OA-X Strikes Back: Eight Myths on Light Attack

In August, I was present at Holloman Air Force base, when the Air Force conducted a live-fly experiment with light attack aircraft. The first of its kind since the Vietnam era, the aptly named “Light Attack Experiment” brought together industry with Air Force operational and flight test crews to conduct an evaluation of non-developmental light attack aircraft. The objective was to assess the suitability these aircraft for traditional counterland missions such as close air support (CAS), armed reconnaissance, and combat search and rescue (CSAR). Predictably, there has been opposition to considering a light attack aircraft. While a comprehensive list of the misperceptions, conspiracy theories, and outright deceptions that populate some of these rebuttals would break the War on the Rocks word limit, here are a few of the most common myths.

Myth #1: Defended airspace is proliferating.

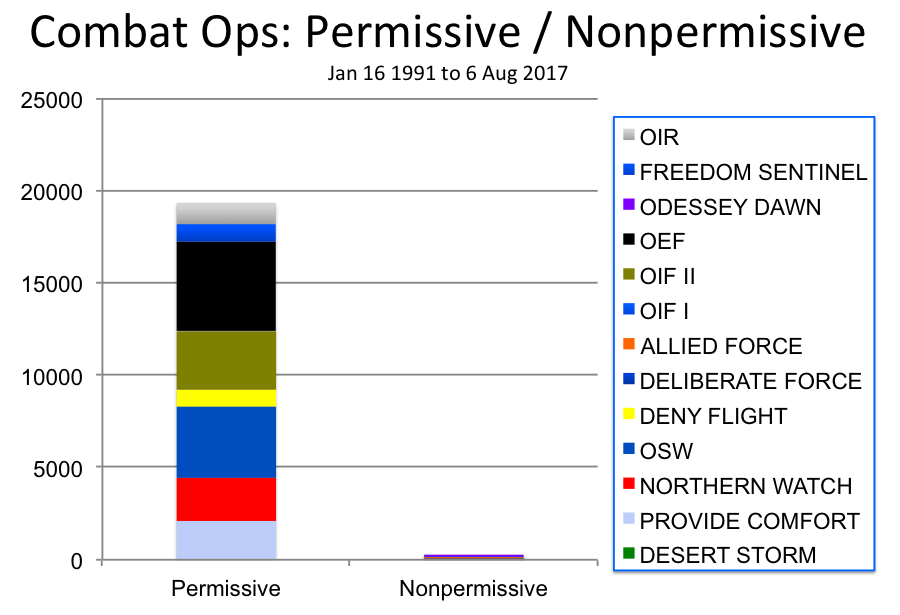

This particular fantasy has the massive proliferation of air defense systems expanding to cover the globe. Not really. If we were to compare the number of countries with substantial air defense capabilities now with those in 1988, the number would be about the same. Certainly, some nations have upgraded their air defense capabilities (Iran and Saudi Arabia) and some have maintained them; others have been unable to maintain the investment (Cuba and the United Kingdom) or seen it destroyed in combat (Iraq, Serbia, Libya, and Syria). In fact, we’re in a long-term steady state condition where the volume of defended airspace is static. Countries that have a longstanding investment in air defense do modernize, but advanced air defenses are expensive and specialized, making them useful for defensive purposes but little else. Certainly, there has been proliferation of small, shoulder-fired systems, but those systems are largely low-altitude systems historically most threatening to helicopters. The majority of airspace faced by U.S. aviators is undefended, or “permissive,” the vast majority of the time — as clearly evidenced by the lack of combat losses. As for that airspace that is defended, we need trained and ready forces to go there — forces that currently have been worn out flying in permissive airspace.

Myth #2: The aircraft is unsurvivable.

Clearly, an aircraft that isn’t a Fifth Generation aircraft is unsurvivable. There is something anti-magical about the OA-X class of airplanes in that they are commonly pitched as easy meat for anybody with an AK-47 or a 1970s-vintage, black market SA-7. Well, it turns out, they’re not. Last year the 81st Fighter Squadron’s A-29s participated in Green Flag in the Nevada desert. Playing part of “Red” air defense was a platoon of Marine Stinger operators — some of the best-trained operators in the world with the finest MANPAD ever built. The Marines were offered a weekend pass to anyone who got a valid shot on an A-29. No takers. The Afghan Air Force has been operating the A-29 Super Tucano in combat for 18 months; no losses. Colombia has operated the Super T for a decade against the FARC and ELN; likewise, no losses. But despite this hard data, and despite the fact that I have made detailed rebuttals of this proposition before, the OA-X is pitched as unsurvivable. No matter that it is hard to see, hard to hear, and can operate at altitudes well above 20,000 feet. No matter that the aircraft’s faint heat signature is dwarfed by any jet airplane. This proposition is subject to an easy test — when helicopters, drones and cargo planes can’t fly safely in that airspace, the OA-X probably doesn’t belong there either. But until then…

Myth #3: We don’t need it; lots of airplanes do what OA-X does.

Plenty of aircraft can handle ground attack. As it turns out, “plenty” is not nearly enough. The Air Force is below its minimum sustainable fleet size for combat aircraft, without even enough to absorb sufficient numbers of new pilots. But numbers aren’t the story — readiness is. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps fighters are suffering their lowest readiness rates since the 1970s, and with no other aircraft to utilize in the fight against violent extremists, we cannot climb back out of the readiness hole. With no relief pitcher, even the best hall of fame pitcher will run out of juice. If the airplanes and units are worn out because there is no relief, “plenty” is even less than you think it is.

Myth #4: We have other things to do with the money.

There are other priorities for a limited budget. Within current budgetary restrictions, this is true. The Air Force has too much mission and not enough money, and the best that Air Force leadership can do now is move holes around. Fill in one hole, make another. Sen. John McCain, a former attack pilot himself, recognizes this and marked up money in the 2018 NDAA — the down payment on a five-year funding profile outlined in Restoring American Power. This white paper postulated 300 light attack aircraft in six years. This is ambitious, but not impossible. The last military low-wing turboprop purchase was the T-6 program, which produced 292 aircraft in six years and kept going. Once the initial purchase is made, the investment starts to pay back: The turboprop light attack aircraft have a sustainment cost roughly a quarter of a legacy fighter, with a fuel consumption of only 5 to 10 percent of legacy jets. Not only is this a good use of taxpayer money, it’s a brilliant one with a substantial long-term payoff.

Myth #5: Jets “work better” than turboprops.

The poor turboprop just doesn’t get enough respect, and is often rejected because of its age, not its performance. If you want to fly high and fast, the jet is your baby. The propeller is speed-limited because the engine can only turn the prop so fast. But if you want to operate from forward bases on a logistical shoestring, think turboprop. Within its operating range (below about 400 knots), the turboprop is a much more efficient thrust-producer than the jet turbofan — more thrust with less fuel. The turboprops are highly resistant to foreign object damage, have long maintenance intervals, and are much, much cooler in the infrared spectra where heat-seeking missiles “see.” All of those reasons (except the last) are why you see mid-range airliners powered by turboprops. Amateurs study tactics, dilettantes study systems, but professionals study logistics — and the turboprop has a very low logistical burden compared to a jet.

Myth #6: The airplane is too slow.

Slow, of course, is automatically undesirable, or so the advocates of fast fighters would have you believe. It’s odd that this keeps coming around — it’s an argument that was made against the A-10 in the 1970s and has proven impossible to suppress. In Vietnam, the United States used both fast and slow Forward Air Control (FAC) aircraft for the mission of finding and directing tactical airpower against targets that were fleeting and flat-out difficult to find. Fast FACs were set aside after the war – what they made up for in airspeed didn’t offset the fact that they were not as good at finding fleeting targets. What we have decisively proven in test and in combat is that slow speed gets you two key benefits — more time to acquire small or hard to see targets, and the ability to operate under the weather. In the long battle to make the A-10 program successful, the YA-10 had to fly off against the high-speed A-7D Corsair II in 1974. The Hog’s relatively slow speed made operations under the weather feasible, and allowed attacks under lower ceilings and in worse visibility than the faster jet could handle. Plus, the A-10 could loiter for two hours, compared to the Corsair’s 11 minutes.

Myth #7: There is a secret plan to use OA-X to retire the A-10 and eliminate Close Air Support as an Air Force mission.

This is my favorite A-10 conspiracy theory. Having worked OA-X for nine years, I haven’t heard a whiff of this. A light attack aircraft will never replace the A-10 and isn’t intended to. The Air Force flew light attack aircraft in New Mexico, partnered with industry for an experiment. Interest is high. The VIP visitor list was packed like a Super Bowl. The Air Force is riddled with advocates for multirole aircraft that can do ground attack, and literally every officer involved in the writing of the OA-X enabling concept that started the light attack discussion is a combat veteran. Most of them were A-10 pilots. I can laugh this myth off; next week the guys in tinfoil hats will probably return to the news that NASA is hiring for a position to defend us against aliens. (Small ones, anyway.)

Myth #8: The struggle against violent extremists is winding down.

If the previous entry is my favorite A-10 conspiracy theory, this one is my favorite piece of pure wishful thinking. Anybody advancing this theory should hang up their defense analysis spurs and start hawking penny stocks. We tried this in 2011 (Iraq) and 2014 (Afghanistan) and it wasn’t true either time. Unfortunately, air operations to counter or contain violent extremists are past, present, and future, and may be the defining struggle of this generation. One author suggested that the Air Force just back off and supply less airpower, as if it was the USAF’s call to wind down and reduce airpower’s commitment. The last generational struggle, the First Cold War, lasted for almost half a century, from 1945-1990, and we’re really just getting started on this one.

This is the myth shortlist. There are more, and there will be more to come. In the light attack experiment we gathered hard data, which will set the record straight. The fundamentals on light attack are longstanding, well-supported, and fact-based. Light attack is an idea whose time has come — the question is not “should we” go ahead, but “can we”.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions and taking part in 2.5 SAM kills over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Col. Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of U.S. Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Air Force/Ethan Wagner