Of Hats, Jackets, and Turkish Politics

In an era of populism, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is at the helm. After coming to power as Turkey’s prime minister in 2003, Erdogan became president in 2014. In April, he won a referendum to become an executive-style president, simultaneously assuming the offices of head of state and head of government.

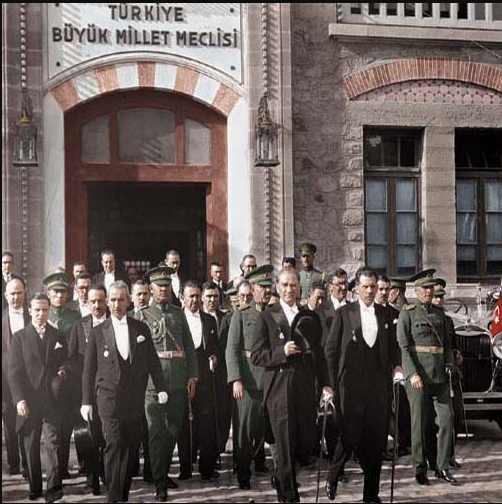

As one of us explains in The New Sultan, Erdogan has become the most unassailable Turkish politician since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk founded the Turkish Republic in his own image as a secular, Western, and European state. He had a strong military mandate which he used to carry out reforms to Europeanize Turkey. As Turkey’s simultaneous liberator, reformer, and founder, Ataturk has an inescapable pull over the Turkish citizenry, even over detractors such as Erdogan — a politician who was groomed in Turkey’s anti-secular political Islamist movement.

And after remaining in power for almost 15 years, Erdogan has consolidated enough control to rival the influence of Ataturk. Just as Ataturk used state resources, education, and public policy to shape Turkey in his secular image in the 1920s, Erdogan is now engaged in top-down social engineering to shape Turkey as its antithesis: a politically Islamist, socially conservative, and directionally Middle Eastern society.

Some of Ataturk’s reforms, such as the emancipation of women, were substantial and transformative. Others were superficial, aimed at making the Turks look European from the outside. For instance, the “Hat Reform” passed in 1925 outlawed the wearing of the traditional Ottoman fez and made it compulsory for all men to wear European-style hats. By rejecting the fez, Ataturk wanted to enact a sharp break with Turkey’s Ottoman and Middle Eastern past, symbolically and superficially pivoting the country towards Europe.

Overnight, elites around Ataturk complied with the law, donning Panama and bowler hats. Ataturk’s close associates quickly mimicked his personal style, and his cabinet transformed in accordance with his vision.

But in small towns of the Turkish hinterland, where no hat stores existed, frightened citizens donned paper-mâché hats to avoid persecution by the authorities. Although Turkish men did eventually adopt Western style hats, the process was long and arduous. This episode symbolized shortcomings in the “Ataturk model” of social engineering in Turkey.

Almost a century later, Erdogan governs a country that has progressed considerably, in large part due to Ataturk’s reforms. The literacy rate was 11 percent in the 1920s and is now at 97 percent. Proving how far Turkey has come, while Ataturk acquired power through military victory, Erdogan owes his position to a democratic mandate to govern.

But overlooking this progress, Erdogan has turned to “Ataturk model” — utilizing state resources to shape Turkey in his own image — though he, of course, does not share Ataturk’s values. Rolling back Ataturk’s gender advances, Erdogan’s has publicly declared that for “women and men to be equal goes against nature.” Even more alarmingly, his education ministry recently revised the school curriculum to exclude evolution and include jihad. And while Erdogan has not legislated anything similar to the Hat Reform, the gravitas of Turkey’s anti-Ataturk is making ripples across Turkish society.

Beginning with the presidential election of 2014, in which Erdogan became Turkey’s first popularly elected president, he has worn a blue tartan jacket to cast his ballot.

His jacket has gained enough attention to inspire hashtags and headlines: “Erdogan’s tartan jacket is on social media: It wins elections!” Fashion and body language experts have speculated that by preferring the blue tartan jacket to more formal wear, Erdogan declares to the masses, “I am one of you.”

And yet, this intended symbol of humility instead manifests Erdogan’s dominance: his closest associates in the Justice and Development Party — ranging from prime ministers to members of parliament — have all donned his suit, adopting Erdogan’s style just as Ataturk’s cabinet once adopted his. One of Turkey’s leading satirical websites even published a list of potential candidates for prime minister, all of whom shared one trait: having worn the blue tartan jacket.

When Erdogan became prime minister in 2003, he was the grassroots challenger to a state that was established top-down in the 1920s. But after remaining in power for a decade, Erdogan has become the top-down transformer himself. In Turkey’s populist brand of politics, access to political power necessitates fealty to Erdogan, and recently, that has meant dressing like the president.

Soner Cagaptay, the Beyer Family Fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute, is the author of The New Sultan: Erdogan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey. Oya Rose Aktas is the Yvonne Silverman Research Assistant at the Institute.

Image: T24