George H.W. Bush: American Radical

Since his death, George H.W. Bush has been praised for his steady and prudent statesmanship at a time of global turbulence. This view isn’t wrong, but it is incomplete: Bush’s conduct may have been even-keeled, but his foreign policy was anything but. In fact, Bush oversaw the greatest transformation of American foreign relations since World War II.

Most Americans take it for granted that the United States should play a large role in global affairs. This attitude, however, is a recent development. After all, the United States came home after World War I, was reluctantly dragged into World War II, and — as the Cold War ramped up — the American public and policymaking elite alike had to be convinced to remain actively engaged in Europe and Asia. It was therefore not obvious that the United States would remain invested in Europe, Asia, and beyond as the Cold War ramped down. Take away the Soviet threat — so a powerful line of argument went in the late 1980s and early 1990s — and the United States could and should reduce its overseas commitments.

With the Cold War over, there was a good case to be made that the United States should revert back to its traditional disengagement. Indeed, members of the Democrat-led Congress held hearings along these lines, while Bush’s own party saw figures such as Pat Buchanan make hay out of the desire for a “peace dividend.” After all, the 1970s and 1980s were a point when worries over American decline and the concomitant rise of capable states such as Japan and reunified Germany were widespread. If ever a time seemed propitious for the United States to save money by cutting its overseas presence and letting other states bear the costs of providing security for themselves in a (much improved) international environment, this was it.

Bush, however, had none of it. As the confrontation with the Soviet Union ended, Bush and his team laid out the case for the United States to remain deeply involved abroad. Rather than deter the Soviet Union, American power would now be used to promote “stability” in Europe and Asia, resolve humanitarian problems, and prevent a regional hegemon from emerging in the Middle East (the latter also a high priority for Washington’s Cold War policy). In short order, policymakers began looking into expanding NATO, revitalizing the U.S.-Japanese alliance, and repackaging the U.S. military — much of which remained forward-deployed — for new missions such as peacekeeping and humanitarian intervention in regionally based conventional conflicts (e.g., Iraq). By the time Bush left office, calls for the United States to come home had not been ignored so much as sidestepped and overcome. As the 1992 presidential campaign itself showcased — with then-Gov. Bill Clinton castigating Bush for not doing more to engage Russia, promote human rights, and resolve humanitarian emergencies — Bush’s preference for a deeply engaged United States had become the new standard. The defense budget might fall, but America’s overseas involvement was a given.

Regardless of whether one thinks an engaged United States was the right course of action, Bush’s efforts to consolidate American involvement abroad after the Cold War was a radical break from American experience. Though pursued in understated form, Bush oversaw the first commitment of American power overseas in the absence of a pressing and obvious national security threat in the history of the republic. No longer would the United States pull back — as presidents as recent as Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower all believed prudent — when threats disappeared. Washington’s fear of entangling alliances was decisively defeated.

In doing so, Bush oversaw the most fundamental restructuring of American foreign relations since early in the postwar era. In his administration’s push to sustain American engagement into the post-Cold War era while protecting lodestones such as NATO that anchored this engagement, Bush laid the foundation for what would later develop into a highly activist American post-Cold War mission. Of course, Bush himself was far more cautious in exercising American power, famously refusing to drive to Baghdad in 1991 or to intervene in the former Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, the alliances, military, and diplomatic links that Bush protected at Cold War’s end created a strategic and political backdrop that later helped justify and abet America’s activist foreign policy. Using these tools, Bush’s successors had the wherewithal to take the United States into ethnic conflicts in Balkans and beyond, engage in the state-building efforts of Afghanistan and Iraq, and seek ways to simultaneously deter Russia and China as relations with those two countries soured.

Needless to say, had Bush not kept the United States involved abroad in during his presidency, America’s ability to throw its weight around on the world stage in the post-Cold War environment could well have been constrained. As importantly, some of the issues that came to dominate American foreign policy discussions over the last quarter century — issues such as NATO enlargement, deterring Iran and (previously) Iraq, and the merits of humanitarian action — would likely have never entered into the policy conversation

To be sure, Bush would almost certainly have recoiled at the radical label. As a member of the World War II generation, he saw his role as careful stewardship of the American ship of state. Radical transformations did not seem to be in the wheelhouse. Dramatic change, however, sometimes comes when it is least expected. So did it go on Bush’s watch. Confronting the end of the Cold War order, Bush transformed America’s mission from keeping major threats in check, to utilizing American power to resolve a host of ever-changing problematic issues du jure. Conservative though it may have been, Bush’s course was as dramatic a break from traditional U.S. foreign policy as any.

With his passing, it is thus worth remembering George H.W. Bush not only for his cautious statesmanship but — ironic for a man accused of lacking “the vision thing” — his radical vision for America’s role in the world.

Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson is an Assistant Professor of International Relations with the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University. His research focuses on U.S. foreign policy, grand strategy, and international security. The author of Rising Titans, Falling Giants (Cornell University Press, 2018), his worked has appeared in International Security, The Washington Quarterly, and other venues.

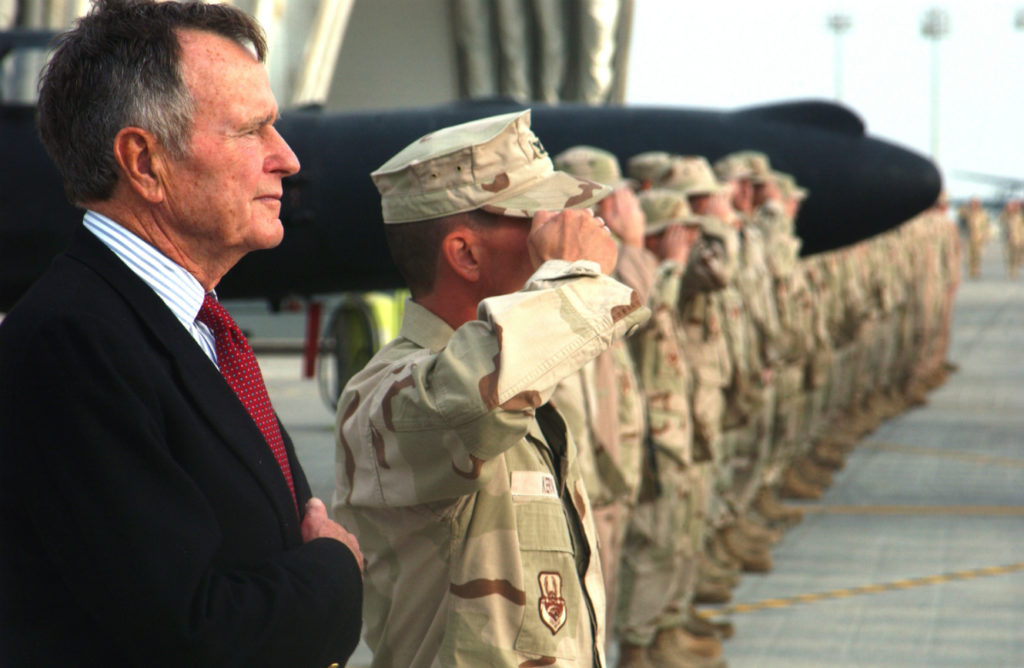

Image: (U.S. Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Jason Tudor)