Navy and Marine Power from the Sea: The Nation’s “Perfect Blend”

On Veterans Day in 2011, President Obama attended the first-ever Aircraft Carrier Classic basketball game, pitting the then-number one ranked North Carolina Tar Heels against the Spartans of Michigan State. The contest was held on the deck of the USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70), the same warship that earlier on May 2nd had buried Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden at sea.

Just before tip-off, underscoring the Vinson’s role in the “critical mission to bring Osama bin Laden to justice”, Obama observed:

Every American citizen can make a solemn pledge today that they will find some opportunity to provide support to our troops, to those who are still active duty, to our national guard, to our reservists and to our veterans…It’s especially appropriate that we do it here.

Indeed, Vinson was a fitting backdrop for the 2011 ceremony and contest––a quiet reminder of the powerful strategic “stick” provided by America’s carrier fleet that provides sea-based aviation to help protect U.S. citizens, interests and friends worldwide. That force also packs a significant global combat punch.

Two years on, all defense programs are facing increased scrutiny and this focus has become even more intense, with the release last week of both the Fiscal Year 2015 Pentagon budget and the latest version of the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). Yet, despite the budget crunch, Pentagon leaders re-affirmed the strategic value and operational flexibility of the Nation’s fleet of carriers and large-deck amphibious ships. The QDR codified the need “to project military power over great distances” and highlighted the Department’s emphasis on using new combinations of naval platforms, aircraft and Marines to provide global commanders with more options. Fiscal pressures though have sparked discussions about future Navy force structure, including composition and numbers. Yet the decision to retire the carrier USS George Washington decades early, if sequestration is not rescinded by 2016, rather than fund its multi-billion dollar nuclear refueling, is energizing defense pundits to question once again the future of the nuclear-powered carrier force. This is extremely short-sighted.

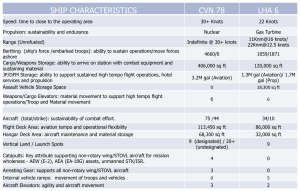

Some proposed “alternatives,” include buying more of the America-class (LHA-6) amphibious assault ships instead of next-generation CVNs. Doing so, they argue, would expand the strategic and tactical “reach” of sea-based air power by allowing more air-capable ships to be in more places around the world. But, this simplistic and ill-conceived notion flies in the face of real-world needs. In reality, the nation has much to gain from a “perfect blend” of air and ground power on and from the sea to carry out the full range of military operations.

Indeed, the need for flexible warfighting assets is becoming even more compelling and is shaping the need for a balanced fleet composed of both sea-based aviation and “boots-on-the-ground” power to meet the needs of regional combat commanders. While the Expeditionary Strike Group/Amphibious Assault Ship (ESG/LHA/LHD) solution is not the same as the Carrier Strike Group/Carrier (CSG/CVN) solution, both contribute greatly to the Navy’s overall capability portfolio to carry out warfighting strategies and operations. “The centerpieces of naval capability remain the Carrier Strike Group and Amphibious Ready Group,” current Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. Jonathan Greenert outlined in his 2012 Posture Statement.

Warfighting is First!

The Navy’s primary function is to conduct “…prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea.” Department of Defense (DoD) policy further requires the Navy to provide forces for sea control and power projection through sea-based global strike. For CNO Greenert, this translates into three primary tenets for the 21st century: warfighting is first; operate forward; and be ready. Thus, the Navy’s primary mission is warfighting. Should diplomacy or deterrence fail, the Navy must have the capabilities and capacities to defeat any adversary and defend the homeland and America’s allies and friends. As the CNO outlined in his Sailing Directions, the service’s number one responsibility is to “deter aggression and, if deterrence fails, to win our nation’s wars.”

DoD supports the CNO’s priorities. The 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance directed a rebalance toward the Asia/Pacific region while still emphasizing the critical Middle East area. With the “Asia pivot,” the U.S. military will have two “hubs” in the world for which to devise war plans and sustain operations: the Middle East to deter Iran, and the Asia-Pacific to deter North Korea and protect U.S. and regional partners’ interests in regard to a rapidly modernizing China. The “tyranny of distance” from Navy homeports to the hubs and the threats in those forward regions are fundamental elements driving required naval operational capabilities and capacities.

Sea-Based Air Missions

According to Greenert’s U.S. Navy Program Guide 2014, naval aviation is a critical component of the nation’s ability to carry out full-spectrum operations in the twenty-first century––from delivering humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR), to maritime security operations, and high intensity sea control and power projection in a major contingency. Helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft operating from nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, large-deck amphibious ships, cruisers and destroyers––complemented by all types of advanced unmanned aerial vehicles––are key contributors to the current and future capabilities of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.

The Navy’s nuclear carriers and large-deck, air-capable amphibious assault ships have fundamentally different missions, however, that drive significant differences in operational capabilities, air wing compositions and shipboard attributes. While there are obvious overlaps in mission requirements and capabilities––particularly in forward presence, crisis-response and HA/DR––interchanging missions and substituting CVNs for LHA/LHDs or vice versa could result in a risky mismatch between mission needs and capability. The result would be excess capabilities and capacities in one set of missions and insufficient capabilities and capacities in others.

The primary mission of the carrier is to serve as a sea-based platform to support and operate aircraft that conduct attack, early warning, surveillance and electronic warfare missions against seaborne, airborne and land-based targets. America’s carriers deploy throughout the world’s oceans in direct support of U.S. strategy and commitments. Additionally, CVNs play an increasingly important role as the Navy emphasizes forward operations in the world’s littorals, which assumes greater import as forward deployed, land-based forces are brought home after a decade of war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nuclear aircraft carriers allow the nation to project airpower worldwide, from the sea, without dependence on other government’s approval or access to local bases. In sum, the CVN can:

- Rapidly transit to operational areas at speeds in excess of 30 knots, which allows carriers to establish and maintain persistent forward presence and serve as a secure, mobile base for sustained operations––from diplomatic shows of force to high intensity combat

- Establish air and sea dominance, which includes suppression of enemy air defense, offensive/defensive counter-air, airborne early warning, anti-submarine warfare, and anti-surface warfare

- Conduct sustained airborne attacks on sea and land targets, operations that require time-sensitive targeting, battlefield air interdiction and close-air support

The primary mission of large-deck, air-capable amphibious assault ships, on the other hand, is to provide the Navy/Marine Corps team the means to carry out ship-to-objective-maneuver (STOM) tasks. Vertical-lift aircraft and landing craft help establish forward presence and power projection as an integral part of joint and multinational maritime expeditionary forces. As Marine Corps Commandant General James F. Amos explained in his 2012 Posture Statement:

Partnered with the United States Navy in a state of persistent forward presence aboard amphibious warships, your United States Navy and Marine Corps Team remains the most economical, agile and ready force immediately available to deter aggression and respond to crises. Such a flexible and multi-capable force that maintains high readiness levels can mitigate risk, satisfy the standing strategic need for crisis response and, when necessary, spearhead entry and access for the Joint Force. [emphasis his]

The Navy’s inventory of amphibious ships includes the USS Peleliu (LHA-5) and eight Wasp-class (LHD-1), large-deck, air-capable warships that carry out a wide range of expeditionary missions. These ships, equipped with aircraft, helicopters and surface-assault capabilities, rapidly close, decisively employ and sustain Marines from the sea.

Survivability is an important design aspect of our amphibious force, as a broad spectrum of anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) weapons are increasingly available to littoral countries worldwide––from naval mines to shore-based anti-ship missiles. The ability to “take hits” and keep on fighting is the hallmark of the Navy’s fleet design. The Navy has numerous intra-theater lift ships, but these ships are built to commercial shipbuilding standards and are not designed with features that enhance their survival in combat.

In short, while aircraft carriers and large-deck amphibs share some commonalities––e.g., they operate tactical aircraft from a sea base––they have fundamentally different missions resulting in significant differences in operational capabilities and characteristics. Indeed, the “main battery” of the large-deck amphibious ship is the embarked Marine force, usually a task-organized Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), with small detachments of short take-off/vertical landing (STOVL) fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters and MV-22 tilt rotors that support ship-to-shore and onshore maneuver operations. The carrier’s “main battery,” on the other hand, is the air wing comprising strike, fighter, close air support, electronic jamming and airborne early warning aircraft.

Comparing and Contrasting

Nuclear carriers and their air wings, comprising some 75 aircraft, represent a potent warfare capability that can quickly close to the operating area and provide robust, credible and sustainable combat power. Their design is optimized to support fixed-wing aircraft providing a broad spectrum of offensive-strike and defensive capabilities.

The large-deck LHA/LHD is the premier asset of America’s expeditionary forces. Its design is optimized for vertical-lift/STOVL aircraft and delivery of troops, equipment and material ashore. Since it can accommodate only vertical-lift/STOVL aircraft, it does not provide the breadth of defensive capabilities or the volume of offensive strike support available in a CVN. However, its vertical lift and large cargo capacity are ideally suited to peacetime HA/DR operations as well as sustained combat and maneuver ashore.

The nuclear carrier and large-deck amphibious designs are optimized for their respective missions and tasks, and each has demonstrated exceptional capability in these vital mission areas. Navy warfighting doctrine recognizes their differences and has always proposed the combined warfare capabilities of the CVN Carrier Strike Group (CSG) and the LHA/LHD Expeditionary Strike Group (ESG) together as an Expeditionary Strike Force (ESF) in those cases where major operations from the sea require the blend of military capabilities found in both. While each can approximate the other’s mission and tasks to a degree, overall effectiveness is reduced when they are arbitrarily shoe-horned into the other’s role.

Ford and America: “The Perfect Blend” for the 21st Century Navy

The Ford-class CVN-78 is the first new design carrier in almost 40 years. While nearly identical in size to the current Nimitz-class, Ford-class ships are designed with upgraded hull, mechanical, electrical and electronics capabilities. The Ford-class incorporates such advanced features as a new, more efficient nuclear propulsion plant, a revolutionary electro-magnetic aircraft launch system, advanced arresting gear, dual-band radar and a nearly three-fold increase in electrical generation capacity when compared to Nimitz-class carrier. These important technological improvements will increase operational efficiency and lead to significantly higher sortie generation rates. At the same time, maintenance and manpower requirements will be greatly reduced, allowing the Navy to reap more than $4 billion dollars in life-cycle savings per ship across its 50-year service life.

The America-class amphibious warships will provide forward presence and power projection capabilities as key elements of U.S. expeditionary strike groups. With elements of a Marine landing force, the lead LHA-6 and -7 warships will embark, deploy, land, control, support and operate helicopters. Future America-class warships will be fitted with well decks for landing craft and amphibious vehicles. They will also support contingency response, forcible entry and power projection operations as an integral element of joint maritime expeditionary forces. This ship will include enhancements––a gas turbine propulsion plant and all-electric auxiliaries––and a significant increase in aviation lift, sustainment and maintenance capabilities; space for a marine expeditionary unit, amphibious group or small-scale joint task force staff; an increase in service life allowances for new generation Marine Corps systems (e.g., MV-22 Osprey and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter); and substantial survivability upgrades.

America’s “perfect blend” of Navy and Marine power from the sea is a result of understanding their respective operational missions and the symbiotic relationship of CVNs and amphibious warships. Substituting one ship for the other breaks the logic of their inherent design attributes and compromises maritime power. Instead, the nation should stay the course with continued procurement of the “perfect blend” of power at sea. Together the Ford– and America-class warships, as the President recognized from the deck of the Carl Vinson, are a powerful “messenger of diplomacy and a protector of our security.”

Robert D. Holzer is senior national security manager with Gryphon Technologies LC, Washington, D.C., and previously worked for the OSD Office of Force Transformation. The opinions expressed here are his own.

Photo credit: Official U.S. Navy Imagery