Why Not a Space Force? Cautions of Organizational Re-Design

What might congressional hearings with the chief of staff of the U.S. Space Force sound like in 2035? The chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee might begin the questions with:

The Space Force headquarters staff has doubled in size since 2020, we’ve conducted offensive space operations independently twice, sparking a ground war and a trade war, and the other service chiefs report that our near-peer adversaries have surpassed us in integrating multi-domain operations, especially space capabilities. General, my first question is, were any of these outcomes predictable, and how have they been influenced by having a separate Space Force?

Last month, President Donald Trump signed Space Policy Directive-4, directing the Department of Defense to draft a legislative proposal to establish a Space Force by 2020 as a sixth branch of the armed services under the Department of the Air Force — similar to how the Marine Corps is its own military service under the Department of the Navy. The directive makes clear this is an interim step toward eventual full independence for the Space Force: “As the United States Space Force matures, and as national security requires, it will become necessary to create a separate military department, to be known as the Department of the Space Force.”

Organizational design theory predicts several worrisome outcomes of a Space Force created either as a separate service or an independent department. The granting of independence to the U.S. Air Force in 1947 and the establishment of U.S. Special Operations Command in 1987 share striking similarities with the Space Force debate in terms of the general security environment and the specific re-organizing proposals. In each case, unique mission sets were differentiated at the highest levels — that is, they were insulated from outside control and elevated within the organization.

Space Force could be the next success story to follow this pattern, but organizational design theory and historical experience provide a few cautions regarding growth of headquarters staffs, eased access to senior leaders, resistance to integration, and unmanageable span of control. The benefits of a Space Force, either as its own department or as more modestly proposed by the president’s directive, may well outweigh these cautions, but they deserve careful consideration and attention to potential mitigating strategies.

Growth of Bureaucracies

The first reason to be cautious is that a new organization takes additional overhead, and the size of that overhead grows predictably. A Space Force will need a headquarters staff with executive-level administrative staff, legal counsel, congressional liaison, and public affairs. Even if initially manned by transferring existing billets, history predicts the staff size will grow.

Historian C. Northcote Parkinson studied the size of two British bureaucracies, the Navy Admiralty and the Colonial Office, and concluded that staff accumulation occurs naturally with no relation to the amount of work to be done. Following the natural proclivity to enhance their own importance while trimming the amount of work they have to do themselves, bureaucrats at all levels of organizations tend to increase their number of subordinates. Increases in the number of employees add to managerial workload and coordination, as employees tend to create work for each other. Based on his research, Parkinson declared Parkinson’s Law: For administrative departments outside of wartime, staff size tends to increase at an average rate of 5.75 percent per year.

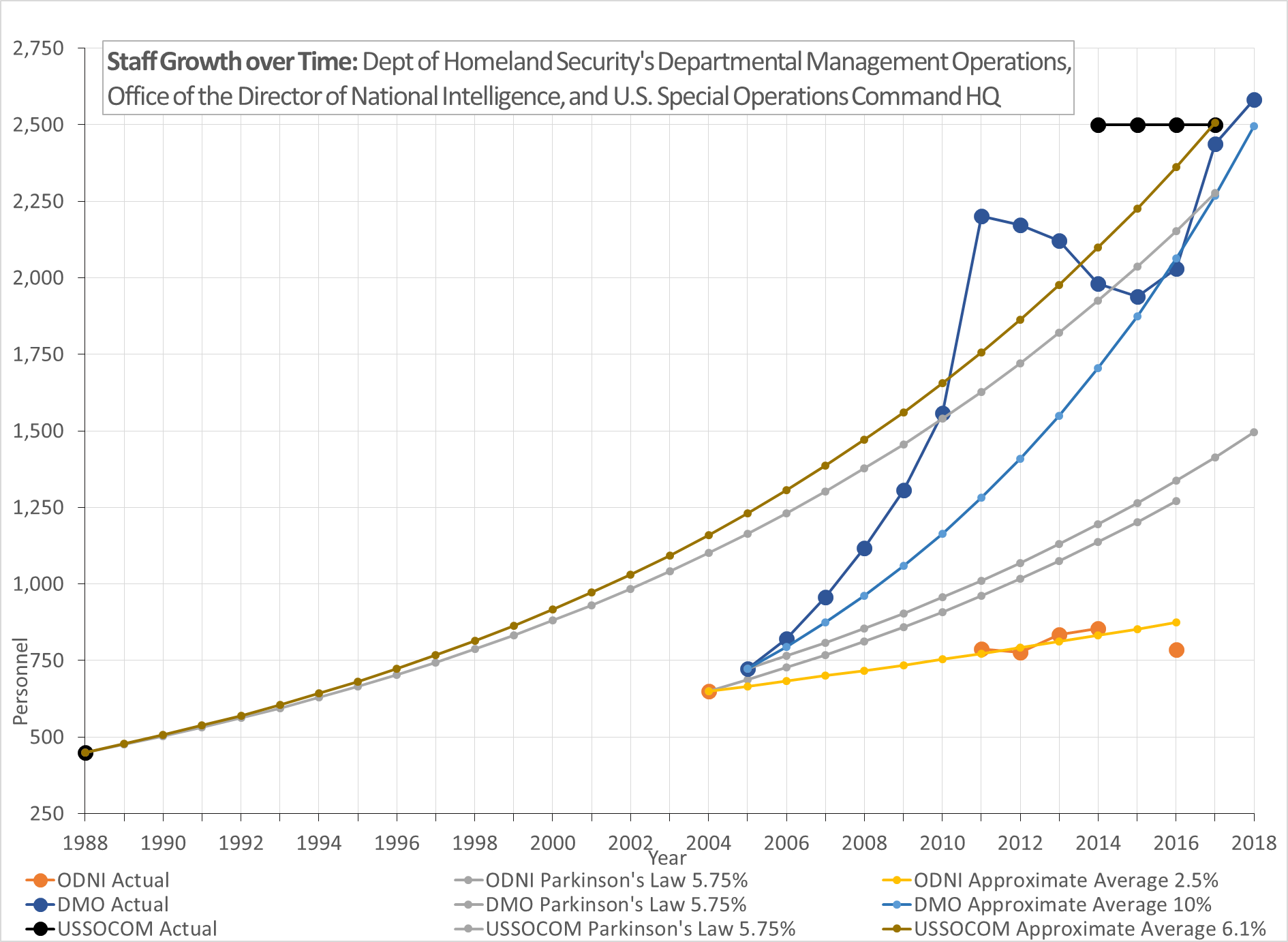

The Department of Homeland Security provides a modern example of Parkinson’s Law. Since the Homeland Security Act of 2002 established the department, the staff size of its Departmental Management Operations has grown considerably. In 2005, this office consisted of 723 personnel comprising the Office of the Secretary and Executive Management Offices, under secretary for management, chief financial officer, and other staff chiefs. The department’s 2018 budget described this office with the same basic responsibilities but included nine additional subordinate staff offices (including the Office of Legislative Affairs, Office of Public Affairs, Office of the General Counsel, and Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans). By 2018, the staff had grown from 723 to 2,582 — or 10 percent annual growth.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence reminds us that new organizations require additional overhead. The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 established the director of national intelligence as the head of the intelligence community and detailed the makeup of the office, including the director, principal deputy director of national intelligence, national intelligence council, general counsel, national counterintelligence executive, up to four deputy directors, and permanent, professional staff to assist the director. Each of these positions was new and simply establishing the office required a growth in overhead.

Beyond initial growth, the staff also grew over time. Congress initially authorized 500 new positions in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and approved up to 150 for temporary transfers from other organizations, totaling 650 personnel in 2004. The 2016 Intelligence Authorization Act authorized 785 personnel for the same office, including those detailed from other agencies. The annual staff size growth from 2004 to 2016 was approximately 2.5 percent — lower than Parkinson’s Law predicts, but still growth.

The Nunn-Cohen Amendment to the 1987 National Defense Authorization Act established U.S. Special Operations Command as a combatant command with service-like authorities, and its headquarters staff has grown since its inception. Legislation for fiscal year 1988 mandated a headquarters staff of at least 450 personnel. Many of these original billets transferred from the simultaneously deactivated U.S. Readiness Command, creating some efficiency in standing up the organization. By 2017, the size of the headquarters staff was approximately 2,500 personnel — averaging 6.1 percent growth. The figure below charts all three examples’ growth with available data.

Parkinson’s Law predicts a Space Force will increase cost and reduce the organization’s effectiveness. Given a finite budget, the only way a Space Force will be able to grow its headquarters staff will be to take positions away from research labs or operational units, limiting either modernization or readiness. The alternative would be an increase in end strength and therefore an even greater budget. Either way, a Space Force will likely lose some of its bang for the buck over time. However, Congress can prevent headquarters staff growth by ensuring all necessary functions are defined and established from the outset. This would be an atypical stance from Congress to insist the headquarters staff is large enough rather than trying to build the organiztion on the cheap. Getting the organization sized right from the beginning would help justify an end strength cap on the new headquarters size and prevent unecessary growth.

Ease of Access

Differentiation doesn’t just create growth of bureaucracy — it can also change how leaders employ the new organization, because creating a new organization by definition provides its leaders with more access to senior decision-makers. A Space Force’s four-star chief of staff will not only have a seat among the Joint Chiefs of Staff but also the legal right to provide individual advice directly to the president and National Security Council. Under the status quo, on the other hand, any advice from Air Force space advocates flows through the Air Force chief of staff, who maintains a broader perspective due to overseeing a more diverse organization. Elevating a Space Force — either to quasi-independent status or to a fully independent department — will allow unfiltered opinions to reach the top that might have otherwise never survived the march up the chain of command or would have been altered as they were integrated into a wider strategy.

While in some cases direct access to the president by a Space Force chief of staff would certainly be useful in providing guidance on strategic matters related to space, planners should also consider how this access could lead to military action in the space domain devoid of a broader strategy. The growing use of special forces illustrates the challenge presented by enhanced access.

In Commandos and Politicians, written a decade before U.S. Special Operations Command was established, Eliot Cohen warned politicians of the allure of reaching for clandestine, deniable special operations to achieve tactical victories with instant strategic results. Despite this appeal, Cohen wrote with a seeming sigh of relief, “For the most part, however, we can rely on the natural proclivities of the regular military and civilian defense bureaucracies to squelch overeager elite units.” Since the Nunn-Cohen Amendment established U.S. Special Operations Command, there has been a four-star combatant commander reporting directly to the national command authorities. This offers much less opportunity for the defense bureaucracy to “squelch” the use of special forces or at least to ensure their employment is woven into a comprehensive strategy.

With this access, special operations forces have been used more often since the command’s inception — and more so since September 11, 2001. Their increasing use has led some to claim special operations forces have become the “easy button” and to question whether these activities are nested in a broader strategy, especially considering the mixed results in headline-making events in Mogadishu and, more recently, Niger.

Special forces offer leaders the ability to take actions that are plausibly deniable and put few soldiers directly in harm’s way. The space domain is strikingly similar. Offensive action from space, especially against other space assets, would be extremely hard to attribute to the actor and would seldom involve boots on the ground. With space advocates in the Situation Room voicing their opinions directly to the president, the temptation to take tactical action will be strong. Moreover, since military conflict in and from space is still a developing concept, politicians will have less experience to draw on when making decisions.

Colin Gray has recorded how early airpower advocates built up unrealistic expectations for the independent use of airpower. This behavior is predictable, Gray concludes: “When a new form of war is analyzed and debated, it can be difficult to persuade prophets that prospective efficacy need not be conclusive.” If a Space Force follows historical patterns, giving the Space Force secretary or chief of staff unfiltered, direct access risks the president taking military action in or from space that could result in negative strategic consequences.

Departmental Resistance to Integration

Differentiated organizations tend to resist integration with other departments — often counter to higher organizational goals. As units within an organization become specialized, so does their thinking. Members of each department develop attitudes and behaviors consistent with their unique group identity, interests, and point of view. Specialized viewpoints provide value in many ways, but disparate attitudes and behaviors can also lead to negative consequences if not properly managed. For instance, military research and development units can produce exquisite systems with incredible capabilities, but if they are too expensive to field in sufficient quantities, the effort is unsatisfying to operational units. Gareth Morgan noted that specialization can lead to “empire building, careerism, the defense of departmental interests, pet projects, and the padding of budgets . . . [that] may subvert the working of the whole.”

Samuel Huntington described how the typical military officer “tends to stress those military needs and forces with which he is particularly familiar. To the extent that he acts in this manner, he becomes a spokesman for a particular service or branch rather than for the military viewpoint as a whole.” This natural bias in specialized viewpoints results in conflict between units within an organization as departmental goals overtake overall organizational goals.

Even under the same service, space professionals and traditional airmen operated in different worlds for decades with little common outlook or interaction. This caused a lag in exploiting military opportunities in space, especially using space-based assets to enhance air operations. Gen. Charles Horner, a fighter pilot who commanded the Air Force’s Space Command after Desert Storm, realized this divide and attempted to force the two worlds to interact. To mitigate the divergence of specialized organizations, he fielded space support teams, who embedded with air operations planners to provide space expertise. He also stood up the Space Warfare Center in 1993, staffed with both space and air experts, to explore applications of space in modern warfare. With these mechanisms in place, integration of air and space operations took a rapid leap forward in the 1990s. Separating the Space Force from the Air Force — even if still under the Department of the Air Force — risks undoing much of the integration Horner’s reforms achieved and preventing future integration. It is unlikely the Space Force will ever be commanded by an Air Force general — no one would ever appoint an admiral as commandant of the Marine Corps. Raising the organizational barrier between the specialized worlds, which were already difficult to integrate, will greatly increase the need for mitigating strategies like support teams and warfare centers.

Span of Control

Finally, with only so many hours in a day, there are only so many subordinates one person can effectively supervise. The number of direct reports assigned is defined as the “span of control.” Adding a new specialized department to an existing organization creates an additional direct report to manage, increasing the span of control.

The secretary of defense has an extremely wide span of control including a deputy, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, three military department secretaries, ten combatant commanders, and 15 principal staff assistants who report directly to the secretary or deputy. A Space Force department would add one more direct report, a political appointee with responsibility for a new, disparate organization for a highly technical function. Trump’s proposal of a Space Force under the Department of the Air Force would similarly challenge the secretary of the Air Force with a wide span of control. The secretary already directly oversees an undersecretary, four assistant secretaries, four principal staff executives, and the chief of staff of the Air Force. A Space Force would add another chief of staff and undersecretary.

Harvard Business Review notes that CEOs of Fortune 500 companies have doubled their spans of control in the last 20 years and now average 9.8 direct reports. The same article also advises reasons for a larger or smaller span. Organizations requiring a lot of cross-department collaboration are better suited for smaller spans. Integrating space capabilities with other warfighting domains certainly qualifies as an activity that demands collaboration and therefore a smaller span of control. Too big of a span can can affect an organization’s morale, effective decision making, and flexibility. This suggests a Space Force under the secretary of the Air Force might be better positioned for success than a department under the secretary of defense, though the impact on the Air Force chief’s bandwidth is still a risk worth examining.

Adding subordinates has a disproportionate impact on a supervisor’s responsibilities, because each adds exponentially to the number of subordinate interactions to manage. The last time the nation added a new military service, the Air Force, it also established a much larger overhead organization — the National Military Establishment, later renamed the Department of Defense. Space Policy Directive-4 makes no similar adjustment and will only spread the secretary of the Air Force even thinner. Whether a service or a department, the Space Force will demand extraordinary supervisory attention at the highest levels where time is already a precious commodity.

Implications

Organizational independence is not a panacea. Creating an independent Space Force may trigger predictable growth in staff size, create disproportionate ease of access to specialized advice, increase departmental resistance to integration at the expense of the entire organization, and strain the limits of an effective span of control. Getting the organization wrong could waste taxpayer dollars, hinder progress toward multi-domain operations, or even risk triggering a war if the president takes military action from space after a whisper in his ear from an overeager Space Force chief of staff looking to prove the new service’s value. None of these outcomes is guaranteed. Carefully considering the right organization and developing mitigating strategies for predictable outcomes can help manage varying viewpoints, deal with natural conflict, value diverse input, and create processes to integrate them together toward organizational goals.

Some of the same arguments expressed here were voiced against independent air forces and greater autonomy for special forces, yet both were successful. Despite the cautions expressed here, the Space Force may be the next great success story alongside the National Security Act of 1947 and the Nunn-Cohen Amendment. But there are real drawbacks to this high level of differentiation that Congress and the administration should consider, making their decisions with eyes wide open.

Col. Kevin L. Parker is an active duty Air Force officer currently serving as a group commander. He holds a PhD in military strategy from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Air Force illustration by Airman 1st Class Dalton Williams