupin Bridge mandated that 45 percent of the construction material originate from Serbia. However, Chinese state-owned enterprises have employed predominantly Chinese machinery and workers, reducing the benefits of projects to local employment and the economy. The visa regime between Serbia and China was liberalized in 2017, contributing to a rapid increase in the number of Chinese tourists.

The most prominent Chinese project in Serbia is the high-speed railway connecting Belgrade with Budapest, Hungary, inked in 2013. However, little progress has been made on implementation, raising questions about the project’s utility and feasibility. Despite this disappointing progress, the high-speed railway has been touted as “the signature project of the 16+1 framework,” a grouping established by China to facilitate cooperation and economic engagement between itself and Central and Eastern European countries, including Serbia. Through the 16+1 mechanism (now 17+1 with Greece) China has pledged billions in credit and investment for the region, and for Serbia in particular.

Serbian demand for infrastructure financing from China is reinforced by delays in Serbia’s progress toward European Union accession. The country cannot currently use E.U. funds such as the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance, designed to provide E.U. “enlargement countries” with financial and technical help, for infrastructure projects. China also gains relative advantage because Chinese funding, unlike that from the European Union, is disbursed quickly.

China’s ability to ensure that such funding correlates with Serbian political cycles offers opportunities for corruption and enhances China’s influence with elites. Serbian politicians of all parties able to secure Chinese financing around election time can promote themselves to their constituents as enablers of Chinese capital inflows. Many of those same politicians and elites find the lack of transparency in Chinese funding appealing, creating rent-seeking opportunities.

Friends in High Places

The Chinese Communist Party goes to great lengths in many countries to shape the information space to ensure a positive view of China’s engagement. In Serbia, however, China has not needed to aggressively influence debate about its impact on Serbia despite its increasing economic presence in the country. China’s activities are perceived as largely benign by the Serbian public.

The government — led by Vučić, who has called the friendship with China one “made of steel” — helps to ensure this positive view of China through its control over the information and media sphere. Most Serbs get their news from television, where most advertising money in Serbia is spent. There nevertheless remains a shortage of capital for most major outlets, making almost all of them dependent on state funding and subject to government influence. This ensures largely positive coverage of China’s ruling party. Government-friendly media also does not report news that critically examines China’s role in the country. The Serbian media, echoing the country’s political leadership, typically (and incorrectly) presents Chinese financing as “gifts,” not loans.

Consequently, China can rest assured that under the Vučić administration relatively little critical information on Chinese activities will surface in outlets that influence Serbian public opinion. Those programs that do appear on Serbian media concerning China are typically overwhelmingly positive. In 2017, the national broadcaster Radio Television of Serbia ran a series of Chinese government-produced television documentaries on China, including one on the Silk Road. Even among the Serbian opposition there has not been significant criticism of China in the media.

The Chinese Communist Party has sought to further enhance this positive view by cultivating ties with cultural and political elites (including the political opposition) and establishing institutions that could help shape the narrative about China in the future. China supports the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development, a think tank led by a former Serbian foreign minister and opposition politician Vuk Jeremic, which holds events and releases publications about the benefits of the Belt and Road Initiative and the expanding China-Serbia relationship. The institute is partly funded through CEFC China Energy, a conglomerate linked with Chinese Communist Party and mired in corruption scandals.

As in many countries, Serbia hosts two Chinese government-sponsored Confucius Institutes promoting Chinese culture — and official government viewpoints — at prominent universities in Serbia, and China is investing €45 million to build a cultural center on the site of the Chinese Embassy building destroyed during the NATO air campaign in 1999.

The role of Chinese technology firms in Serbia, and their potential role in the country’s surveillance ecosystem, present another avenue of potential influence for the Chinese Communist Party in the country. Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei has a cooperation contract with Serbian telecommunications company Telekom Srbija, and the Serbian government has signed a contract that would allow Huawei equipment to be used for traffic surveillance. The Serbian Interior Ministry has contracted with Huawei to provide cameras and facial recognition software for its “Safe City” project and announced the planned installment of a thousand cameras in 800 locations in Belgrade. The ministry did not, however, explicitly cite Huawei as a supplier, possibly to avoid attention given the sensitivity surrounding the company and its ties to the Chinese government.

Pushing on an Open Door

The illiberal tilt of Serbian politics, characterized by Vučić’s growing domination of the political scene and its institutions since 2012, has facilitated China’s integration into the Serbian economic and political landscape. Vučić and the Serbian Progressive Party-led government allow for one point of focus for Chinese state-owned enterprises and government lobbying resources. Serbia’s “soft autocracy” provides few roadblocks to Chinese influence, with very few institutional or societal checks on China’s influence or insistence on greater transparency in negotiations with Serbian officials. The lack of Serbian expertise in both academic and policy circles on China and the Chinese Communist Party’s means of influence ensure limited public debate about the risks of opaque Chinese investment deals and growing coziness with the ruling government.

China’s influence, in turn, has indirectly facilitated Serbia’s tilt toward soft authoritarianism by bolstering the fortunes of illiberal Serbian leaders who use the influx of Chinese investment to promote themselves domestically as those who can deliver needed infrastructure development. That way, China helps the extant political climate by providing the incumbent political elite with another source of domestic legitimacy. To be fair, the cornerstone for this new Sino-Serbian partnership was set by a pro-EU, left-center government in Serbia back in 2009 that signed a strategic partnership agreement with China. However, the fact that this partnership flourished under the current illiberal government has helped the powerholders in Belgrade to instrumentalize its relationship with China as a way of domestic promotion. In turn, declining rule of law and an increasingly illiberal political environment under the Serbian Progressive Party make it easier for China to grow both its investments and its influence.

China’s growing and opaque investments in the country and tight relationship with the current government point toward potentially negative consequences for Serbia’s increasingly fragile democracy. The Serbian Progressive Party-led government appears inclined to pursue even closer ties with China. In 2017, the Serbian government established the National Council for Coordination of Cooperation with the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China, led by former Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić (2012-2017), who is also from the ranks of Serbian Progressive Party. This new government office may represent yet another channel of potential influence for the Chinese Communist Party going forward.

Despite China’s growing influence in Serbia, a nascent but growing awareness of the risks of expanding, unscrutinized Chinese economic engagement with the country and the Chinese Communist Party’s cultivation of the ruling government provides a foundation for resilience to China’s influence. A key test of Serbian resilience to future Chinese Communist Party’s influence may emerge if controversy arises over one or more Chinese infrastructure projects. Given government controls on information and the lack of unity among unions and labor advocacy groups, it currently appears unlikely that Serbian society will be able to organize resistance in such a scenario. Greater knowledge of China’s influence tactics and the capacity to counter them across Serbian civil society and remaining independent media are critical to better protecting this increasingly weak democracy. Because of Serbian self-interest, its partnership with China will survive even the potential change in Serbian leadership. However, precisely because of Serbian political self-interest, a better understanding of China is needed to ensure that Serbia can manage its partnership with China in a way that will help it insulate itself from any risks. Seeing China’s relationship with Serbia for what it is will probably involve a partnership between international institutions and domestic stakeholders in Serbia, such as representatives of civil society, remaining independent media, and academics, with the purpose of initiating a more nuanced and balanced debate on China. One thing is for certain, if nothing changes, China is in the driver’s seat.

Vuk Vuksanovic is a PhD researcher in International Relations at the London School of Economics. He previously worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Serbia and as a political risk consultant in Belgrade. He writes widely on modern foreign and security policy issues, and is on Twitter @v_vuksanovic. The piece is derived from the report chapter he authored for the International Republican Institute (IRI).

Image: Serbian Ministry of Defense